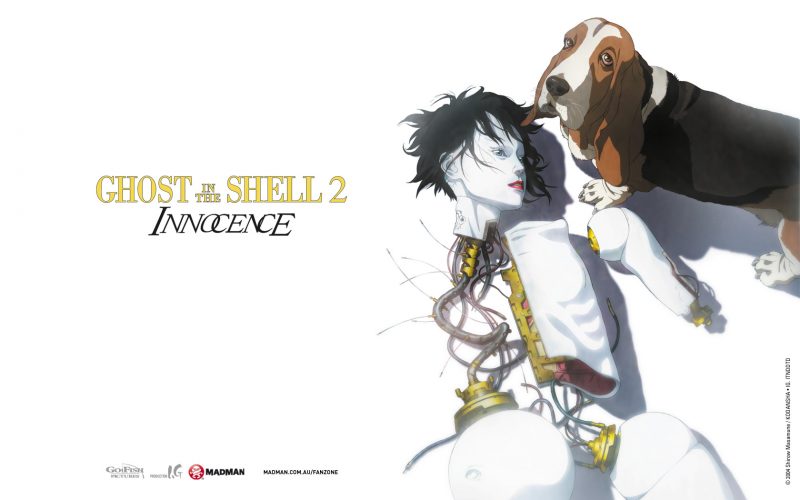

Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence (2004).

Much like the 1995 classic that preceded it, Ghost in the Shell 2: Innocence has a rather basic plot at its center. It’s in pondering far more complex themes that it finds its depth, executed deftly if not as masterfully as the original, game-changing film nine years prior.

Director Mamoru Oshii, returning after almost a decade to tell another existential tale set in a future where the distinction between man and machine is ever blurring, didn’t set out to make a sequel to Ghost in the Shell. Simply titled Innocence in its native country, it was only given the added moniker to appeal to a western audience where Hollywood franchises hold mass appeal. Despite Oshii’s intent, this very much looks and feels like a sequel even if not in the same vein as most western sophomore releases.

Innocence features the return of many characters, and this time around the cyborg Batou is the main protagonist, partnering up with the mostly human Togusa following the disappearance of Major Motoko Kusanagi at the end of Ghost in the Shell. There are many references and allusions to her mysterious fate, and her presence is very much felt even if as largely a spiritual guide for Batou, who proves more than capable of carrying the film in her absence.

Oshii’s sequel is a warmer affair than the previous film, with a more altruistic theme; that all living things are equal. He uses the Basset Hound in all of his works, a choice tied directly to his own personal attachment to and internal experience with his household pet, and here the species features in the form of Batou’s beloved dog. His affection for the animal seems somewhat contradictory to his initial indifference toward life, particularly notable in scenes where he single-handedly massacres would-be attackers with an “act first, ask questions later” type of approach. And yet when emotion escapes him it is usually powerful, and sometimes equal parts subtle. The character’s journey is not so clear cut, though the final shot of the film suggests a newfound appreciation and empathy for the androids following the climactic events that preceded it. Or perhaps it signifies a new level of uncertainty about the physical world.

Again, the film’s actual plot is simple. It involves Batou and Togusa investigating a spout of high-profile murders carried out by child sex dolls, and the investigation leads them to uncovering a dark secret at the center of the company who manufactures them. Through various interactions the characters contemplate the existence of these androids and how different or similar they are to humans. There’s a particularly complex and thought-provoking conversation on the similarities between human children and androids, with the thesis that “raising children is the simplest way to achieve the ancient dream of artificial life”. The themes are heady, and less cleanly explored than the original; this time it’s more manic, with a certain lack of narrative control. When characters start to rant philosophically, it feels less authentic and more a forced element of a script written by a man with too many ideas and too much affection for them to leave any on the cutting room floor. Famous quotes from renowned authors do not bolster your work of art, though there’s clearly been a great deal of thought and attention given that builds layers onto an otherwise simple crime noir tale.

The film blends hand-drawn animation with early 2000s CGI and the contrast is noticeable from one scene to the next. Comparative to the seamless integration of CGI into the 1995 film, the difference between the two styles found in Innocence is quite obvious (a distinction that may be attributed to the dramatic changes in computer generated effects between the mid 90’s and 2000s). While the characters remain hand-drawn, the backgrounds are mostly done digitally in a film that Oshii attributes 40 percent of the work to digital rendering – as opposed to the 10 percent in the first film. The juxtaposition between the characters and the grim, future-urban backdrop gives the film an otherworldly appearance but the characters maintain a photorealistic familiarity. Of its time though it may be, it suits this cyberpunk world; its a more cynical work than the previous film, and there’s a suitable appeal to the film’s time-worn aesthetic.

Togusa’s journey in Innocence is more relatable, even generic, and for good reason. As the most human of the cast, both physically and also as the sole character whose wife and child play an explicit role in the make-up of his identity, the film’s events carry added emotional weight for him. Additionally the haphazard way in which Batou wreaks carnage is in direct conflict with how much Togusa feels he has to live for. In this sense, the relationship between the two partners might be a more fascinating one than that shared between the Major and Batou in the first film.

The best sequence comes just prior to the final act when the two confront a former soldier-turned-hacker obsessed with dolls and with a direct connection to Locus Solus, the company at the heart of the conspiracy (taking its name from French author Raymond Roussel’s 1914 novel). Backed by a suitably creepy music box-like musical composition, the characters find themselves in a sort of time loop while their adversary gives them answers wrapped in riddles. There’s a logical, in-universe explanation for the time loop itself and stands out as one of the most impressive pieces of visual storytelling across both of Oshii’s films. The soundtrack, again by Kenji Kawai, further links this film to the previous one, transporting us to a place that feels deeply unfamiliar, with ancient, eerie tunes that follow the characters like a rogue, foreboding shadow.

The Major’s inclusion, particularly in the final act, makes Oshii’s intent a little unclear. His desire to tell a story disconnected from the first is at odds with her playing such a blatant role. Certainly, viewers will be rewarded for having seen the original for both the already established connection with the character and also the rare but valuable visual cue harkening back to the relationship that she and Batou share. One can’t help but wonder whether the Major’s inclusion was an executive demand during pre-production. There’s certainly an unconventional love story that acts as a through-line, and the film’s thematic reliance on the Major does not feel either forced or unnecessary, but earned and relevant.

Innocence isn’t as good as the original but it is a fine achievement nevertheless. It juggles its own surreal visual style with a tale more human and more accessible than Ghost in the Shell and leans further into the debate on the value of life regardless of the differences between man, machine and everything in between. Its climactic, sea-bound action sequence is rather bland by the standard Oshii sets though less due to production quality and more to do with its diminishing emotional investment. The twist at the end does more to shock and less to add much to the film’s overall sense of injustice, even if it exemplifies the film’s focal point.

Does innocence even exist anymore in the bleak and cruel world of Ghost in the Shell? Togusa is perhaps the most integral part of the film, acting as something of a bridge between the world we know and the cold one he lives in. The ending is somewhat bittersweet, gifting the agents of Section Nine at least something to fight for. But figuring out who the enemy is seems an even less clear task than it did before, and what’s in front of you is never as it seems.

Film ’89 Verdict – 7/10