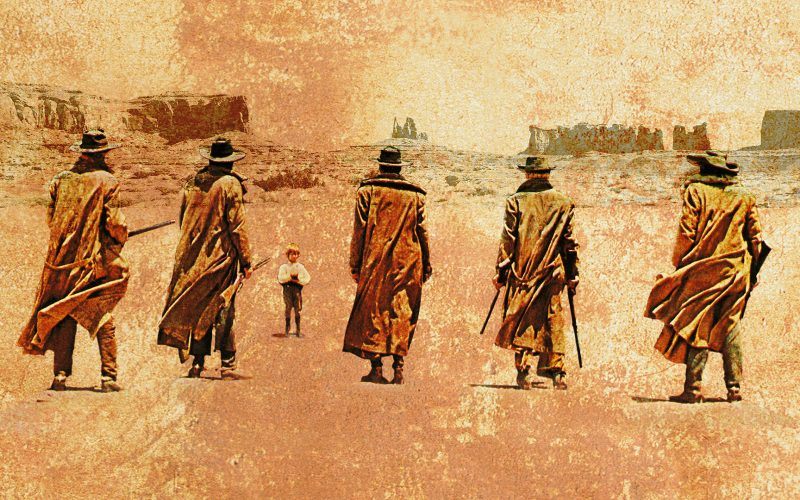

Once Upon A Time In The West (1968).

The western, a genre has gone through a multitude of changes over the last century. It has evolved as a genre, creating tropes – visual, verbal and musical; then devolved as it was broken down and put together again to reflect a change in society, only to be revised and reinvented in recent decades.

Whereas John Ford is arguably the man who helped define the Western from its earliest form with films like The Iron Horse (1924) and Stagecoach (1939] to later classics like The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962) and The Searchers (which is reviewed here), the man who probably played the biggest role in its reinvention was Sergio Leone.

Somewhat ironically, Leone’s career began in Italy when the Italian film industry was trying to reinvent itself. In 1963 the film industry was rocked by the colossal failure of the historical epic Cleopatra which shook the movie world to its very core. Up to this point Leone had made a living working as an assistant director for both local productions and Hollywood blockbusters including Quo Vadis (1951) and Ben-Hur (1959) (he had even claimed to have directed the famous chariot race but, while he worked on it, he certainly wasn’t the director).

Leone also directed a small number of films, beginning with The Last Days of Pompeii (1959) when its director, Mario Bonnard, fell ill during production, and The Colossus of Rhodes (1961) which was his debut as director. He first made an impact, however, with Fistful of Dollars (1964) the remake of Akira Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961) featuring Clint Eastwood as the iconic Man with No Name, Fistful of Dollars was a huge international hit and presented the western in a way that had never been seen before. Gone were the distinctly American ideals of individualism and the American Dream, and instead Leone gave us a cynicism that at times bordered on nihilistic.

Soon after Leone completed the trilogy with For A Few Dollars More (1965) and The Good, The Bad and The Ugly (1966), setting a standard which few filmmakers had ever (or since) matched.

Hollywood soon took notice of Leone’s work and offered him massively increased budgets and opportunities but the one thing he wanted more than anything they wouldn’t give him. For his first American film he wanted to make his epic Once Upon A Time in America, a look at the development of the US in the twentieth century focusing on gangsters.

Unfortunately for Leone’s aspirations at the time, Hollywood wanted more of the same from him. He’d made his name making westerns, and they wanted to bet on a sure thing so Leone had to go back to the drawing board and come up with another idea.

Leone had always been open about his love of the genre and particularly the films of John Ford. On a trip to Monument Valley he once astounded his fellow travelers by pointing out the various shots and backgrounds that Ford had used in this beautiful part of Arizona. He could name the films and the scenes as well as the angles that were used.

The idea for Once Upon A Time In The West came from discussions with future directors Dario Argento and Bernardo Bertolucci who wrote the story which screenwriter Sergio Donati along with Leone adapted into a screenplay. The story of how Bertolucci and Leone fist met is both amusing and probably gives an insight into the maestro’s mindset. After the premier of The Good, The Bad and The Ugly, the two men met and Bertolucci told Leone that he was a huge fan.

‘Why?’ Asked Leone.

Bertolucci gave a pretty standard answer about how his films were amazing etc.

‘Why?’ Asked Leone again.

Bertolucci has admitted that he was getting irritated by this line of questioning, thinking that Leone was only fishing for compliments. In the end he said:

‘I love the way you film the horse’s ass!’

Leone was confused and asked him to elaborate.

‘Most filmmakers,’ Bertolucci explained, ‘filmed a horse from the front or the side, which is effective but you often film them from behind so you can see the muscles working on these beautiful and fabulous animals.’

Leone was impressed and amused and a friendship was born.

Although Leone loved the genre and, with Bertolucci and Argento, spent much of the next year watching and rewatching the classics, he didn’t like the themes and the principles that they often stood for. The American Dream was not the Italian reality. He had revealed as much in his previous films, but this time he wanted to deconstruct the very making of America.

One film that had a huge impact on him was Ford’s The Iron Horse, a 1924 silent epic which chronicles the creation of the transcontinental railroad. It‘s a film which celebrates the drive and idealism of the early pioneers and is well worth checking out by fans of the genre. Leone’s cynicism wiped away the noble aspirations of Ford’s film and instead looked at the underbelly of the period, much in the same way David Lynch would peel away the layers of societal civility in Blue Velvet decades later.

Once Upon A Time In The West begins with one of the all-time greatest opening sequences. A ten minute symphony of sounds as three men converge on a station and wait for the train to arrive. These three men – Stony (Woody Strode), Snaky (Jack Elam), and Knuckles (Al Mulock) – are awaiting for the arrival of one man. They don’t know his name or the reason for his visit. They only know that he wants to see their boss, Frank, who has no intention of keeping the appointment. The appearance of Woody Strode (who had appeared in such classics as The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and Two Rode Together) immediately reminds us of John Ford and the classic western,

This is the first instance of Leone undermining the classics. Strode, along with his two compatriots, are there for one reason – murder. Cold blooded assassination. It’s a sequence that seems to be devoid of music but in fact, the ambient sounds of the station – the creaking of the windmills, the buzzing of the fly, the dripping of water onto Strode’s hat – all create a symphony of sounds. It’s not traditional music but it is musical all the same.

The idea to use sound like this was that of Ennio Morricone’s who composed the music for the film. In the past it had always been Leone’s idea to have the music completed before the shooting of the film but he had never been able to do this because of budget and time constraints, but on Once Upon A Time In The West, neither of these were an issue. He had Morricone create distinct themes for all four protagonists – Charles Bronson’s Harmonica, Claudia Cardinale’s Jill McBain, Jason Robards’s Cheyenne and Henry Fonda’s Frank. Leone would then play these themes on the set for the actors so they could time their performances. Later in the editing room, Leone would then cut the film in rhythm with the music so that both image and sound combine harmoniously. As the film progressed and the characters met, the themes would also combine. Much has been written recently about Edgar Wright’s editing technique on Baby Driver but Leone was doing it decades earlier. An example of this is the shot of Frank riding towards the waiting train; in this shot the sound of the horse’s hooves as they hit the ground provides the percussion for the soundtrack.

The undermining of the tropes of the classical western continues the first time we see Henry Fonda’s Frank. Fonda had previously been known for playing wholesome good guys –Tom Joad, the titular lead in Young Mr. Lincoln (1939) (whom Fonda compared to playing Christ) and Juror No.8 in 12 Angry Men (1957) but the first time we see him in Once Upon A Time In The West, he and his men have just slaughtered a family. They appear out of the bush, slowly walking towards the house, where they come across the only survivor – a small boy. We have a close up of Fonda, his well known and likable face and those piercing blue eyes, and we feel almost relief for a moment. Surely this young boy will be ok now? Fonda’s face seems to go through a multitude of emotions – there seems to be empathy and sympathy, there’s even a brief smile – but then he lifts up his gun and shots the boy dead.

When Fonda accepted the role and heard that he was to play a villain he had dark contact lenses made to hide his famous blues eyes. He also grew a moustache and a small pinch of hair under his bottom lip. Leone was having none of it. He had wanted Fonda precisely because of his good guy image. He wanted people to see his eyes and to believe that there could be no hardness, no evil, in this man. That way, when Frank shoots the child, the impact would be so much greater.

Frank works for Mr. Morton, a rail tycoon whose body is as crippled as his character, who wants nothing more that to get to the coast. Morton (Gabriele Ferzetti) represents the true face of the American desire to conquer the West. Not because of an idealised sense of divine right and individualism, but for money. He is the corruption behind the dream that Leone felt so uncomfortable with. He is not a man of dignity but of exploitation and he has no qualms about hiring someone as detestable as Frank to do his bidding.

Whilst there are no real heroes in the film, we do get one man to root for, even if his motivations are unclear until the very end. Whereas Eastwood was famous for playing The Man With No Name, this character, wonderfully performed by Charles Bronson after Clint Eastwood turned the role down, is a man of many names. When Franks asks him who he is, he is given a list of names, each one belonging to a man that Frank has killed. The closest thing this man has to a monika is Harmonica, bestowed on him by Jason Robards’ Cheyenne because each time we see him he plays the same tune on his mouth organ over and over again.

The first time we see Cheyenne he has as much menace as Frank, although with none of the refinement. He has escaped from the law and enters the small trading post where he uses his considerable air of intimidation to terrorise the clientele. It’s also the first time he meets Jill McBain and it’s their growing relationship, one which starts with mistrust but slowly blossoms into what Cheyanne hopes could become a romance (whilst ultimately realising that this could never be). He also seems to be the realist of the group, the man who understands the West better than anyone else. This is illustrated in his speech at the end when he tells Jill to take water for the workers;

“You know what? If I was you, I’d go down there and give those boys a drink. Can’t imagine how happy it makes a man to see a woman like you, just to look at her. And if one of them should, uh, pat your behind, just make believe it’s nothing. They earned it.“

Jill McBain, played by the beautiful Claudia Cardinale, is our guide into this world. We discover the West as she does. She plays an ex-prostitute who had married and crossed half the country to join her new husband and his family, only to discover they have been slaughtered by Frank.

She’s tough but also fragile, she’s scared yet at the same time brave. She has a relationship with each male protagonist, and each relationship reveals a key point about who they all are. She is afraid of Frank but willing to sleep with him to survive, she becomes comfortable with Cheyenne and together they begin to trust each other, and she harbors an attraction for Harmonica, even though she knows that he could never settle down, even if he survived his inevitable confrontation with Frank.

Most of what we learn about the characters comes from their actions. Once Upon A Time In The West is almost three hours long yet apparently there was only 15 pages of scripted dialogue. We learn more from the character’s eyes than we do from their words and this is one of the film’s many attributes.

Leone was always a visual director. Sometimes these visuals were a little rough around the edges and lacked the refinement and polish of traditional classical Hollywood directors. There are zoom shots that lack grace – that start suddenly and end abruptly when Hollywood films would have flowed with majestic grace. There are a few moments where characters are ever so slightly out of focus. But this is not a slight on the film at all. These are certainly not detrimental to the beauty of the film, in fact they add to it’s charm. The roughness of the picture adds to the ambience of the film. These characters aren’t refined and that’s reflected in the direction.

Leone uses some accepted tropes – the low camera behind the gunman, his hands ready to rip his gun out of the holster and shoot from the hip – and takes them to an extreme. His debt to Kurosawa is never more evident than in the finale as Harmonica and Frank face off. It recalls the final moments of Sanjuro (1962) as the two enemies pause, waiting to spring and cut their opponent down. Especially impressive is the tracking shot of Frank entering the train, the bodies of Morton’s men laying fallen across the floor. It’s a simple shot – Frank enters one end of the train and the camera follows a horse’s hind legs to the right until we see Frank exit the carriage and find Morton.

When Once Upon A Time In The West was first released, the critics weren’t kind. They claimed it was too long and too slow. For the US release around 20 minutes was cut but this didn’t help the box office. One crucial scene that was cut was the moment Cheyenne, Harmonica and Jill see each other for the first time at the trading post. Some scenes were lost forever, including one in which Harmonica gets beaten up by Frank’s men. The closest thing to a full, unedited, version was released in France where the critics loved it and, in one cinema, it played none stop for 48 months.

Much like films such as Blade Runner, Once Upon A Time In The West became a success, not because of box office or the declarations of critics of the day, but because of film fans. Its release, at the end of one of France’s most tumultuous years – 1968, perfectly captured the militant, anti-establishment mood of students at the time, not just in Paris and France, but throughout Europe. The long jackets that the characters wore became the fashion choice for students in the later ‘60s and into the ‘70s. The film was also highly influential for many of the later generation’s best directors – Martin Scorsese, George Lucas, John Carpenter, John Milius and Quentin Tarantino. Without it, we wouldn’t have had McCabe & Mrs. Miller (1971), The Outlaw Josey Wales (1976) or Pat Garret & Billy The Kid (1973). Directors like Leone, Sam Peckinpah or Samuel Fuller, helped define this particular period of cinema and beyond.

Like his original Dollars Trilogy (Fistful of Dollars, For A Few Dollars More and The Good, The Bad and The Ugly), Once Upon A Time In The West was the first of a new trilogy which continued with Duck, You Sucker (1971) (also known as A Fistful of Dynamite and Once Upon A Time…The Revolution) and Once Upon A Time In America (1984).

The very reason why Once Upon A Time In The West is so popular with cineastes – it’s rough lyricism, the emphasis on visuals over dialogue, the length and the pacing – would probably be a deterrent for many filmgoers but the undeniable fact is that Once Upon A Time in the West is a magnificent opera of a film. One that not only pays homage to the classic westerns of John Ford, Howard Hawks and Anthony Mann, but also reinvents the genre, modernising it and moving it forward.

Once Upon A Time In The West is undoubtedly one of the greatest westerns ever made. What has attracted so many filmmakers to it, especially the likes of Quentin Tarantino, is obvious. If you haven’t seen it before, make sure you see the full 147 minute version, which is the closest we can currently get to Leone’s complete version. It’s a film whose importance to modern cinema cannot be underestimated. It’s influence is felt in films as far ranging as Reservoir Dogs to Joe Dante’s The ‘Burbs and it will therefore come as no surprise that I give Once Upon A Time In The West my absolute highest recommendation.

Film ’89 Verdict – 10/10