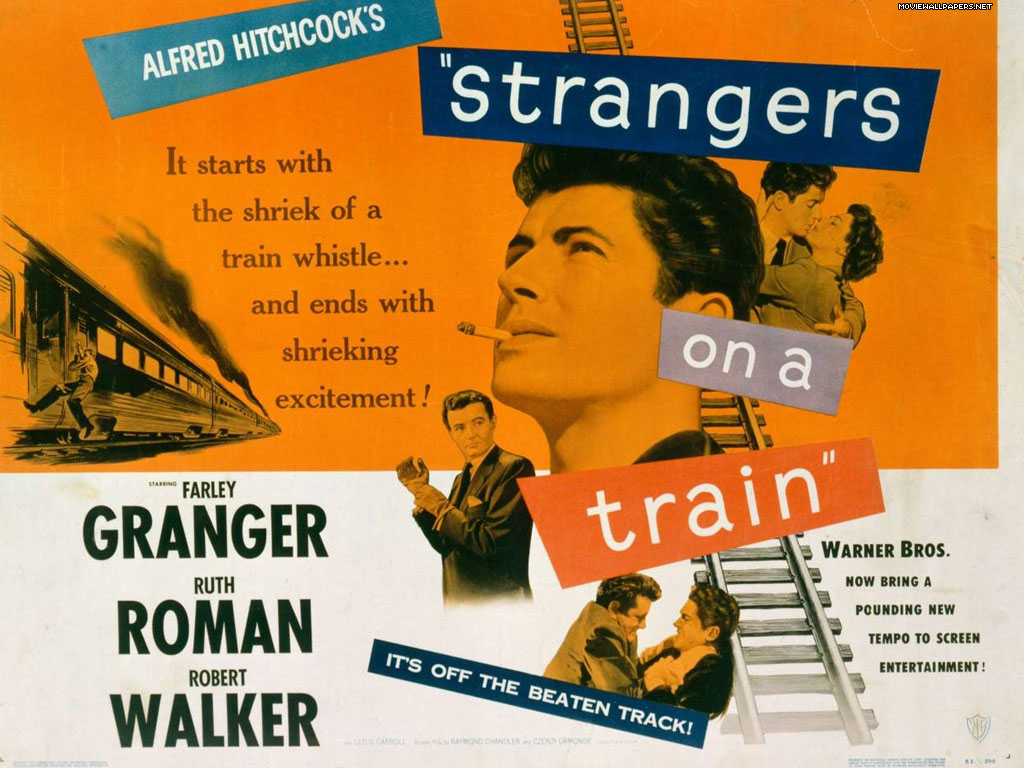

Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train (1951).

*** SPOILER WARNING ***

In the history of cinema there have been only a handful of directors as prolific in both their success and the sheer volume of their work as Alfred Hitchcock. Not only has he crafted some of the finest thrillers ever made, but his permanent influence upon the cinematic landscape is almost incalculable. The span of his career as a director lasted over 50 years and whilst many identify a particular period within that timeframe as his golden years this takes nothing away from the overall quality of his body of work as a whole.

One could spend an age lamenting upon the greatness of The Master Of Suspense, as he was known, but instead I’ll celebrate his career by aiming to cover some of his lesser known films as well as many of his beloved classics that are ripe for reappraisal. Covering every Hitchcock film would be too big a task and frankly some aren’t really worthy of an in-depth analysis. There are some of his earlier films that, for reasons of time and scheduling for now at least, I won’t be covering, such as The 39 Steps (1935) and The Lady Vanishes (1938). But both are absolute gems that I urge you to seek out of you haven’t already seen them.

I’ll start off with a film that came near the mid-point of his career and contains of many of his trademark elements, 1951’s Strangers On A Train.

Based on the novel by Patricia Highsmith, the film begins with our protagonist and antagonist, famous tennis player Guy Haines and spoilt brat, rich boy, Bruno Anthony, meeting by chance one day on a train journey. The film takes no time in getting to the crux of the plot with the wonderfully edgy and chatterbox Bruno haranguing the almost melancholy Guy with his invasive questioning whilst also showing that he knows a great deal about the affairs of his new found, famous friend. A few drinks later and Bruno wastes no time in telling Guy of his particularly ingenious idea of cross murders. Bruno kills Guy’s estranged and troublesome wife, Miriam and in exchange Guy will kill Bruno’s demonstrative father. Bruno’s reckoning being that with no motive whatsoever for each killing, neither killer will ever be found out. Guy rightly brushes off the idea as fantastical nonsense and the two part ways but their fates are already intertwined and the clearly crazy Bruno is more than ready to put his wild plan into motion with or without Guy’s consent.

The aforementioned Hitchcock tropes begin here with an almost repressed homo-erotic subtext as Bruno attempts to seduce Guy with his plan. Bruno has a cat-like, camp charm to him that’s in stark contrast to Guy’s straight-laced, po-faced demeanour. The ironic reversal of roles here regarding their assumed sexuality will be apparent to those who take the time to research the personal real lives of actors Farley Granger and Robert Walker. In another sadly ironic turn, the character of Bruno, with his clear mental health issues, would cruelly mirror that of Robert Walker who’s promising career was cut short by his tragic death not long after the film was released.

We then meet Miriam who Guy is desperate to divorce so he can marry his true love Anne Morton whose father will be Guy’s ticket from his current career to a life in politics. Miriam would have no doubt been seen by audiences at the time as being extremely promiscuous as she cavorts at a fairground with two men, all the while being almost knowingly stalked by Bruno. Here Hitchcock employs some wonderfully subversive in-camera trickery. As Bruno follows Miriam on a boat through a Tunnel of Love his shadow overlaps hers and is seen to devour her like some demonic creature. It’s a wickedly simple portent to what follows and racks up the tension superbly. The subsequent end to the chase is again brilliantly shot in the reflection of Miriam’s glasses which have fallen to the floor.

From this point Guy realises the horrifying reality of what Bruno has done and at first tries to hide the truth from Anne but Bruno is determined to force Guy to make true on their “arrangement” and he gleefully and publicly antagonises Guy with subtly venomous jabs such as his line to Guy about Anne being a “slight improvement over Miriam”. It’s an example of Strangers On A Train‘s satisfyingly witty script and it’s Robert Walker who gets the lion’s share of the best lines. Here begins another of Hitchcock’s recurring themes throughout his films, that of an innocent man wrongly accused.

The film’s pace maintains a perfectly pitched level of tension. Another great moment of Hitchcockian flare is when Guy arrives at a tennis match already in progress, the crowds head’s moving from left to right following the ball all with the exception of one static head, it’s glare fixed firmly on Guy. Bruno ups the ante considerably as his incursion into Guy’s life becomes more overt. We see him gleefully charming socialites at a dinner party held by Guy’s father-in-law to be, just to get them to remember him and his assumed connection with Guy although the scene does build to something of an over the top conclusion. It’s this tendency to overdo things in places and stretch credibility regarding certain plot elements that is one slight flaw with the film and none more so than the carousel set-piece at the end that’s almost comical in how far fetched things become although the final crash of the ride is quite spectacular. Another is Bruno retrieving Guy’s lighter from a storm drain with an arm that would make the Fantastic Four’s Reed Richards proud but these are minor gripes in an otherwise fine film.

Whilst not as well known as some of Hitchcock’s films, Strangers On A Train is just as essential to those who want to see the finer examples of his work. It’s beautifully shot and Hitchcock uses lighting and shadows to great effect throughout. Following the recent restoration the film now looks better than it ever has. Granger is fine as Guy, the perfect straight-man foil to the crazed Bruno but it’s Robert Waker who steals the show with his edgy, camp turn, made tragic by his death later that same year. It would have been interesting to see him become a Hitchcock regular as the crazed mother’s boy he plays here is very reminiscent of a similar character that Hitchcock would unleash on the world nine years later in Psycho. Strangers On A Train is a great little Hitchcock gem and is highly recommended.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 8/10