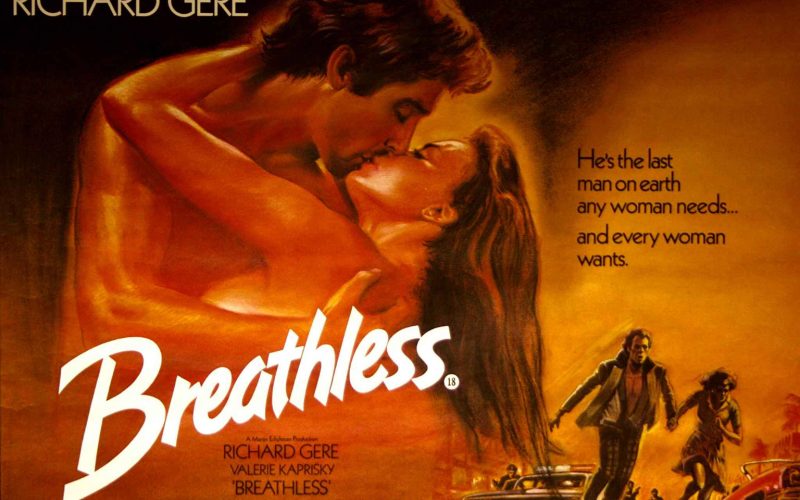

Breathless (1983).

Between 1983 and 1989 director Jim McBride made a loose trilogy of films which explored the flawed psyche of masculinity, not with introspection, naval gazing or sobriety, but in all its brash, entertaining and sometimes destructive glory. He focused on men who had obsessions – women, music, their careers and of course, themselves.

The three films – Breathless, Great Balls of Fire and The Big Easy – offer no narrative link; nonetheless, they are part of a greater whole. They can be enjoyed individually in any order, yet they undoubtedly form a trilogy, and rank, for me if not the wider critical community, alongside recognised masterpieces like Krzysztof Kieślowski’s Three Colours Trilogy. Two feature the music of Jerry Lee Lewis, two star Dennis Quaid, and two are about self-destructive men who are doomed to repeat the same mistakes over and over again, the masculinity that defines them may ultimately destroy them.

The first of these films was Breathless – a loose yet fairly loyal, remake of the Jean-Luc Goddard classic À bout de souffle, about one man on the run from the police. Jesse Lujack (Richard Gere) is a drifter. He has no direction but he does have three obsessions: The Silver Surfer Comics, the music of Jerry Lee Lewis, and French undergraduate Monica (Valérie Kaprisky) with whom he had a brief affair with one night in Vegas. He decides to find Monica, so he steals a Porsche and drives to L.A. On the way, Jesse drives as he lives – music on full volume, speeding along the highway recklessly before coming to the attention of a police cruiser and crashing into a ditch. He finds a gun in the glove compartment and, in a moment of panic and frenzy, accidentally shoots the policeman instantly marking him as a wanted man with his picture in the newspapers.

McBride and writer Kit Carson (Paris, Texas) swap countries and nationalities from the Jean-Luc Goddard original. Goddard famously took the staples of classic American Film Noir and gangster films, transported them to France, and added a distinctly French sensibility. Jean-Paul Belmondo played Michel, a Bogart wannabe, and Jean Seberg was Patricia, Michel’s American girlfriend.

Breathless does the same to À bout de souffle. Jesse (Richard Gere) is no longer French, he’s now an American and Monica is a French student (she shares the same surname as Michel in À bout de souffle – Poiccard). With this transfer to the US, the sensibility was always bound to change. In many respects, both Jesse and Michel are similar and would have undoubtedly got along with each other if they had ever met, and the looseness of style and character are present, but Breathless is definitely an American film.

Whereas À bout de souffle was filmed in black and white, Breathless was shot in resplendent colour. In the opening scenes we see the bright orange beauty of the Nevada desert, and later we are taken into the underbelly of Los Angeles. L.A. is very much a character in this film and in many respects mirrors the dichotomy of Jesse’s character. It’s colourful and seedy, eccentric and mundane, joyful and difficult. We don’t see the Hollywood sign or the glamour of Beverly Hills, we see the scrap yards and grubby bars that are forever bathed in the red light of vice and danger.

Echoing Jesse’s love of the Silver Surfer comics, there is a distinct artificiality about the film. Long dialogue scenes take place in the various cars that Jesse has stolen are filmed with very obvious rear projection (including one scene where Gere talks entirely to himself). There is no attempt at recreating reality, and even the titles are written in a comic book font.

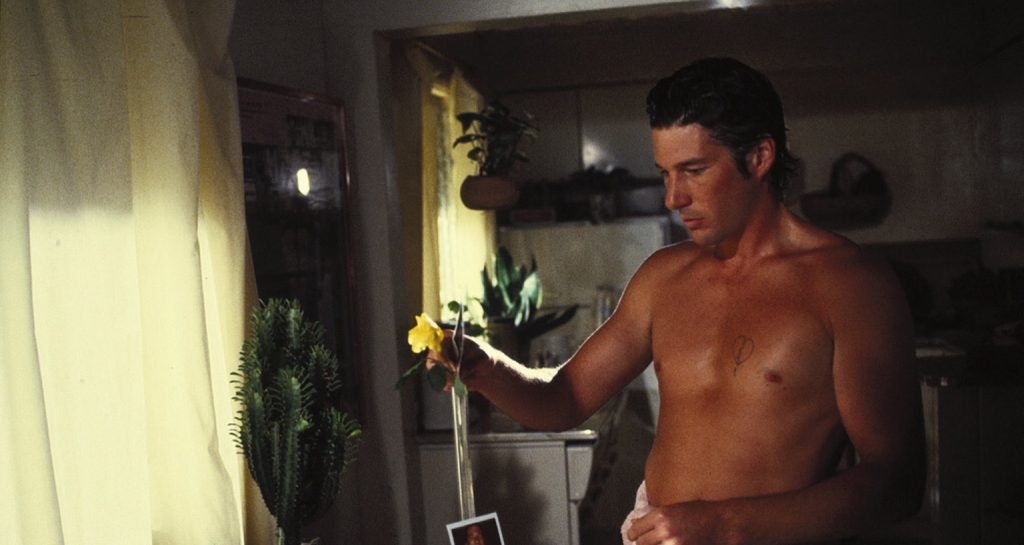

Jesse is always looking for money and can’t leave L.A. without it, yet is seemingly thwarted at every turn. Some of his old acquaintances don’t have money on them, others cheat him, exploiting the predicament he’s in. The centre of the film however, is not driven by a straight forward narrative. Like Great Balls of Fire and The Big Easy, McBride’s focus is on the man. He is a complex character – completely reckless and irresponsible, yet convinced that he’s jinxed. He’s impulsive, jealous and repeatedly states that his philosophy is ‘All or Nothing, baby!’ As Monica points out – ‘You roll the dice too much.’

In many ways his predicament mirrors that of his comic book hero The Silver Surfer. In one significant scene, a young boy tells him that the Silver Surfer sucks because he is always being chased by bad guys and the cops, and ‘he has a chance to get out’, but never takes it.

Of course, the reason Jesse can’t get out is because he’s in love with Monica. He is completely smitten with her yet, at the same time (and in opposition to his love for her) he is too self-absorbed to take her seriously. She wants to be an architect and he disrupts her exam without any thought of the consequences. When she tells him she may be pregnant, he declares that they are moving to Mexico without thought of what she wants. For Jesse, the future doesn’t exist, all that matters is the here and now.

He can swing from one emotion to another in an instant. After an argument with Monica, she goes off to have a shower and Jesse picks up a newspaper and reads a story about how he’s wanted for murder. The jinx that he believes in takes hold of him and for a moment, we can see the worry etched on his face. Then out of nowhere he starts singing and dancing. His mood has lifted completely, his worries and his argument with Monica is forgotten, and he waltzes into the bathroom to join her in the shower.

Monica is a very different character to Jesse. She sees a future and is working towards it, yet there is no doubt that Jesse’s brashness and devil-may-care attitude is alluring. Even though his faults become clearer as the film goes on, she still falls for him over and over again. His is a primal form of masculinity, one that is entirely hedonistic.

What propels Breathless forward is its sheer energy. Just like the pounding piano of Jesse’s idol, Jerry Lee Lewis, the movie has a constant drive that makes it fun to watch and any minor flaws don’t matter. Jesse is an interesting character and there is a destructive inevitability about him that adds an interesting undercurrent to it all. It’s a cartoon, with a cartoon character at its lead, but with a darkness in its soul.

It must be asked, why remake À bout de souffle? It’s a classic of the French New Wave, a film that broke new ground and helped usher in a new, freer and more independent style of filmmaking. Its legacy would be to influence a new wave of American filmmakers in the same way Goddard and writer François Truffaut had themselves been influenced by Hollywood. In isolation, this is a difficult question to answer. Perhaps Jim McBride was exhibiting the same audacity that Jesse exhibits throughout the film.

Breathless does have some high profile fans. Firstly, there’s Quentin Tarantino who described it as one of the ‘coolest’ movies ever made. He said, “Here’s a movie that indulges completely all my obsessions – comic books, rockabilly music and movies,” and there is a poster of the Silver Surfer in Mr Orange’s apartment in Reservoir Dogs in homage to Breathless. Almost 10 years before Tarantino made his first film, Breathless gave us everything that he, and so many others tried to imitate years later.

British film critic Mark Kermode is also a fan and has said, ‘If I had to choose between Breathless and À bout de souffle‘, I would choose Breathless every time.’ This comment seems as audacious as the film, especially given À bout de souffle’s standing in the history of the movies and the love it receives from so many cinephiles, but it’s a statement I’d agree with.

The film has a boundless energy, a cartoonish but charismatic lead character, a fantastic soundtrack, fabulous locales, coupled with the sexiness, artifice and the sheer audacity, not only to remake À bout de souffle but to exceed it, make Breathless essential viewing. In the words of Jerry Lee Lewis, ‘you leave me…. breathless!’

Film’89 Verdict – 8/10