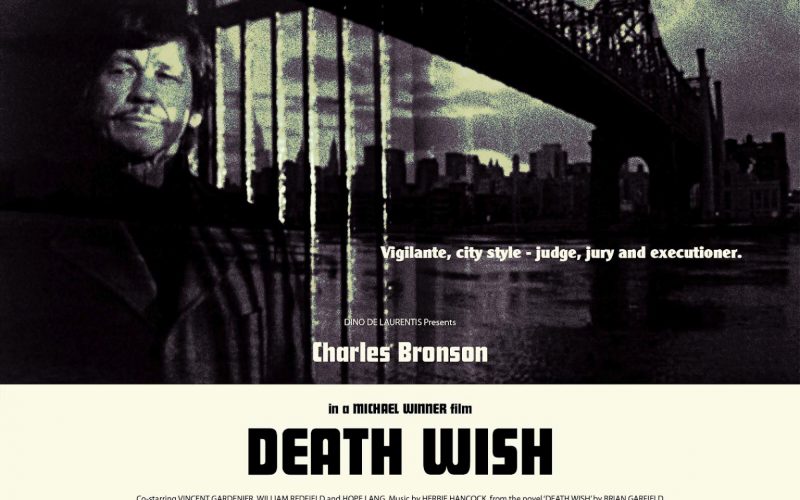

Death Wish (1974).

The early part of the decade that was the 1970s brought with it a new kind of cinematic anti-hero in the wake of the Vietnam War, tailored, whether intentionally or otherwise, for a more cynical movie-going audience who instantly took to the establishment smashing ways of the likes of Detective Harry Callahan who burst onto screens in Don Siegel’s 1971 hit, Dirty Harry. Harry was a maverick cop who played by his own set of rules but was still, at heart, a bastion for good, he just had a drive borne of his bitter resentment of the bureaucracy that often meant the criminals he hounded got off Scott-free.

The almost vigilante style of policing exhibited by ‘Dirty’ Harry Callahan must surely have provided at least some inspiration for author Brian Garfield’s 1972 novel, Death Wish, although the character portrayed in that book was one who was in many ways far removed from Callahan.

Picked up for adaptation into a feature film by producer Dino de Laurentiis, the source material was adapted into a screenplay by Wendell Mayes (Anatomy of a Murder, Von Ryan’s Express, The Poseidon Adventure). Sidney Lumet was initially approached to direct but instead chose to adapt the real-life story of NYPD Detective Frank Serpico with Al Pacino. Jack Lemmon had been the first choice to play the central character in Death Wish, but when Lumet turned down the project, so too did Lemmon.

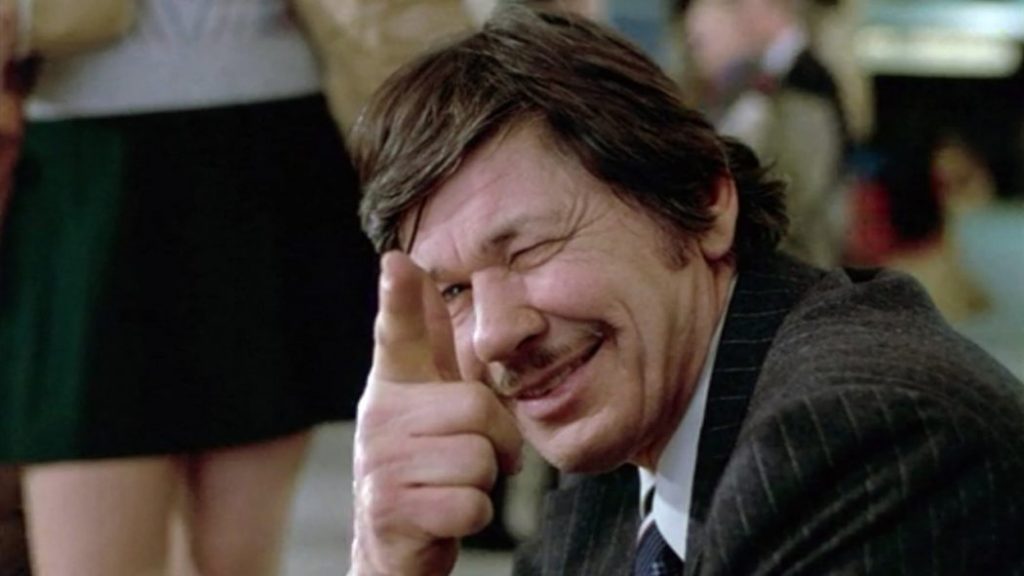

The lead role eventually fell to Charles Bronson. In the two preceding years, Bronson had starred in two successive action heavy crime dramas, The Mechanic (1972) and The Stone Killer (1973), both of which had been helmed by British director, Michael Winner. It was Winner who would direct Death Wish, continuing his working relationship with Bronson and beginning a franchise that would last five films, two more of which would be directed by Winner, and a series that would become synonymous with excessive vigilante violence and be attacked by more liberal minded critics for it’s unrestrained depiction of a man taking the law into his own hands. The Death Wish franchise would go on to define the careers of both Winner and the series’ star Bronson.

From my own personal perspective as someone growing up in the U.K. in the 1980s, Michael Winner was a frequent guest on innumerable chat shows and something of a TV celebrity after becoming a renowned restaurant critic. Known for his unrestrained and often outspoken nature, Winner was liberal and progressive in some of his beliefs and political leanings (he was an early campaigner for gay rights) although a staunch conservative and supporter of Prime Minister, Margaret Thatcher. He often held right leaning attitudes towards such things as the idea of political correctness. Winner was certainly a complex individual but always one who would engage and entertain when on TV, even if he did seem to take a perverse pleasure in courting controversy.

Death Wish opens with our protagonist, Paul Kersey, on a beach vacation with his wife Joanna (Hope Lange). The pair seem blissfully happy and following their return to New York, we learn that Kersey is also a successful architect. The film intercuts between Kersey’s work and his wife shopping for groceries with their daughter, Carol, who is happily married to Jack (who we meet later on). It’s here where Joanne and Carol are followed home from the grocery store by three vile creeps (including a young Jeff Goldblum making his big screen debut as ‘Freak #1’) who burst into Joanne’s apartment. What follows is a harrowing assault whereby Joanne is beaten and has her face slashed with a cutthroat razor and Carol is sexually assaulted. Winner shows enough to shock us but doesn’t push things too far over the boundary into excess and glorification. For a man who would often be associated with lurid and trashy works for a large part of his career, Winner shows a commendable degree of restraint here. The scene is nevertheless brutal and graphic but provides a sufficient impetus for what follows.

Joanne later dies from her injuries and Carol is left in a catatonic state following her ordeal. It’s in the handling of Carol and her regression away from the outside world that seems a little ham-fisted and is one of Death Wish’s few missteps. Steven Keats who plays her dutiful husband, Jack, doesn’t convince in a performance that’s as equally wooden as that of Kathleen Tolan’s as Carol. So much screen time is given to this aspect of the story when it could have been better used to show Kersey dealing with the grief of the loss of his wife which isn’t really placed as front and centre as it could have been as the driving force behind his subsequent spree of vigilantism.

Kersey makes contact with the police who haven’t been able to trace his family’s assailants. It’s not through a lack of effort, it’s just that without a witness being able to look at mugshots and identify them, there’s no way to progress the investigation. This was 1974 and CCTV was practically non-existent in major cities and Death Wish handles the police with a level of respect that doesn’t make them come across as bumbling and incompetent. A key character in this regard is Vincent Gardenia as Police Inspector Frank Ochoa, who we’ll come to later.

Kersey’s colleagues suggest a trip to Tucson, Arizona to handle a project that’s been causing their firm some difficulty. Being extremely adept at his job, Kersey is able to solve the design problems, settle the deal and impress the client, Aimes Jainchill, who takes him to a gun club shooting range. It’s here that we’re given some valuable backstory. Kersey was a veteran of the Korean War but also a conscientious objector, a man of peace. He lives to create, not destroy. That said, he is no stranger to guns, his father having been an avid hunter, something which ultimately cost him his life. Kersey shows himself to be a crack shot in spite of his misgivings about conflict and killing. It’s this key facet of the central character that makes his subsequent transition all the more affecting. Jainchill gives Kersey a gift, which we later find out is a .38 revolver.

Upon his return to New York, Kersey takes the gun with him and is soon accosted in Riverside Park by a mugger who Kersey swiftly dispatches with the gun Jainchill gave him. Kersey flees and from here on in we are witness to his on-going crusade to rid the streets and subways of New York of criminals who prey on the rest of the populace. Kersey’s military training and confidence with guns makes him a highly effective killer. One pleasing aspect of Death Wish is the subtlety and nuance of Bronson’s physical performance when set upon by thugs. He shows just enough of a hint of vulnerability to lure in his quarry before letting loose with his .38.

It’s in Death Wish’s depiction of Kersey’s execution of criminals that the director and star show such a commendable level of restraint. If this was a Dirty Harry film, one would almost expect a moment of relish as our ‘hero’ gloats and spouts a clever one-liner before pulling the trigger but there’s none of that here. Kersey is precisely methodical and quick to finish off his prey, being ever mindful of both his limited ammunition and the need to escape unidentified. This shows him to be just a man, not a superhero, and occasionally he gets injured showing the gravity of the risk he’s taking. This risk isn’t just to his safety but also his liberty as he’s perpetually evading the authorities. This brings us back to Inspector Ochoa.

As Kersey’s nightly activity increases in frequency, the press are abuzz at this newly christened ‘Vigilante Killer’ who’s actions are making waves across the city. Ochoa is seen to employ a logical and methodical approach to apprehending the vigilante but Ochoa’s superiors pressure him to not make a martyr of the vigilante hero who’s actions have had a dramatic effect on the city’s crime figures, something which the police force would obviously be in favour of. Ochoa manages to identify Kersey as a potential suspect, the way in which he does so, perfectly logical and clearly explained. His superiors aren’t telling Ochoa to leave Kersey to carry on, they just want him to stop of his own accord so ask that that he’s sent a clear message that the authorities are onto him.

This all leads to a perfectly believable climax (certainly in terms of what’s been established within the narrative) whereby Kersey is forced to stop his crusade and move on to another city for a clean start having evaded the authorities (a conscious move on their part) and also evading death given the nature of this most dangerous game he’s been playing.

The film ends with a somewhat chilling denouement that suggests that Kersey can’t stop what he’s begun and indeed, in later films in the series, he would become a far more proactive and barbaric angel of death with far less humanity behind those steely eyes. But it’s this first film where a satisfying balance is struck. Kersey’s way of luring the criminals into his snare by leaving himself open to harm gives the film its title. He almost has a Death Wish as he’s pretty much lost everything other than his work which he continues to do by day, killing by night. One of the most surprising aspects that marks the film above that of generic action-thriller is Winner resisting all temptation to have Kersey find and exact revenge upon the thugs who killed his wife. The police had exhausted all leads so the only way Kersey could have apprehended them would have been either by chance or by way of a poorly conceived plot device, something Winner was wise to avoid. Such vengeance could have given Kersey the closure he needed to bring his spree to an end but there’s no such comforting conclusion to be found here. Words such as ‘restraint’ are seldom used to describe Winner’s directorial style when discussing his wider body of work but here it’s an apt description.

It could be argued that Kersey should have been shown to be fallible by killing someone who wasn’t out and out evil but then this would have lessened the impact of that oh-so sinister ending. Death Wish is, to an extent, careful in how much it chooses to assign judgement to the morality of its protagonist’s actions and either chooses not to or is unable to make a clear statement as to whether Kersey is becoming as bad as the crooks he kills. This is mainly due to something that’s possibly to the film’s detriment, in that it shows all the hoodlums in the same light, they’re just evil through and through and this one-dimensionality could have been set aside just to show that no one citizen has a right to be judge, jury and executioner, something that’s pushed to a disturbing extreme in later films in the series.

The Death Wish series would go on to court controversy over its depiction of a man dealing out wanton death and destruction and his exploits would make him seem less sympathetic and relatable. Yet in this first outing for the character of Paul Kersey, both actor and director hit a fine balance of restraint keeping any glorification of vigilantism to a minimum, leaving us, the audience, to question what we would do if criminality took away that which was most precious to us. Winner’s film plays its hand well by taking Kersey, a liberal, educated and kind man of peace and showing that even the best of us, when pushed too far, can be capable of things that go against the very essence of what makes us civilised. Death Wish remains the strongest entry in a series that, in subsequent films, failed to match the quality on display here. With Death Wish, Winner displayed an uncharacteristic degree of directorial craftsmanship in comparison to much of the rest of his body of work as a director. Death Wish deserves to be judged in isolation of its many, lesser sequels and remains arguably Winner’s best film and certainly one of the defining crime thrillers of the 1970s.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 8/10