Late Autumn: Ozu’s generational masterpiece.

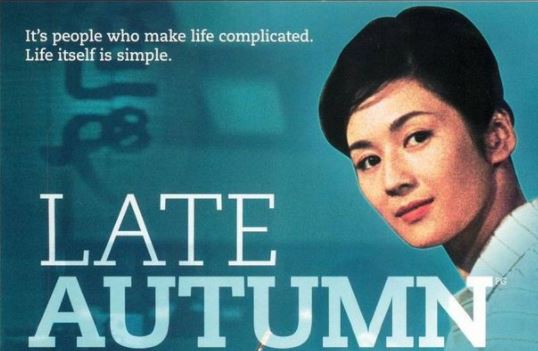

The third Yasujiro Ozu movie in our recent appreciation of Japanese Cinema is his 1960 masterpiece Late Autumn. It is a film which continues many of the themes of the previous two films I have covered in this series, Tokyo Story and The Brothers and Sisters of the Toda Family. The main difference is that Late Autumn approaches these themes with humour. Like Brothers and Sisters, it concerns a widow and her daughter – Akiko (Setsuko Hara) and Ayako (Yoko Tsukasa), only this time money is not an issue as both women work. On an anniversary of Akiko’s husband’s death his old college friends, Mamiya (Shin Saburi), Taguchi (Nobuo Nakamura) and Hirayama (Ryūji Kita), decide it is about time that Ayako, a beautiful 24 year old, marries.

Ayako however, does not want to marry as this would mean her mother would be alone so the three matchmakers set out to find a second husband for Akiko. The characters are all likeable and their motives, whilst sometimes foreign and antiquated, are clear and understandable. The numerous scenes involving the three friends are amusing and a joy to watch because their meddling is universal – older generations meddling with the affairs of the youth is a theme as old as time (Hollywood has made countless Jewish mother films over the decades).

The characters are also well drawn and each have a depth which is revealed as much in the performances as in the dialogue. Witness Hirayama’s preening when he is chosen to become Akiko’s new husband. This is matched with some real pathos, especially at the end of the film when Akiko must accept of her impending loneliness mirroring her character’s fate in Tokyo Story. The fact that Setsuko Hara was one of the true greats of acting is evident here, her eyes revealing the long road of loneliness and stoicism she had chosen to travel. In a glance we can see far into this character’s future.

Studying the generational differences in Japan through these films also reveals the birth of a modern era, of a Japan that took the influences of the West and used them to build upon the traditions of the East. There is great affection and no animosity between the generations yet their approaches and their expectations differ greatly. The old men still believe that marriages should be arranged whilst the youngsters believe that they should be able to decide for themselves, yet there is still a residual trace of tradition in the younger generation and when a suitor is found Ayako does agree to meet him.

This is in complete contrast to Yuriko, Ayako’s best friend, who is happy to confront the old men, exposing the silliness and the thoughtlessness of their plans. The men are suitably chastised and end up respecting Yuriko who they join for a night out. This is something of a paradox, the men seem to believe they have the right to arrange a union behind the women’s backs yet they are also very happy to accept a woman in her early twenties as an equal.

Late Autumn is told, as with all Ozu movies, in the minutiae of everyday life, over food and (lots) of drink, at home, in offices and during break time and perhaps the biggest event of the movie – Ayako’s eventual wedding – is pushed into the background. As Tarantino chose not to show the robbery in Reservoir Dogs, Ozu does the same with this pivotal moment in these people’s lives.

Sometimes it is easy to determine which film in a director’s filmography is the best, perhaps one film stands out more than any other, but there are many filmmakers for whom this is very difficult indeed. This is the case with Yasujiro Ozu. Undoubtedly his most famous film is Tokyo Story and it is perhaps his most accessible film. It is a beautifully told story that does not put a foot wrong throughout. The same can be said of Late Autumn, a film I have seen numerous times now and it never fails to give me a smile. The reason it works is because, and I have said this a number of times in my previous Ozu retrospectives, it is a very human story. This is what an Ozu movie is. It is a stylistic filmic experience without ever being flashy. It is a mannered study of themes whilst remaining very human. It presents a place and a time very different to our own experiences whilst remaining completely accessible.

I can understand if the films of Yasujiro Ozu are not to everyone’s tastes in the 21st century. We want our stories to be to be told in a quick, almost snappy manner. We don’t have time to let the story develop, to peer into the lives of others, of other cultures and wait for the story to unfold. Yet these films draw you in if you give them a chance. I resisted for many years before I finally watched Tokyo Story because I thought the praise of arthouse critics just masked an inaccessibility that I would struggle with, yet, when I finally watched it I was moved, profoundly so. There is a beauty in the films of Ozu that I now find impossible to resist and I am so glad I gave in and watched them.

Roger Ebert once gave a Ozu a most wonderful eulogy, “To love movies you simply must love Yasujiro Ozu.”