Black Narcissus (1947) – Review.

We take a longing gaze at Powell & Pressburger’s visually sumptuous, 70 year old masterpiece.

“The superior of all is the servant of all.”

Many of today’s younger generation of movie fans and cinephiles may be only vaguely aware of the late, great filmmaking duo of Michael Powell & Emeric Pressburger, but in their heyday they were two of the most acclaimed and influential names in film. Movies like The Red Shoes and The Life And Death of Colonel Blimp have been both championed and heralded as classics by the likes of Martin Scorsese who has made no secret of his deep admiration for their films. He has been a strong supporter of the efforts in recent years to preserve these films through painstaking restoration processes so they may endure for many years to come.

Powell & Pressburger were pioneers of shooting in Technicolor, the process by which the huge Technicolor camera would simultaneously capture the filmed image onto three different strips of black and white negative from which three separate black and white records for each of the three primary colours was made into raised matrices. Coloured dyes were then applied to the film, the imperceptibly different depths of layers on the film’s surface would give a slightly different degree of hue and colour saturation. The three separate colour negatives were then combined to give a gloriously vibrant, full colour image. Over time the three different coloured negatives would degrade and lose colour and clarity. The painstaking restoration returned the negatives to their original glory by removing such things as mould, dirt and scratches and some subtle digital enhancements were used to augment the process. The restoration was costly and took many thousands of man hours but the end results were worth it.

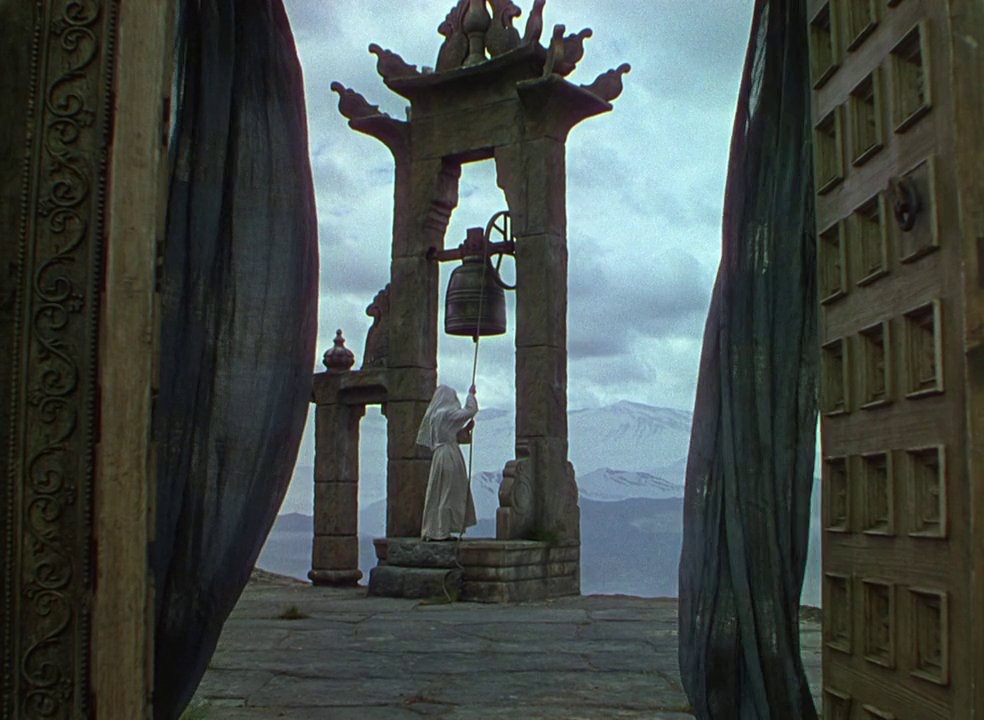

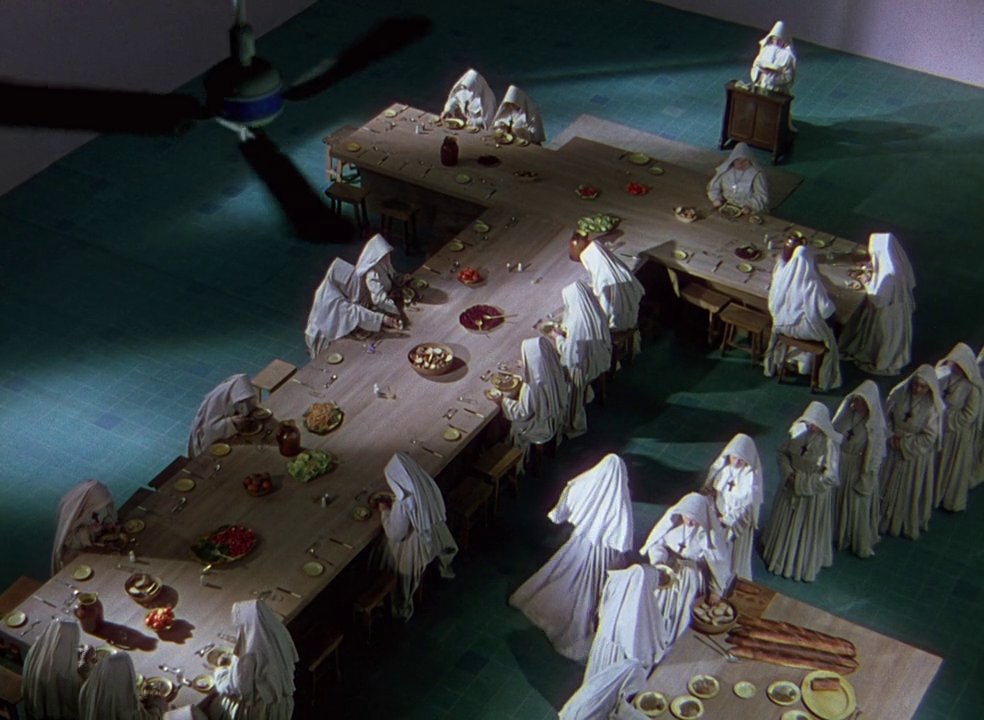

A battle of the spirit over the ever present temptations of flesh, Black Narcissus was adapted from the novel by Rumer Godden and tells the tale of a group of Anglican nuns who set out to a remote Himalayan mountain retreat where they establish a mission in an abandoned harem with the aim of teaching their ways, language and religion to the local natives. Led by Sister Clodagh, played to stoic perfection by the beautiful Deborah Kerr, the nuns face the often harsh climate of their new high altitude home as well as other challenges in the form of slowly burgeoning feelings of temptation and eventually amorality.

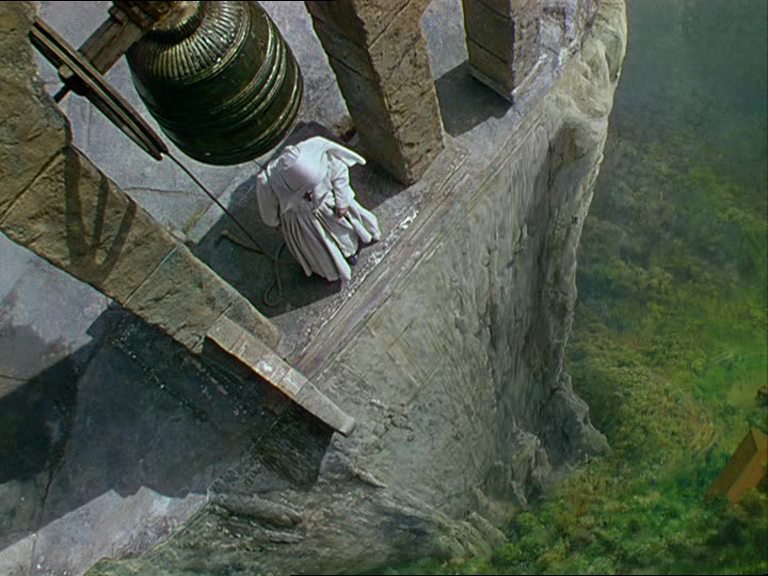

Winner of the Academy Award for Best Color Cinematography by the legendary Jack Cardiff, Black Narcissus is without doubt one of the most staggeringly beautiful films ever made. The overriding element of Black Narcissus that marks it out as a truly marvellous technical achievement is that not a single scene was shot on location in the Himalayas. The entire film was shot at Pinewood Studios, England and several flashback scenes were shot on location in the English countryside. The still jaw-dropping exterior shots are a combination of elaborate sets, intricate models, detailed matte paintings and process shots (the work of W. Percy Day & sons) that flawlessly combine these elements to create a film that, on the whole, completely sells the illusion that the film takes place in and around the mountain retreat. It is such a stunning visual treat that it hardly ever drops the veil of illusion and some of the shots are so convincing that you will struggle to comprehend how the entire film was shot in England. It really is a miraculous filmmaking achievement.

Jack Cardiff was a legendary cinematographer whose fine body of work included not only Powell & Pressburger’s The Red Shoes a year later but also classics such as The African Queen and The Vikings. The art decoration and set decoration is also of a phenomenal standard and would bag the film’s second Oscar for Alfred Junge. Brian Easdale’s great score gives the film a dreamlike quality that bolsters the illusion of the film’s exotic Indian setting. The final act was filmed after the score that would accompany it was recorded so the music could be played on set as the scenes were filmed and therefore timed perfectly to the music. There really are no shortage of expletives to describe how technically wonderful this 1947 film is and to this day, thanks to a painstaking restoration, it looks every bit as gloriously sumptuous.

The performances that stand out are obviously Kerr who brings a resolute strength to the central role she so ably occupies. David Farrar is brilliant as the slightly arrogant but ultimately honourable Mr Dean, a custodian and caretaker of sorts of the former harem. The third main player is Kathleen Byron as the gleefully unhinged Sister Ruth who injects a wonderfully manic intensity giving arguably the film’s most memorable performance. Her latter scenes where she discards her habit in favour of a red dress and make-up are wonderfully dark and for the time, somewhat subversive as she slips into a crazed psycho-sexual fever, so much of her performance played with those piercing eyes.

The performances that stand out are obviously Kerr who brings a resolute strength to the central role she so ably occupies. David Farrar is brilliant as the slightly arrogant but ultimately honourable Mr Dean, a custodian and caretaker of sorts of the former harem. The third main player is Kathleen Byron as the gleefully unhinged Sister Ruth who injects a wonderfully manic intensity giving arguably the film’s most memorable performance. Her latter scenes where she discards her habit in favour of a red dress and make-up are wonderfully dark and for the time, somewhat subversive as she slips into a crazed psycho-sexual fever, so much of her performance played with those piercing eyes.

The film provides a rather heavy handed commentary upon the woes of the pan imperialism the British Empire was so prone to conduct as it spread its influence across its more far flung colonies. Ultimately it’s the indentured arrogance of such a concept that proves the sister’s undoing yet the most faithful among them still adhere to their inherent decency even if the weaker members may succumb to jealousy and eventually madness.

There is a strangely acceptable degree of melodrama at play in Black Narcissus that at times is reminiscent of a gothic horror yet it all works perfectly well in tandem with the exotic surroundings and extremes of endurance the nuns are faced with. There’s nothing particularly unique or original in the concept of the righteous falling to temptation but the overall aesthetic works to bring an otherworldliness to the film that marks it out from other films of the time and it’s very much worthy of the accolades that are still heaped upon it to this day. The film’s bold depiction of certain themes courted some controversy at the time and a few shots, mainly those of Sister Ruth’s openly embraced eroticism, were removed in some territories at the behest of the Catholic Church but thankfully have since been fully restored.

There is a strangely acceptable degree of melodrama at play in Black Narcissus that at times is reminiscent of a gothic horror yet it all works perfectly well in tandem with the exotic surroundings and extremes of endurance the nuns are faced with. There’s nothing particularly unique or original in the concept of the righteous falling to temptation but the overall aesthetic works to bring an otherworldliness to the film that marks it out from other films of the time and it’s very much worthy of the accolades that are still heaped upon it to this day. The film’s bold depiction of certain themes courted some controversy at the time and a few shots, mainly those of Sister Ruth’s openly embraced eroticism, were removed in some territories at the behest of the Catholic Church but thankfully have since been fully restored.

Whether modern audiences, unaccustomed to the predilection towards melodrama of films of this era would fully appreciate Black Narcissus, I’m unsure. From a purely technical standpoint the film’s staggering achievements in cinematography, editing, production design and direction simply cannot be denied. For these reasons alone Black Narcissus would rightly be declared a film worthy of remembrance but throw in some fine performances and a compelling narrative and it’s standing amongst the very greatest films from the golden age of cinema is firmly cemented. Black Narcissus does rely heavily on its aesthetic and on my initial viewings many years ago I found some of its more melodramatic elements a little too on the nose. But like the madness that grows inside Sister Ruth, my admiration for the film as a whole has grown and Black Narcissus is, for me, Powell & Pressbuger’s best film and a must for budding cinephiles eager to educate themselves in the important and influential films of some of the industry’s true greats.

Whether modern audiences, unaccustomed to the predilection towards melodrama of films of this era would fully appreciate Black Narcissus, I’m unsure. From a purely technical standpoint the film’s staggering achievements in cinematography, editing, production design and direction simply cannot be denied. For these reasons alone Black Narcissus would rightly be declared a film worthy of remembrance but throw in some fine performances and a compelling narrative and it’s standing amongst the very greatest films from the golden age of cinema is firmly cemented. Black Narcissus does rely heavily on its aesthetic and on my initial viewings many years ago I found some of its more melodramatic elements a little too on the nose. But like the madness that grows inside Sister Ruth, my admiration for the film as a whole has grown and Black Narcissus is, for me, Powell & Pressbuger’s best film and a must for budding cinephiles eager to educate themselves in the important and influential films of some of the industry’s true greats.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 9/10

Black Narcissus is available on Blu-Ray in the UK courtesy of Network and the US courtesy of The Criterion Collection.