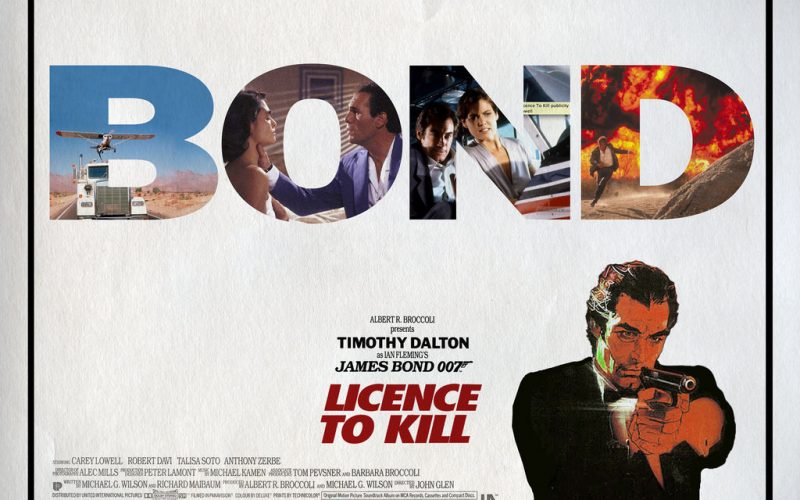

Licence to Kill (1989).

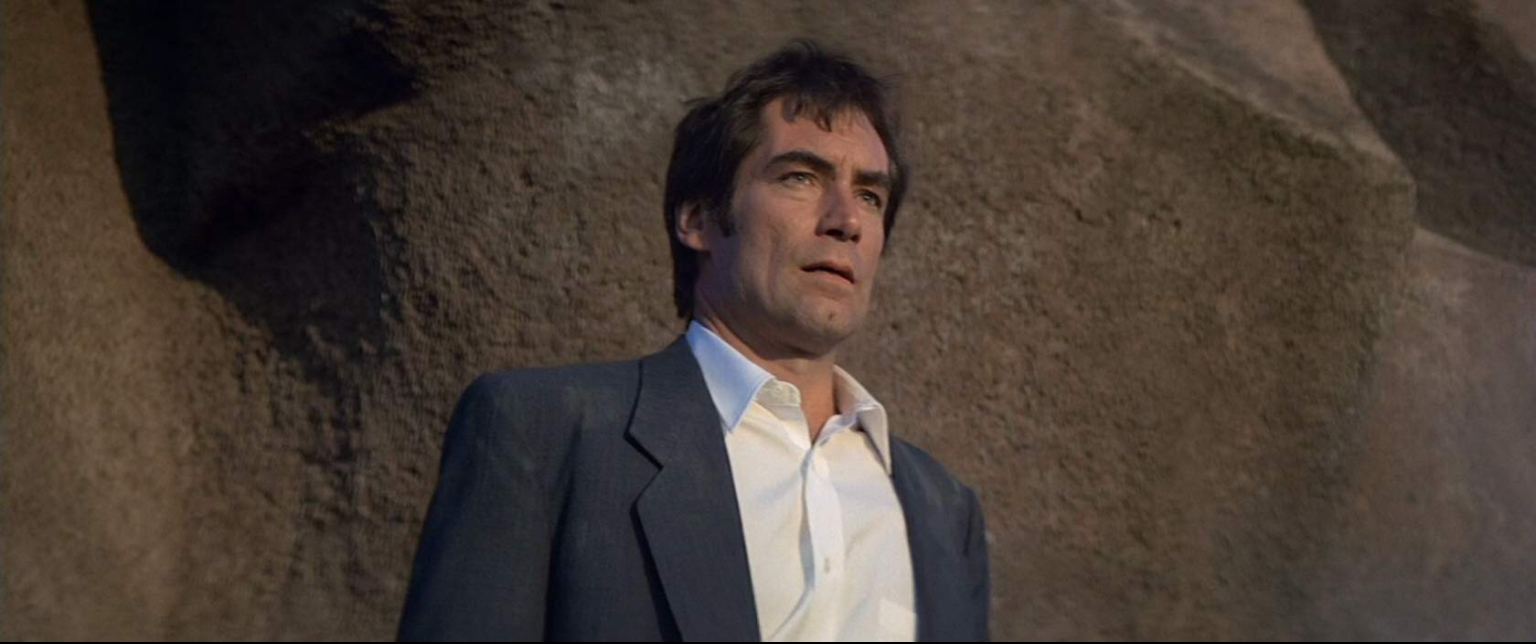

With Roger Moore hanging up His tuxedo after 1985’s A View To A Kill, the role of the world’s favourite Super Spy, James Bond was passed on to a relatively lesser known actor (at that particular time at least), Timothy Dalton with the release of 1987’s The Living Daylights. Dalton had mainly been known as a stage actor prior to his new appointment and had toured with the Royal Shakespeare Company, although he had already appeared in several motion pictures and was probably most recognisable for his role as Prince Barin in 1980’s Flash Gordon.

The role of Bond wasn’t that unfamiliar to him as he’d initially been in serious consideration to precede Moore in the first place, when he was first courted to replace Sean Connery in 1969’s On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, but in a 1987 interview he explained that he’d turned down any idea of playing the role that would eventually go to Australian George Lazenby, due to his relatively young age at the time;

“Originally I did not want to take over from Sean Connery. He was far too good, he was wonderful. I was about 24 or 25, which is too young. But when you’ve seen Bond from the beginning, you don’t take over from Sean Connery.”

Dalton was once again in serious contention for the part when the film’s producers skirted with the idea of changing the lead actor in the early ‘80s, but ultimately it appeared that his eventual predecessor, Pierce Bronson, was the favourite to nab the part after Moore’s departure, only for the GoldenEye star to fall foul of the legal red tape that bound him to his television show Remington Steele. With the Broccoli’s first choice now benched you can almost picture them finding an old headshot of Dalton and wondering if it would be third time lucky if they asked him again.

Dalton of course accepted their proposal this time around and the rest is now cinematic history. A fan of the original Ian Fleming books, he agreed to a three film deal on the proviso that his Bond would be a harder edged version of the character than audiences had become accustomed to during Moore’s reign.

Dalton’s opening gambit in 1987’s The Living Daylights proved successful both critically and financially with the film outperforming Moore’s last two Bond films 1983’s Octopussy and 1985’s A View To A Kill, with a worldwide box office gross of $191 million to make it (at that time) the fourth most successful film in the Bond franchise.

It appeared that filmgoers approved of this darker version of 007 and for Dalton’s second appearance as James Bond, the producers took an even bolder step with 1989’s Licence Revoked, or as it would end up being known after a last minute title reshuffle, Licence To Kill.

This came after American test audiences remarked that the original title reminded them of having their driving licences taken away.

Licence To Kill was first Bond film to earn a 15 certificate in the UK, although it did scrape through with a PG-13 rating in the US. Whereas The Living Daylights had given audiences an introductory glimpse at a harder, grittier Bond, the second and unfortunately, last appearance of Dalton’s 007 really upped the ante. This new incarnation of Bond really was a more serious take on the character.

Hitting just the right mix of the old and the new would be a challenge for sure. One of the most memorable aspects of any Bond film is the score. With John Barry passing on his regular duties due to having had throat surgery, the producers decided to go with a completely new feel by giving composer Michael Kamen the job. Kamen had scored 1987’s Lethal Weapon and 1988’s Die Hard. It would be fair to say that the score he produced for Licence to Kill is very similar to his scores for those two previous films, but it definitely adds to the whole experience that you are indeed watching a different kind of Bond film.

Initially Eric Clapton and Vic Flick were asked to write and perform the title song. The theme was said to have been a new version based on the original Bond theme but when this failed to come to fruition, the filmmakers went with the more traditional Bond opening theme titled “Licence to Kill” which was written by Narada Michael Walden, Jeffrey Cohen and Walter Afanasieff, and was based on the horn line from Goldfinger, which meant it required royalty payments to the original writers.

The title song was performed by Gladys Knight and the accompanying music video was directed by Daniel Kleinman, who would later take over the reins of title designer from Maurice Binder for the next Bond film, 1995’s GoldenEye.

This 16th film in the series was the first not to utilise a title from the Fleming books, although the plot is loosely based around two of the author’s short stories. The film would also be the fifth and final film in the consecutive run of Bond films for director John Glen. The established director was now faced with the considerable task of bringing a new take on the established character, whilst still keeping elements of the old standard that were so well known to its audience. This is perhaps highlighted perfectly in the opening scenes where Bond is seen alongside his old friend, CIA agent Felix Leiter and Leiter’s old pal Sharky, on their way to Leiter’s wedding in the Florida Keys when their wedding car is flagged down by DEA agents asking Leiter to help them assist in capturing drug lord Franz Sanchez, the very man Leiter has been chasing for years.

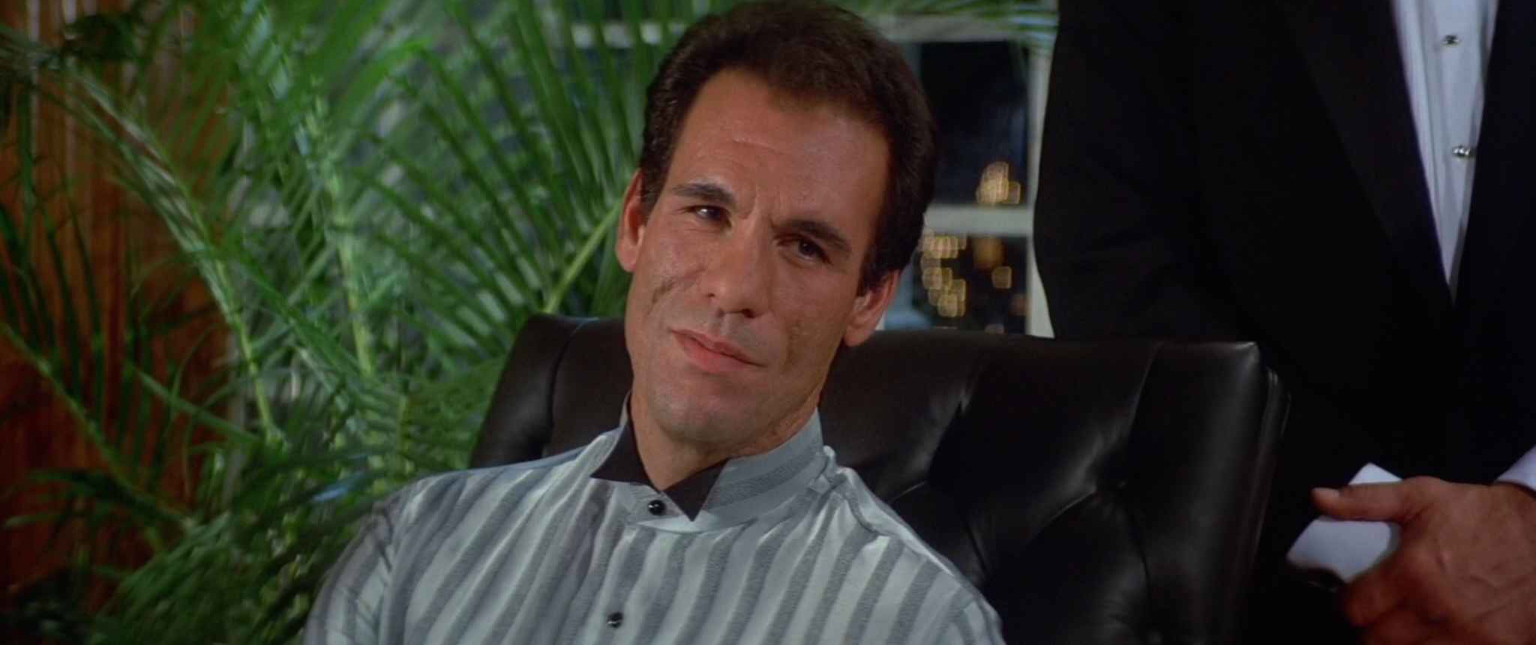

Bond of course comes along for the ride, as any Best Man would do to make sure that his friend still makes it to the church on time. At this point we are first introduced to new style of Bond Villain in the form of Franz Sanchez, played with suitable evil intent by Robert Davi. A man not interested in taking over the world in the traditional Bond Villain sense, he simply wants to become the world’s richest and most successful drug dealer and has the secret to a revolutionary new way of smuggling cocaine in a liquid form, disguised as gasoline. He is most definitely not the type of villain that we are used to in the series with their typically far-fetched megalomaniacal plans of world domination. Sanchez is far more likely to kill you in cold blood than leave you covered in liquid gold.

The capture of Sanchez is perhaps the first indication of the mixed identity this film will present throughout as it tries so hard not to be a traditional Bond film but ends up falling back into realms of familiarity. With Sanchez seemingly evading capture in his small light aircraft, Bond and Leiter give chase in the DEA’s helicopter so that Bond can then dive out and loop the craft’s pulley winch around the tail of the plane. With Sanchez literally hooked up and captured, both Bond and Leiter proceed to then skydive right down into Leiter’s wedding ceremony, entering the chapel with the parachutes dragging behind them like a pair of makeshift wedding trains.

“Maybe this is a traditional camp Bond film after all?” you may ask yourself. Well no, because the next major scene involves Sanchez’s henchmen waiting for Leiter and his new bride in their honeymoon suite. With Sanchez using a crooked DEA agent to help him escape custody, the drug dealer is out for revenge and exacts his wrath by feeding (apparently) Leiter to a hungry shark! Prior to Leiter’s demise he asks if his wife is ok, only for Sanchez’s lead heavy Dario (played by a very young Benicio del Toro) to playfully inform him that he gave her a suitably robust honeymoon night prior to killing her.

“Oh we made sure that she had a gooood honeymoon!”

Felix Leiter has been played by a number of actors over the years but this incarnation played by David Hedison had been seen opposite Moore’s Bond in 1973’s Live & Let Die, so it was perhaps an added bit of gravitas when he is seen being fed to the (plastic looking) shark.

The next day Bond stumbles onto the story of Sanchez’s escape and rushes to Leiter’s home to find his best friend laying maimed on the sofa (surely he would have died of blood loss by now) and his new bride murdered in the bedroom, although she is still strangely fully clothed and has no visible injuries? This scene in itself is perhaps telling of how nervous the filmmakers were about pushing the envelope too far. Sure they wanted a harder edge to the film, but not one that was too hard.

With a mind focused on revenge, Bond sets off to track down Sanchez, initially helped by Leiter’s friend (who is ironically called Sharky!) Throughout his subsequent investigations, Bond is able to locate where his friend was brutally tortured and also happens to stumble upon the shamed DEA agent who helped Sanchez escape. Bond exacts his revenge by feeding the agent to the very same Tiger shark without hesitation, displaying the cold hearted killer that Dalton had been dying to portray.

We next see Bond come into contact with his MI6 boss ‘M’ played once more by Robert Brown. This scene again depicts the difference in tone this film was aiming for. Instead of the playful verbal sparring that we were previously accustomed to seeing between the two men, here they enter into a far more tense verbal standoff with Bond refusing to stand down, leaving M to inform him that his license to kill is now revoked, and with that Bond spots a sniper in a nearby tower, leaving him no option but to leap from a balcony to evade a more permanent form of retirement.

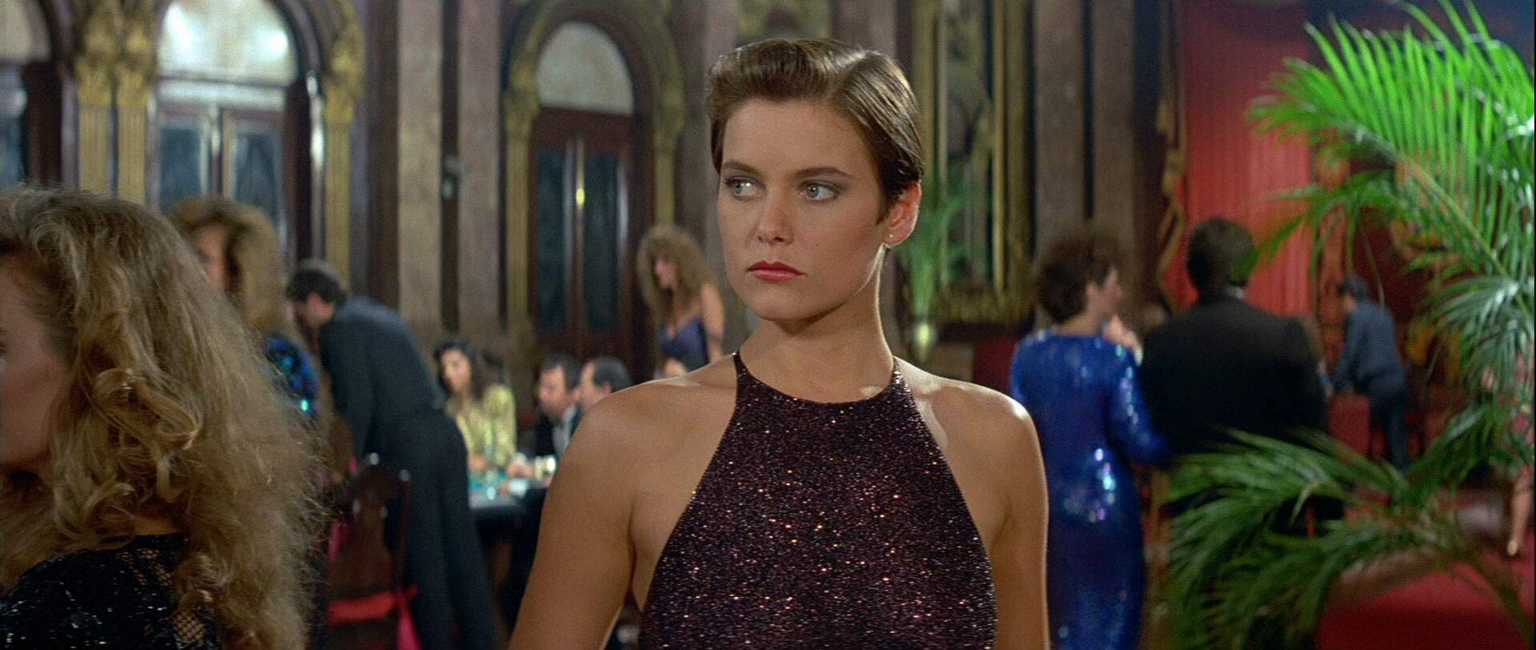

As Bond runs away, a fellow agent draws his weapon to shoot the fleeing spy only for M to stop him, not because he wants Bond to survive, but rather that there are too many potential witnesses nearby! Bond is now completely rogue and his continued pursuit of Sanchez leads him to teaming up with ex-CIA agent Pam Bouvier (Carey Lowell) who just happens to be a tall, beautiful woman (because it is still a Bond film after all), and the two follow Sanchez down to his base of operations which is located in the fictional Republic of Isthmus in an unspecified region of the Central Americas. Here Sanchez is laundering his drug money thanks to a corrupt dictator via a casino and bizarrely a religious evangelical preacher named Joe Butcher (Wayne Newton). Bond uses his considerable talents to full effect in the casino to win big and get to finally meet Sanchez where he proposes he work for him as an assassin for hire in an attempt to get close to the drug dealer’s corporation. Bond does not to simply want to kill the drug lord but also ensure that his entire empire is destroyed in the process. He is no longer happy to simply chop the head off the snake, he wants to destroy the carcass as well.

Once he is in place, Bond is joined by his old stalwart ‘Q’ played by the man who truly defined the character, Desmond Llewelyn. Although again, this could be seen as a return to form for the film, what with the gadgets he brings along to assist the spy, explosive toothpaste anyone? It does lend somewhat to the new tone that the film is aiming for. Q himself has gone rogue, using his “vacation time” to help out his old friend. Again this leads us to believe that we may just have a breakout Bond film here, especially when Sanchez finally discovers Bond’s true identity and asks of his true motivations, leaving him to seemingly plunge into a huge industrial grinder, whilst casually remarking through a sneer to the spy,

“When you’re up to your ankles, you’re going to beg to tell me everything. When you’re up to your knees, you’ll kiss my ass to kill you.”

But yet again as quickly as you are fooled into thinking that this film has broken the chains of Bond’s past completely, we are quickly yanked back into the familiar. Sanchez escapes from his underground lair (sigh) in a convoy of fuel tankers containing his liquidised narcotics and Bond gives chase in another truck, leading to a chase scene that’s very much “Classic Bond”.

Bond somehow manages not only to perform wheelies with the truck crashing through a wall of flames on only its rear wheelbase, but also flipping the extremely large vehicle onto its two side wheels to evade an incoming missile! But, just when you think the film has finally settled upon using its old blueprint, we are dealt yet another sucker punch. The chase leads to Bond and Sanchez fighting upon the top of a moving fuel tanker and whilst it’s not exactly akin to the now familiar Bourne-type of rumble, it is several steps ahead of the judo chops of the Moore era.

Dalton, whilst not a muscle bound Action Hero type, is a man of considerable stature and is able to use his 6 foot 2inch frame to effectively display aggression on screen. From the opening scene of this film’s predecessor, we get to see that Dalton’s Bond is not afraid to fight dirty. His use of head butts had an immediate impact upon this writer in his younger years and made me sit up and take notice of this new, darker Bond. Sanchez more than holds his own against Bond and his choice of a machete as a weapon over some more bizarre gadget such as steel teeth, perfectly encapsulates the feel that this film so desperately craves.

The fight is brief but suitably brutal and is then brought to a conclusion when then trailer careens off a hillside, flinging the two men towards the ground amidst the wreckage. To this day the sight of a bloody and injured Bond crawling along the desert ground, gasping for air still shakes me somewhat. Although it’s far more prevalent in the new Daniel Craig era to show more of Bond in realistic situations, this, at the time, was akin to seeing Christopher Reeves’s Superman losing his powers in Superman II. As Bond collapses in front of Sanchez and his death from the machete blade appears imminent, Bond is quick to show his would be killer the reason for all that has happened as he produces the engraved cigarette lighter that was given to him as a wedding present by his friend and then knowing that Sanchez will be doused in spilt gasoline, sets fire to him. No trademark quip is needed from Bond in this scene. It’s an eye for eye, pure and simple.

Whilst Licence To Kill failed to beat The Living Daylights at the box office it still did well worldwide and managed to pull in a respectable haul of $156 million, which when coupled with the fact that it had a more restricted audience due to the more mature rating and possibly due to it being the first film in the series of a “New Bond” naturally gathers more widespread interest from the casual film fans, speaks volumes for the film.

The US box office returns were also significantly affected by the film being released in direct competition with the third Indiana Jones film which just so happened to introduce a new character played by a none other than Sean Connery, echoing Dalton’s previous fear of being compared to the original big screen version of the character.

Licence to Kill would be Dalton’s last hurrah as the debonair super spy. With one film still on his contract to be completed the actor found himself sat on the sidelines and unable to complete his trilogy as a result of a lengthy legal dispute between MGM/United Artists and Eon productions, which lasted for four years until 1993. By now Dalton’s contract had expired due to the specific timescales given for the scheduled filming of his three films and he shocked everyone when he refused to return to the role after preliminary negotiations, with an official announcement citing that after the long, drawn out disputes he’d simply lost the urge to return. The announcement of Pierce Brosnan as the new Bond followed shortly afterwards and GoldenEye was released in 1995.

Licence To Kill may well be one of the most important Bond films in some respects. It showed that there was indeed a market for a more serious and stripped back version of 007. Of course, as I’ve previously alluded to throughout this piece, the film does tend to merely flirt with the idea rather than giving it a full commitment, but as much as the Daniel Craig era brought the character into a more realistic setting, this film surely laid down the foundations many years before Casino Royale showed us a grittier, more realistic Bond than we’d seen before.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 007/10

Licence to Kill Quad poster by Owain Wilson.