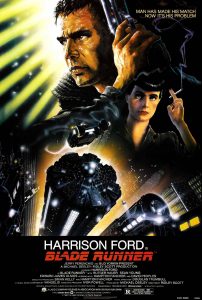

Blade Runner (1982) – Celebrating 35 years of a sci-fi masterpiece.

*** SPOILERS ***

*** SPOILERS ***

2017 marks the 30th anniversary of Ridley Scott’s seminal science fiction film Blade Runner, as well as being the year in which we’ll finally see a sequel in the form of the much anticipated Blade Runner 2049. The story of Blade Runner‘s inception, first as a short story by Phillip K. Dick, through to its troubled production, relative failure upon initial release, and then the years it took on home video through numerous, slightly different cuts, to finally gain the recognition it deserves, is as fascinating a filmmaking story as any. What was once very much a cult film has now gained true classic status and as Ridley Scott’s 2007 Final Cut has shown, may have finally been tweaked to perfection.

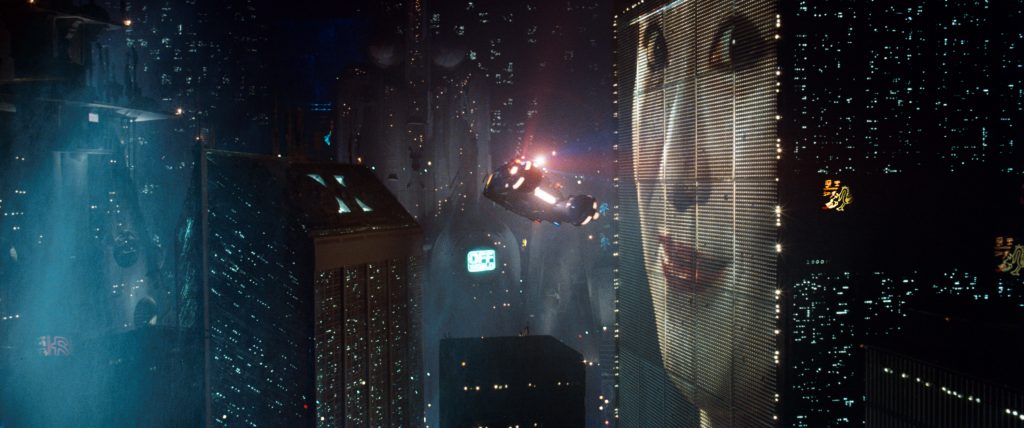

Blade Runner isn’t so much a conventional film in terms of narrative structure, but more of an overall audio-visual sensory experience. In its Final Cut form, free from the much maligned voice-over of the original theatrical cut, it has little in the way of plot exposition. After the scene setting, text introduction, the viewer is placed smack bang into Ridley Scott’s Hellish vision of Los Angeles, 2019, and what a vision it is. Has there ever been a film with such a strong visual style? The neon-lit, smog ridden, rain soaked, multi-lingual world Scott created is a thing of beauty arguably like no other seen in film. The effects and production design take centre stage over plot and narrative, yet service the movie in ways seldom seen before.

The sublime visuals work in perfect harmony with a score by Vangelis, which must surely rank as one of the greatest scores in film and is a truly unique musical wonder, perfectly capturing the often somber melancholy of this dystopian future. Inspired casting is another of the film’s strengths. Harrison Ford’s famous on-set woes and personal issues with the director may have actually added to his somewhat detached performance as Rick Deckard, the Replicant hunting cop brought back in for one last job who may well be one himself. Deckard is thankfully devoid of the cockiness of Ford’s earlier Han Solo and Indiana Jones, and this is one of his finest performances. He brings to the role the same world-weary, downtrodden melancholy that was such a crucial element of the film noir detective stories to which Blade Runner is clearly paying homage.

Rutger Hauer has never been better as Roy Batty, leader of the group of renegade Replicants. His now famous final monologue, allegedly ad-libbed to some extent, describes the film’s core theme of our own mortality. It remains one of the most powerful and memorable scenes in film. You don’t need to know where the Shoulder of Orion is, or what C-Beams are, all you need to know is that during this artificially created life-form’s short, four year existence, he has amassed experiences and memories which, once he’s gone, like our own memories and experiences, will cease to be. Sobering stuff indeed, especially when you consider that Batty, the film’s ‘villain’, in his final moments loved life so much, his life, even the life of the man charged with hunting him, that he saved Deckard from certain death. A fitting finale to a beautiful and thought provoking film. There’s even an argument that Batty isn’t the villain of the piece, he just wants more life, more time to experience the universe and to grow up as it were. Is it actually Deckard, the ruthless hunter of these doomed ‘children’ with their built-in four year lifespans, who’s actually the real antagonist here? That’s the beauty of a film as rich and deep as Blade Runner, you can make your own perfectly justifiable interpretation of the film’s themes and ideas.

That said, for all its unique qualities there are many who simply don’t get what all the fuss is about, and in a way I understand that. My own experience with the film has been something of an up and down roller coaster. Initially when I first saw it in my teens I wasn’t at all taken by it. I thought it ponderous and pretentious to some extent, but slowly I became hooked by its alluring visual flair and found myself returning to it numerous times as I approached adulthood, by which time I’d grown extremely fond of it to the point that when in 2007 with the release of The Final Cut, I was a firm fan of Scott’s masterpiece.

Then, in April of 2015 something I did not expect to happen happened. I was lucky enough to see a one night screening of The Final Cut in a local cinema with a friend who, although a self-confessed film fan, had never seen Blade Runner. Beforehand, I was extremely pleased to finally be seeing the film on the big screen having only ever seen it at home, but two things marred my cinematic Blade Runner baptism. Firstly, the print was poor. My own Blu-Ray copy and Plasma TV set-up at home put it to shame, which hampered considerably my enjoyment of it as I found the grainy, slightly blurred print a big distraction. Secondly, my friend’s own reaction put the film into a new context for me and brought back memories of my own first viewing. He seemed puzzled by it, and the film clearly hadn’t met his own expectations. Without the expository voice-over of the theatrical version, which I knew pretty well by now, he was left clamouring for important plot information that the film now lacks. This is fine for those familiar with the old version, but may cause those for whom the new cut is their only experience of the film, to be left somewhat confused by the rather sparse storytelling. Someone watching the film for the first time would benefit from watching both the original theatrical version and the later Director’s and Final cuts to get the full Blade Runner experience. And whilst the new version is clearly the better film, one shouldn’t really have to refer to two or more versions of the same film to get it the most out of it.

I’ve heard Blade Runner described by some as an exercise in style over substance, and for this again I have no argument. Blade Runner is first and foremost a visually and sonically arresting film that often puts atmosphere before plot and character. This is something that both marks it out from the crowd but also alienates those who may want the plot spoon-fed to them. Watching my friend struggle with the often languid pace and lengthy scenes without frequent dialogue, I was able to see what the film’s detractors dislike about Blade Runner as did I when I first watched it many years ago. That said, based on my own experience of Blade Runner over the years, I have to put aside any possible faults identified by others and declare it the undisputed classic that it is, if for no other reason than the things it gets very much right, of which there are a great many. Aside from that which I’ve already mentioned, there is the set design, special effects, sound design, cinematography and many more technical aspects all of which are truly phenomenal.

Blade Runner may not be to everyone’s tastes but there really is nothing else like it. And if you buy into Harrison Ford and Rutger Hauer’s performances, and that of a stellar supporting cast, which isn’t hard, by the film’s rooftop high-point finale, I defy you not to be moved. I’ll finish by talking about Blade Runner‘s influence on the modern cinematic landscape. The unique visual style of futuristic dystopia that the film showcased has been copied countless times since, sometimes very obviously (Akira, The Fifth Element), sometimes as more of a subtle influence (the constant rain of the unnamed city in Se7en apes that of Blade Runner‘s L.A. of 2019). Either way, Blade Runner has left an indelible mark on Hollywood and science fiction cinema in particular. It’s a film that may require a bit of work from some of its audience but once you immerse yourself in its beauty and flawlessly constructed world, you’ll hopefully come to see that it’s a one of a kind movie that many have tried to copy but none will never be able to truly replicate.

Film ’89 Verdict – 10/10

For a far more in-depth analysis of Blade Runner, it’s making-of, it’s themes and its influence, check out my recent appearance on the Wrong Reel podcast with its brilliant host and creator, James Hancock:

WR248 – More Human Than Human in Ridley Scott’s ‘Blade Runner’

Excellent post!

Thanks Jan, glad you liked it. You should definitely check out the Wrong Reel episode too. We go into almost forensic analysis of Blade Runner there.