Déjà Vu – Examining Hollywood’s Obsession with Remakes & Reboots.

“A déjà vu is usually a glitch in the Matrix. It happens when they change something.”

So said Carrie Ann-Moss’ Trinity in the groundbreaking 1999 science fiction hit, The Matrix, a film about a future humanity held captive as slaves in an artificially controlled world created by sentient machines. The dèjà vu of which Trinity speaks relates to something repeating itself within the Matrix which represents a glitch or flaw in the system that runs this complex world. It’s the subject of repetition within a complex system, in this case the Hollywood system, that has brought us the news a few months back that Warner Bros, the studio that made The Matrix and its two 2003 sequels, is planning to remake The Matrix less than two decades after it first hit the big screen. Now remakes aren’t the new trend that many would have us believe, on the contrary remakes are something that have been fairly common within the Hollywood system for decades going back to the transition from silent films to talkies.

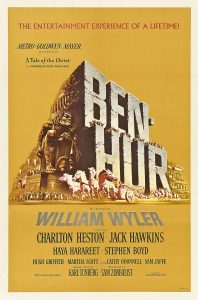

In 1959 William Wyler’s biblical epic Ben-Hur was a huge financial and critical success for MGM who took a risk with the hugely expensive and ambitious film. It would go on to win 11 of its 14 Oscar nominations, a feat only equalled by two films since, Titanic and Return of the King. Yet the 1959 iteration of Ben-Hur was itself a remake of the 1925 silent version of Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ. The 1925 version was also a hugely ambitious and epic film for its time but there was a definite logic to the decision to remake the film in the late ’50s in order to take advantage of both colour, sound and the considerable advances in filmmaking that had been made in the decades between the films. This was an example of a remake of a film that was justified in order to take advantage of the significant difference between silent film and what followed. The 1925 film can be appreciated by connoisseurs of silent film and still impresses with its lavish sets and costumes. The 1959 version even today is a film of monumentally epic proportions that still looks as sumptuous as ever thanks to a recent restoration on Blu-Ray that makes the film look like it was shot yesterday. The name Ben-Hur will be familiar to younger audiences due to the fact that yet again the original source material, the novel by General Lew Wallace, was remade yet again in 2016 and this time was a huge critical and commercial failure. Simply put the 2016 iteration of Ben-Hur was a poorly written and directed film that ultimately did not need to be made. The 1959 version put a full stop on a cinematic adaptation of Wallace’s story. It was such a fine production on a scale that few films since would be able to equal that remaking it seems illogical. Yet the recent version is redolent of a trend that is fast becoming a plague upon modern Hollywood, that of the unwanted, unnecessary and unsuccessful remake/reboot.

In 1959 William Wyler’s biblical epic Ben-Hur was a huge financial and critical success for MGM who took a risk with the hugely expensive and ambitious film. It would go on to win 11 of its 14 Oscar nominations, a feat only equalled by two films since, Titanic and Return of the King. Yet the 1959 iteration of Ben-Hur was itself a remake of the 1925 silent version of Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ. The 1925 version was also a hugely ambitious and epic film for its time but there was a definite logic to the decision to remake the film in the late ’50s in order to take advantage of both colour, sound and the considerable advances in filmmaking that had been made in the decades between the films. This was an example of a remake of a film that was justified in order to take advantage of the significant difference between silent film and what followed. The 1925 film can be appreciated by connoisseurs of silent film and still impresses with its lavish sets and costumes. The 1959 version even today is a film of monumentally epic proportions that still looks as sumptuous as ever thanks to a recent restoration on Blu-Ray that makes the film look like it was shot yesterday. The name Ben-Hur will be familiar to younger audiences due to the fact that yet again the original source material, the novel by General Lew Wallace, was remade yet again in 2016 and this time was a huge critical and commercial failure. Simply put the 2016 iteration of Ben-Hur was a poorly written and directed film that ultimately did not need to be made. The 1959 version put a full stop on a cinematic adaptation of Wallace’s story. It was such a fine production on a scale that few films since would be able to equal that remaking it seems illogical. Yet the recent version is redolent of a trend that is fast becoming a plague upon modern Hollywood, that of the unwanted, unnecessary and unsuccessful remake/reboot.

The fairly recent news of Warner’s decision to remake The Matrix has yet to confirm whether this will be a retelling or a reimagining of the original film(s) but further reports later came through suggesting that the newly planned venture will possibly be a prequel or origin story of sorts. Whether this is a knee-jerk reaction by the studio to the outcry the initial announcement caused I’m not sure but it’s certainly possible. Either way a remake of any kind of The Matrix and it’s sequels isn’t something that the majority of filmgoers seem to want, certainly not judging by the reactions that were seen on social media following Warner’s announcement. Whether you’re a fan of the 1999 original or not, one thing can’t be denied, when it first hit theatres that year it felt incredibly fresh and innovative, something that can’t be said for the vast majority of remakes that have become alarmingly frequent in the last decade or so.

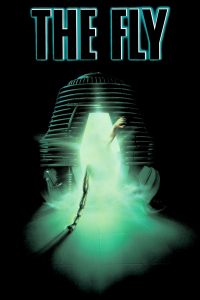

To make matters worse yet another remake of a remake was announced the same day that the Matrix news dropped when it was reported that The Fly (1958/1986) was to be remade. The 1958 original was one of the multitudinous monster B-movies of the 1950’s and charmingly hokey when viewed from a modern day perspective. David Cronenberg’s 1986 remake was and still is a visceral masterpiece of grotesque body horror but it also had a definite heart to it with its depiction of a doomed love affair. It’s rightly regarded as one of the all time great remakes as it takes a film that could hardly be described as a classic of cinema and updates the formula to create a new film that is very much a modern classic. John Carpenter had done the exact same thing four years earlier when he remade the 1951 science fiction film The Thing From Another World. Carpenter’s 1982 retelling was a significantly different film to the original. It expanded upon the central themes of the novel Who Goes There, upon which the ’51 version was loosely based and much like Cronenberg’s film, Carpenter’s was a gory and terrifying take on the material. Whilst a commercial failure upon its initial release the 1982 film is now considered an outright classic melding of the horror and science fiction genres and is arguably the director’s best film. Both 1980’s versions of these ’50s B-movies are perfect examples of remakes done well and with the best intentions, to take the somewhat shaky original films and improve upon them in every conceivable regard. It’s a common sense approach that seems to be lost on a modern Hollywood that instead of looking to improve upon films that didn’t really work first time around, is now refitting beloved classics in the hope of cloning their success.

To make matters worse yet another remake of a remake was announced the same day that the Matrix news dropped when it was reported that The Fly (1958/1986) was to be remade. The 1958 original was one of the multitudinous monster B-movies of the 1950’s and charmingly hokey when viewed from a modern day perspective. David Cronenberg’s 1986 remake was and still is a visceral masterpiece of grotesque body horror but it also had a definite heart to it with its depiction of a doomed love affair. It’s rightly regarded as one of the all time great remakes as it takes a film that could hardly be described as a classic of cinema and updates the formula to create a new film that is very much a modern classic. John Carpenter had done the exact same thing four years earlier when he remade the 1951 science fiction film The Thing From Another World. Carpenter’s 1982 retelling was a significantly different film to the original. It expanded upon the central themes of the novel Who Goes There, upon which the ’51 version was loosely based and much like Cronenberg’s film, Carpenter’s was a gory and terrifying take on the material. Whilst a commercial failure upon its initial release the 1982 film is now considered an outright classic melding of the horror and science fiction genres and is arguably the director’s best film. Both 1980’s versions of these ’50s B-movies are perfect examples of remakes done well and with the best intentions, to take the somewhat shaky original films and improve upon them in every conceivable regard. It’s a common sense approach that seems to be lost on a modern Hollywood that instead of looking to improve upon films that didn’t really work first time around, is now refitting beloved classics in the hope of cloning their success.

There are many recent examples of medium to big budget remakes of classics from the ’60s (Planet of the Apes), ’70s (Halloween, The Wicker Man), ’80s (Ghostbusters, RoboCop) and ’90s (Total Recall) that, by very way of their existence, have angered fans of the originals due to their failure to recapture what made the originals so great in the first place. Much of what has hamstrung these films is an almost uniformly present lack of understanding on behalf of the studios and filmmakers as to why the originals worked. In the case of José Padilha’s 2014 RoboCop, MGM wanted to maximise the film’s box office by appealing to as wide a demographic as possible and imposed a PG-13 limit on the film’s rating that robbed it of the ultra violence that was one of the key components of the original’s dark, gritty, dystopian tone. The remake felt so light and fluffy and inoffensive in comparison that coupled with its unremarkable execution left a film that walked a safe path to banality. Clearly MGM banked on the cult status of the original being enough to ensure at least a moderate return on its investment. Alas worldwide the film took only two and a half times its $100 million budget, taking into account the marketing costs that aren’t included in the film’s production budget, it was not a viable commercial success and no follow up has been mooted. The point I’m trying to make is that, on the whole, the studio’s obsession with watering down adult material to aim to a larger audience simply doesn’t work on a creative and commercial basis.

There are many recent examples of medium to big budget remakes of classics from the ’60s (Planet of the Apes), ’70s (Halloween, The Wicker Man), ’80s (Ghostbusters, RoboCop) and ’90s (Total Recall) that, by very way of their existence, have angered fans of the originals due to their failure to recapture what made the originals so great in the first place. Much of what has hamstrung these films is an almost uniformly present lack of understanding on behalf of the studios and filmmakers as to why the originals worked. In the case of José Padilha’s 2014 RoboCop, MGM wanted to maximise the film’s box office by appealing to as wide a demographic as possible and imposed a PG-13 limit on the film’s rating that robbed it of the ultra violence that was one of the key components of the original’s dark, gritty, dystopian tone. The remake felt so light and fluffy and inoffensive in comparison that coupled with its unremarkable execution left a film that walked a safe path to banality. Clearly MGM banked on the cult status of the original being enough to ensure at least a moderate return on its investment. Alas worldwide the film took only two and a half times its $100 million budget, taking into account the marketing costs that aren’t included in the film’s production budget, it was not a viable commercial success and no follow up has been mooted. The point I’m trying to make is that, on the whole, the studio’s obsession with watering down adult material to aim to a larger audience simply doesn’t work on a creative and commercial basis.

Even when a remake doesn’t shun the adult approach of an original, often the execution or general approach the film takes results in a film that fails to offer anything new and retreads old ground too closely such as Gus Van Sant’s much maligned 1998 shot-for-shot remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 classic, Psycho. Why take a film that’s almost a flawless representation of the work of one of Hollywood’s very best auteurs and make it again with far a less talented cast and crew? At what point did the studio think this was a good idea? The answer to when it’s a good idea to remake a film can perhaps be seen in remakes of yesteryear. When John Sturges took Akira Kurosawa’s 1954 masterpiece, Seven Samurai and retooled it in the style of a western, he took the general conceit of the original and did something different enough with it to warrant its existence. Aside from this general thematic approach, great care was taken with the casting of The Magnificent Seven (1960), and the script and direction were top notch. The resultant film, whilst similar in plot to Kurosawa’s acclaimed original, doesn’t rip it off wholesale and puts a new spin on the samurai epic. Other westerns had their roots in Japanese samurai films and were considered loose remakes. Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961) and Sanjuro (1962) were retooled into Spaghetti Westerns by Sergio Leone in the form of the first two parts of his Man With No Name Trilogy, A Fistful of Dollars (1964) and For A Few Dollars More (1965). Again they were different enough from the originals to warrant their existence and were retooled and repackaged sufficiently so as to appeal to a different audience.

Even when a remake doesn’t shun the adult approach of an original, often the execution or general approach the film takes results in a film that fails to offer anything new and retreads old ground too closely such as Gus Van Sant’s much maligned 1998 shot-for-shot remake of Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 classic, Psycho. Why take a film that’s almost a flawless representation of the work of one of Hollywood’s very best auteurs and make it again with far a less talented cast and crew? At what point did the studio think this was a good idea? The answer to when it’s a good idea to remake a film can perhaps be seen in remakes of yesteryear. When John Sturges took Akira Kurosawa’s 1954 masterpiece, Seven Samurai and retooled it in the style of a western, he took the general conceit of the original and did something different enough with it to warrant its existence. Aside from this general thematic approach, great care was taken with the casting of The Magnificent Seven (1960), and the script and direction were top notch. The resultant film, whilst similar in plot to Kurosawa’s acclaimed original, doesn’t rip it off wholesale and puts a new spin on the samurai epic. Other westerns had their roots in Japanese samurai films and were considered loose remakes. Kurosawa’s Yojimbo (1961) and Sanjuro (1962) were retooled into Spaghetti Westerns by Sergio Leone in the form of the first two parts of his Man With No Name Trilogy, A Fistful of Dollars (1964) and For A Few Dollars More (1965). Again they were different enough from the originals to warrant their existence and were retooled and repackaged sufficiently so as to appeal to a different audience.

The trend of Hollywood remaking non-English films for a new audience isn’t a new one and even today is a successfully applied approach to remakes. Examples include Terry Gillian’s Twelve Monkeys (1995), Christopher Nolan’s Insomnia (2002), and Martin Scorsese’s The Departed (2006) to name but a few. The strong stylistic flavour each of these acclaimed directors brings to the existing material coupled with their established clout as filmmakers shows that in these examples the studios made the films for the right reasons as opposed to the cash-in approach that many remakes seem to be born of in recent years.

Many other modern remakes of American films of old have been well executed and made with such suitable reverence and understanding of what made the originals a success that their existence is at least justified. In 2004 Zack Snyder took the underlying social commentary on consumerism gone mad of George A. Romero’s 1978 zombie classic, Dawn Of The Dead and with the bigger budget and modern make-up and effects techniques at his disposal, created a remake that captured much of what worked in the original. Snyder’s own unique comic book visual style gave the film just enough of its own aesthetic identity to mark it out as something more than a cash-in rehash. Most importantly Snyder’s film retained the core idea of the original, that we are mindless slaves to consumerism. It remains one of Snyder’s best films.

Many other modern remakes of American films of old have been well executed and made with such suitable reverence and understanding of what made the originals a success that their existence is at least justified. In 2004 Zack Snyder took the underlying social commentary on consumerism gone mad of George A. Romero’s 1978 zombie classic, Dawn Of The Dead and with the bigger budget and modern make-up and effects techniques at his disposal, created a remake that captured much of what worked in the original. Snyder’s own unique comic book visual style gave the film just enough of its own aesthetic identity to mark it out as something more than a cash-in rehash. Most importantly Snyder’s film retained the core idea of the original, that we are mindless slaves to consumerism. It remains one of Snyder’s best films.

The intention of this piece isn’t to lambast the idea of a remake or reboot, on the contrary some of my my very favourite films are remakes such as the aforementioned Ben-Hur (1959), The Magnificent Seven (1960) and The Thing (1982) and there are many more you can add to that list. Much of Hollywood’s output is based on an existing book, play, TV show, foreign language film or other form of media so the reuse of a piece of intellectual property forms the basis of the majority of mainstream film these days. It’s the glut of unwanted, lazy remakes, reboots and rehashes that is the cause of the term ‘remake’ having a stigma attached to it and it’s these films that are the cause of the problem. If the Matrix reboot/remake/prequel/sequel or whatever form it ultimately arrives in is a fresh take on the original that in some way expands upon it in some constructive and well thought out way then I’ll take it but given how particularly fresh and inventive the original felt less than two decades ago, the chances are this is another case of a big studio clamouring for ideas to make money.

Sadly Warner Bros, the studio responsible for this new proposed Matrix, have had a less than successful string of big budget output of late. After it’s huge success with the Lord of the Rings and Harry Potter series that both began in 2001 it’s failed to recapture the creative magic that made those series such huge critical and commercial successes. It’s inability to get its DC Comics Expanded Universe of films up and running in the same way Disney have with its Marvel Cinematic Universe and recently acquired Star Wars series, is a sign of a studio lacking in the creative drive it once had. Whilst I always try to remain non-judgemental until a film is released, the prospect of a Matrix reboot seems to represent the same lack of fresh ideas that gives at least some credence to the stigma surrounding the term remake.

To return to Trinity’s opening quote from the 1999 original, déjà vu represents a glitch, a problem in the system when the powers at be change something yet it’s keeping to the same tried and tested formula that’s a big part of this problem. Ultimately I think the answer to the problem lies with what films are chosen to be remade and the simple solution would be to leave the classics alone and remake those films that, for whatever reason at the time just weren’t that great. Films like Ocean’s 11 (1960), a film that nobody held in any great regard yet which was remade in 2001 and improved upon in several ways, the most important being the writing. It’s an argument I keep going back to time and time again, good writing costs nothing and will made a strong foundation for any film, be it an original idea, a sequel or a remake. The thing that hamstrings the cash-grab remake is one of a lack of artistic integrity where the initial aim of the studio is to take a ready made film and repurpose it quickly and with little real care and consideration for the source material in the hope that it will offer at least a moderate return on investment. It’s my belief that this stems from a lack of ideas that sadly permeates the majority of medium to big budget Hollywood films these days.

To return to Trinity’s opening quote from the 1999 original, déjà vu represents a glitch, a problem in the system when the powers at be change something yet it’s keeping to the same tried and tested formula that’s a big part of this problem. Ultimately I think the answer to the problem lies with what films are chosen to be remade and the simple solution would be to leave the classics alone and remake those films that, for whatever reason at the time just weren’t that great. Films like Ocean’s 11 (1960), a film that nobody held in any great regard yet which was remade in 2001 and improved upon in several ways, the most important being the writing. It’s an argument I keep going back to time and time again, good writing costs nothing and will made a strong foundation for any film, be it an original idea, a sequel or a remake. The thing that hamstrings the cash-grab remake is one of a lack of artistic integrity where the initial aim of the studio is to take a ready made film and repurpose it quickly and with little real care and consideration for the source material in the hope that it will offer at least a moderate return on investment. It’s my belief that this stems from a lack of ideas that sadly permeates the majority of medium to big budget Hollywood films these days.

As Alfred Hitchcock once put it, “the key ingredients to a good film are the script, the script and the script.” If a film has the foundation of a solid script, whether an original idea, a remake or adaptation from another medium, half the work of the filmmakers is done and whilst casting big names and the use of costly effects can push budgets up making a greater return more important to studios, great writing and close scrutiny of the writing process of a film costs nothing. When will this simple conceit once again be the driving creative force behind the mainstream film industry as it was in the 1970s? It’s one that’s at the forefront of indie filmmaking yet as you go up the chain from small independents to the large established studios, this ethos is lost amongst corporate greed at the expense of artistic integrity and at the end of the day, what is film if not a form of art?