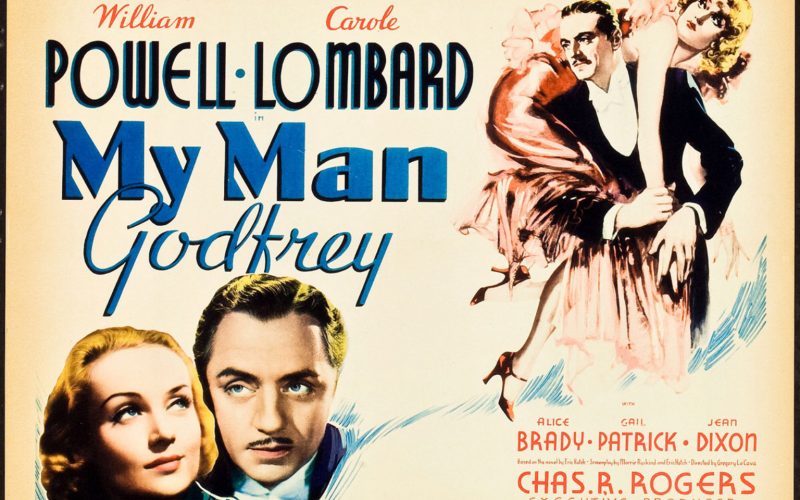

My Man Godfrey (1936).

My Man Godfrey is a 1936 screwball comedy in which the plot twists and swirls in a way that only 1930s Hollywood screwball comedies could. It starts simply – Wiliam Powell plays Godfrey Smith, a down-and-out living in a shack next to a city dump. The living area, if it can be called that, is getting smaller every day as the dump trucks continually dump the city’s refuse closer and closer to the shacks. The inhabitants are the good sort. They may have fallen on hard luck, but they are the salt of the earth in the same way as the working, or non-working, men are in Sullivan’s Travels or Miracle In Milan.

One evening, Godfrey is accosted by a couple of high society girls who are looking for a ‘forgotten man’. They don’t want to help this man, whoever he may be, they just want him so they can score points in a scavenger hunt.

The two women – sisters Irene and Cornelia Bullock – are rather blunt and rude about the whole thing and Godfrey ends up pushing Cornelia into the trash. However, after speaking to Irene, he agrees to allow her to take him to the party so that she can score the points she requires to win the hunt. He goes because he wants to help the young woman and because he wants to tell everyone at the party of his disgust at the way they are treating men who have lost just about everything. To the rich of the city of Gotham, the poor are hardly worth thinking about beyond mere entertainment.

What he doesn’t anticipate however, is that Irene does feel sorry for him and offers him a job. Her family needs a butler and he would be perfect. This in itself would be perfect Screwball fodder, however, something more is required – a love affair. Soon we discover that Irene has fallen for Godfrey and is continuous upset by his reluctance to return the feelings.

Godfrey ends up being the perfect butler, calmly going about his business despite the peculiarities and eccentricities of the family. Why is he so suited for this role? That’s another of those screwball twists.

The family is led by the wonderfully reliable Eugene Pallette as Alexander Bullock. A favourite character actor of mine, Pallette’s tense and forced delivery rings just the right note as the pragmatic father who is indulgent to the extreme, whilst also being fearful of the future. He may complain about money and his family’s behaviour, but he just can’t seem to control them. Given the eccentricities of the family, Bullock is the anchor that stops them from drifting too far from reality.

Pallette was one of those actors that any lover of classic Hollywood would know, even if they couldn’t put a name to his face. He was Friar Tuck in the 1938 Errol Flynn classic, The Adventures of Robin Hood, he starred with Tyrone Powell and Basil Rathbone in The Mark of Zorro (1940), he was one of the backroom conspirators in Mr Smith Goes to Washington (1939). He was also be seen in Pin-Up Girl (1944) with Betty Gable, in Ernst Lubitsch’s Heaven Can Wait (1943), and opposite Marlene Dietrich as the gambler Sam Salt in Shanghai Express (1932). A wonderful actor whose delivery brought distinction and humour to every character he performed.

His wife, the ditzy and flighty Angelica Bullock (Alice Brady) has taken on a very odd protege Carlo (Mischa Auer), a man of questionable talent but unquestionable appetite. Angelica exists in that wonderful twilight zone in which money grows on trees and is something you should never worry about.

Both daughters are spoilt and they manifest this in two very different ways. Cornelia is rude and underhanded, and is willing to go to any length to get what she wants, not caring who she hurts along the way. She was played by Gail Patrick, an accomplished actress who, when her acting career, which included films such as the original Brewster’s Millions (1935) and My Favourite Wife (1940), ended, went on to executive produce Perry Mason (1957-66 & 1973-74) as well as serving as vice president of the National Academy of Television Arts and Sciences.

The star of the film however, is the effervescent Carole Lombard as Irene. Lombard was a truly wonderful comedienne who could get a laugh simply by raising her eyebrows and muttering ‘Hmm?’ – just watch her in Lubitsch’s To Be Or Not To Be (1942).

Here she plays a role that could easily have been grating as the lovelorn younger sister who is constantly breaking down in tears whenever anyone (usually Cornelia) mentions Godfrey. Yet by the end of the film I couldn’t help but fall in love with her. It’s so sad that, within six years of the release of My Man Godfrey, Lombard would die in a plane crash alongside her mother as she travelled across the United States trying to raise money for War Bonds.

Godfrey himself is perfectly played by Lombard’s ex-husband William Powell (they had divorced in 1933). He plays the role with such patience and dignity, without ever seeming remote. He can be charming and intelligent without ever being condescending, unless he wants to be of course.

At the start of the film I was worried that I wouldn’t like the characters enough to want to spend 90 minutes in their company. Like Renoir’s The Rules Of The Game (1939), this is a film about shallow and sometimes empty people too caught up in their petty lives to care for anyone else. Yet by the end, I ended up liking them: their love for life, their passions and their personalities were attractive even though they barely exist in anything resembling the real world. Each character is distinct, and each performance is perfectly weighted, balancing nicely between the obnoxiousness of wealth and a human side that’s only revealed once we get to know them.

Director Gregory La Cava keeps the pace up so there is not a moment when the film lulls. This is not Howard Hawks fast, but there isn’t a single moment that drags or even alters pace. Cinematographer Ted Tetzlaff gives the film a beautiful lush quality that Hollywood in the ‘30s excelled at. The script by Morrie Ryskind and Eric Hatch (based on Hatch’s novel) zings along nicely and has more than its fair share of great one-liners:

“Money, money, money! The Frankenstein monster that destroys souls!”

“I don’t mind giving the government 60% of what I make. But I can’t do it when my family spends 50%!”

This could easily have been as vacuous and sterile as Pretty Woman, which was released 54 years later and shares a similar premise, but luckily this has a very uplifting, although never preachy message beyond just the fairy tale of true love. This message, regarding the dignity of those men who are unable to find work, is like that of Sullivan’s Travels, and My Man Godfrey could easily have been one of the uplifting films that the studio executives were begging John L. Sullivan (Joel McCrea) to make in that film.

By the time the film ends, with perhaps the best one-liner of the entire movie, I had a broad smile on my face and a lightness in my heart. It made me feel good and that’s the best compliment you can make of a film like this. I wasn’t challenged and I didn’t have to ruminate at length about the meaning of the film, as it was clear and concisely achieved. Some films are meant to get you in the heart, others in the brain and others still in the funny bone.

My Man Godfrey had one purpose, to lift the mood of its viewers, and it did it wonderfully. It made me feel good and there’s nothing more to say.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 9/10