Alfred Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958).

Hitchcock’s thriller takes its audience to dizzying new heights.

In 1983, Alfred Hitchcock’s 1958 film Vertigo received a theatrical re-release and it was the first time the film had been seen in theatres for well over a decade. Vertigo was one of five of the director’s films that had been the subject of an unusual rights issue whereby the distribution rights to the five films reverted to Hitchcock eight years after their initial theatrical releases.

Hitchcock had removed the five films from circulation, ordering that all the prints be destroyed. Some had not been shown since the 1960s and their disappearance led to them being dubbed “The Missing Hitchcocks”. Exactly why the director deliberately suppressed some of his most admired work for so long is the final Hitchcock mystery left after his death in 1980. The five films include two which are now regarded amongst the best he made in his 50 year career as a director. Another, The Trouble With Harry, was one of his personal favourites. The other two were his brilliant experiment in long-take filmmaking, 1948’s Rope, and the other was his 1956 remake of his 1934 British thriller, The Man Who Knew Too Much.

The reason for the 1983 re-release was that following some protracted negotiations, Universal bought the global distribution rights to all five films for $6 million meaning that the films could once again be shown in cinemas and broadcast on television. The story of their disappearance from screens and eventual reemergence had as many twists and turns as the average Hitchcock plot. Apart from Rope, the films were made in the 1950s under the deal with Paramount which stipulated that ownership of the titles would revert to Hitchcock eight years after their first cinema release. It is and was even then, highly unusual for directors to own the rights to their films, but Hitchcock’s case was not unique with Charlie Chaplin being probably the best example of director-owners. Stanley Kubrick was another who had secured outright control of many of his pictures from A Clockwork Orange onwards.

Upon its initial 1958 theatrical release, Vertigo was met with some rather mixed reviews and a general level of audience apathy. Quite what it was about Hitchcock’s film that failed to resonate with audiences at the time remains unclear but to hazard a best guess, it could be that it was simply a film that was ahead of its time.

*** SPOILER ALERT ***

Vertigo tells the story of a retired San Francisco police detective, John “Scottie” Ferguson (James Stewart), who is hired by an old friend and owner of a shipbuilding firm, Gavin Elster, to investigate the increasingly worrying behaviour of Elster’s wife Madeleine (Kim Novak), who may or may not be suffering from some form of possession, or at least obsession with a woman who committed suicide many years earlier. When Scottie first sees the strikingly beautiful Madeleine he is smitten and agrees to help Gavin. As we learn in the film’s opening scene, Scottie suffers from crippling acrophobia, a fear of heights from which the film’s title is derived.

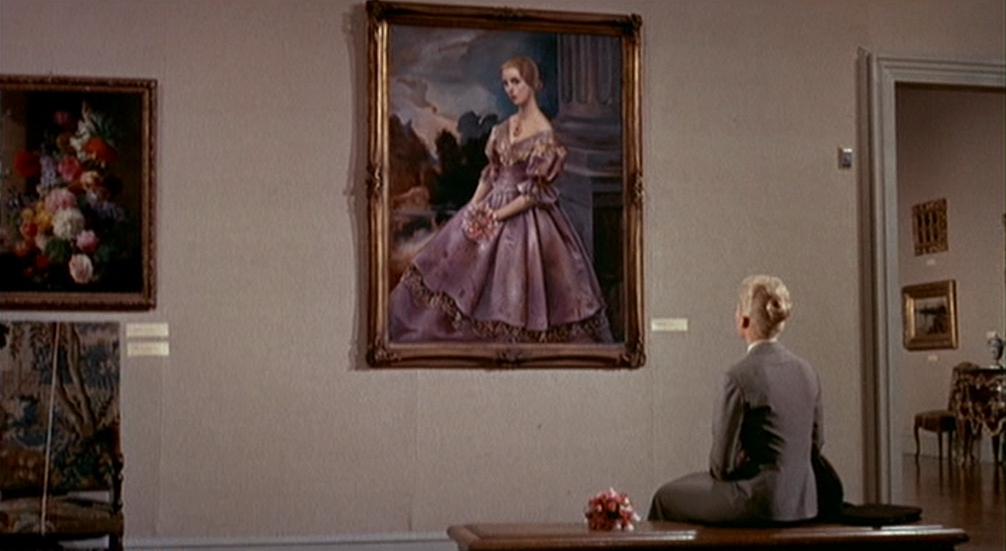

For the first half of Vertigo we follow Scottie as he follows Madeleine first to a florist where she buys a bouquet of flowers which she then takes to the Mission San Francisco de Asís where she stands at the grave of one Carlotta Valdes and on to the Legion of Honor Museum, where she sits and stares at the Portrait of Carlotta. This obsession with Carlotta Valdes leads Scottie to enquire about the long dead woman. He learns that Carlotta committed suicide in 1857 at the age of 26, the same age Madeleine is now. When Scottie and Gavin later discuss the possibility that Madeleine is possessed by Carlotta, Gavin reveals that she was Madeleine’s great-grandmother.

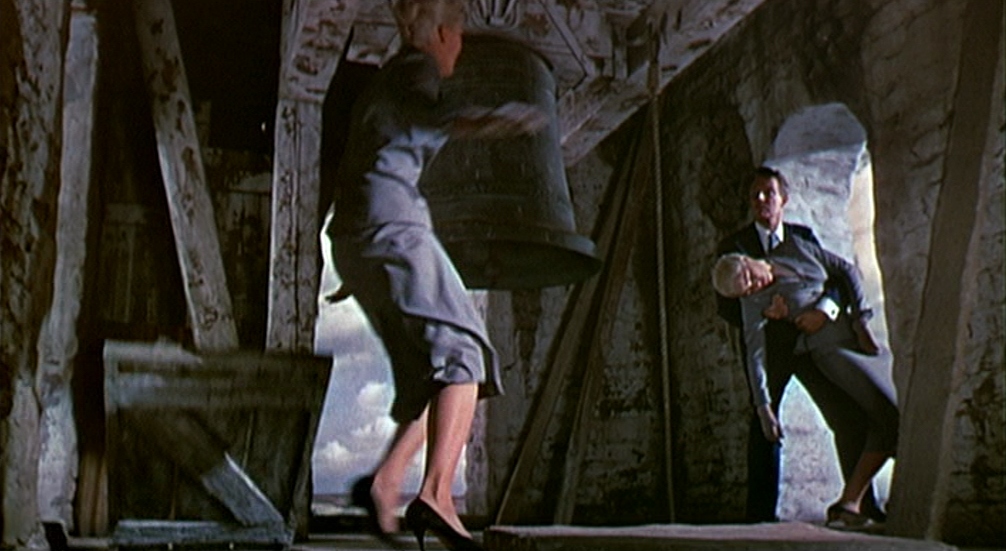

In one of the film’s most famous scenes, Scottie follows her to Fort Point where she jumps into the bay forcing Scottie to rescue her. From here on in, Scottie falls hopelessly in love with Madeleine. When her description of dreams she’s been having leads them both to the childhood home of Carlotta, the Mission San Juan Bautista, Scottie’s acrophobia rears it’s head once again and he is unable to save a distraught Madeleine as she falls (or jumps) from the mission tower to her death. Madeleine’s death is later declared a suicide and Scottie is exonerated of any blame but he spirals into a terrible depression and spends months in a near catatonic state.

During his recovery he sees women whom he mistakes for his lost love and then one day sees a brunette who bears a striking resemblance to Madeleine. He follows this woman back to her apartment and questions her as to who she is and where she’s from. She convinces Scottie that she isn’t his Madeleine – her name is Judy Barton and she moved to San Francisco from Kansas three years ago. Scottie convinces, or more accurately pressures Judy into going to dinner with him. The pair quickly fall in love but their relationship is hindered by Scottie’s controlling nature. He is clearly trying to change Judy’s appearance, her hair colour and wardrobe, to mirror that of Madeleine. It’s at this point in Vertigo that we see the depth of Scottie’s psychological deterioration. It’s all rather subtly handled though as said deterioration is displayed by the degree of obsessive control he tries to exert upon Judy. This downward spiral is made all the more effective and disturbing due to the fact that we are seeing Stewart, a beloved and usually so wholesome Everyman actor, displaying some quite dreadful coercive behaviour towards a woman whom it seems really isn’t deserving of such treatment.

There are many levels of psychology at play throughout Vertigo making it by far one of Hitchcock’s richest films and one most rewarding of repeat viewing. It’s a tale of intrigue, obsession, male aggressive dominance and initially ghostly possession but ultimately cruel betrayal and conspiracy to murder. The often languid pace of the first act is made all the more engaging by the stunning cinematography by Robert Burks who perfectly captures the beauty of San Francisco and its surrounding countryside. The greens and reds of the perfectly lit interior scenes make the most of Edith Head’s wonderful costume designs. It’s easily one of the most beautiful films of the 1950s and the eye candy is matched by a phenomenal score by the legendary composer Bernard Herrmann. Hitchcock does something that even now, having seen the film multiple times, never fails to surprise me. Early in the film’s second act – and there’s a clear three act structure at play here with the first two acts being the meat of the film – he gives away to the audience, but importantly not to Scottie, the film’s big rug-pull, that Judy IS the very same woman that he fell in love with all those months ago.

This earlier than expected twist-reveal throws our expectations into turmoil and turns the direction we thought the film was going in completely on its head. It’s a bold play by Hitchcock to give away the twist so relatively early on. In a way, by letting us, the audience in on the twist whilst keeping Scottie very much in the dark, he’s gifting us with the position of that of a privileged confidant to Madeleine’s secret. It’s leanings towards the supernatural were a meticulously crafted red herring and the time that Hitchcock took to establish Madeleine’s supposed possession make the subsequent about-turn all the more surprising. The Madeleine that Scottie fell in love with was actually Judy, a hired impostor, a lookalike who, after dyeing her hair blonde and a change of clothes, resembled Gavin’s real wife – the real Madeleine Elster, whom Scottie never actually met other than to see her fall from the tower whilst Judy hid at the top knowing that his agoraphobia would prevent him coming all the way up and discovering Gavin’s plot to kill his wife and cover up the crime.

Watching Vertigo now, 60 years on from its initial release, and in context of the entirety of Hitchcock’s vast body of work, it’s undoubtedly a masterpiece in controlled filmmaking. The level of precision craftsmanship at play really is something to behold. The almost sedate pace of the first act is made perfectly palatable as it’s all so incredibly atmospheric and visually splendid. We are sucked into Scottie’s mounting intrigue as to what is causing his quarry’s bizarre behaviour. The visuals, both the combination of stunning real locations and beautifully lit sets, work in tandem with Herrmann’s magnificent score to lift the film above its contemporaries, even those by the same director. The sinister turn after Madeleine’s “death” with a controlling Scottie moulding Judy into something she really isn’t, makes for some suitably uncomfortable viewing. The finale, with a now crazed Scottie and remorseful Judy, ramps the tension up as good as any of Hitchcock’s best works.

For all it’s points of considerable merit, Vertigo does make some rather large narrative leaps of logic that we, the audience, are expected to blindly accept. How did Gavin and Judy know for sure that Scottie wouldn’t be able to traverse the steps and blow open their ruse? Did the investigating officers not examine the tower for evidence? How did Gavin escape from the tower unseen? It seems for all its cleverness, it was a plan that could, and maybe should have failed miserably were it not for the numerous implausibilities built into the plot for convenience. In addition to these, there’s a heavy dollop of melodrama that at times becomes a little too much and the fact that we are also expected to accept an aged Stewart as a viable love interest for Novak, who was half his age, is again stretching credulity.

Some minor flaws notwithstanding, it’s a remarkable film and in 1989 Vertigo was recognized as a “culturally, historically and aesthetically significant” film by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in the National Film Registry in the first year of the registry’s voting. It has featured highly on numerous ‘Best of’ lists including that of Sight & Sound where it placed No.2 in 2002 and a decade later took the No.1 spot from Citizen Kane. Whether Vertigo is Hitchcock’s best film is a matter for endless debate. Personally, I find Rear Window to be a more perfectly crafted film. That said, few would deny Vertigo it’s label of masterpiece for it is a film that was very much ahead of its time and has been hugely influential on the likes of Brian De Palma, Paul Verhoeven (Basic Instinct is a blatant homage to Vertigo) and many more. It lacks the heady romanticism of many of Hitchcock’s other films from that decade and is far more serious in tone, but this is in no way to the film’s detriment. The individual elements that combine to make such a satisfying whole, in particular the work of Robert Burks, Edith Head and Bernard Herrmann are truly to be marvelled at. Vertigo may have confounded some critics on its initial release and it is indeed a film that benefits from and rewards repeat viewings. It will come as little surprise then that Hitchcock’s film gets a recommendation so high that it may well induce the very fear its title describes.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 10/10