Directors Series – Christopher Nolan, Part 1 – Memento (2000).

Christopher Nolan’s Memento is a loose adaptation of the short story Memento Mori, written by his brother Jonathan Nolan and based on a concept he pitched to Chris during a road trip the two took together in the ‘90s. Since its critically acclaimed release in 2000, it has become a cult classic and is considered one of the best films of its decade.

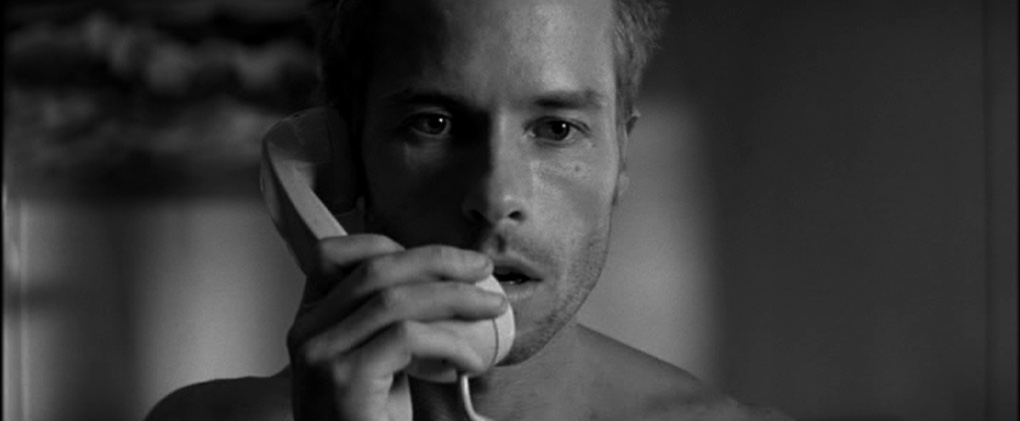

Two separate storylines weave through the overarching narrative of Memento, each set in a separate period of time. These are easily identifiable; one is black and white, and one is colour. The colour scenes start from the moment Leonard – played by Guy Pearce, in a role Brad Pitt showed plenty of interest in before scheduling conflicts ruled him out – shoots and kills his acquaintance, Teddy (Joe Pantoliano). From here the film works backwards from that moment, piecing together the mystery that is Leonard’s life and his quest for answers and ultimately, peace. The black and white sequences mostly take place inside Leonard’s apartment and these are events happening prior to everything that takes place in colour.

The two storylines meet at the centre by the end of the film. If it sounds confusing to those who have yet to see it, it should. It is without a doubt worth watching two or three times after the first viewing. A couple of months after the brothers came up with the story, the director had the idea of telling it backwards. He did however, write the screenplay in chronological order and opted to reorder it only after it was on paper.

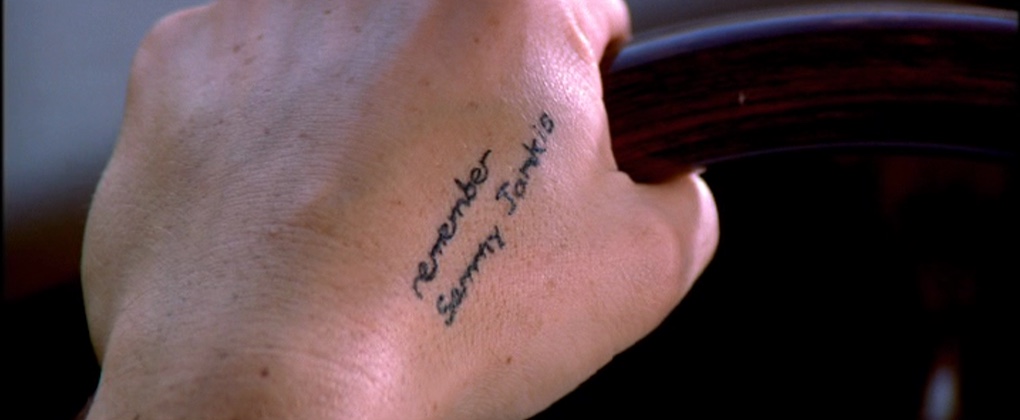

It’s a masterfully edited film. Each scene, working backwards through the narrative, ends a few seconds into the beginning of the previous scene, a constant reminder of where each sequence fits into the equation. It’s a perfect example of structure benefiting story, as we’re forced to experience Leonard’s short term memory condition as accurately as possible. Leonard’s story is a tragic one; his wife is murdered and he is injured so extensively that his brain can no longer create new memories. He tattoos his body with notes and reminders, information that will help him to learn who murdered his wife. Nolan, a noted lover of film noir, utilises many of the tropes inherent in that genre – albeit much of it with a twist. We spend most of our time piecing together the mystery, but the script offers many curious turns borne directly from the hero’s debilitating injury.

Carrie-Ann Moss plays Natalie, the film’s femme fatale and a character who offers plenty within the confines of her subplot – rich with material despite the limitations. Pearce is perfect for the role, balancing Leonard’s pain with his motivation and nailing his line delivery. Particularly resonant is a monologue in which he ponders how he is supposed to mourn and move on when his perception of time has been erased. It’s perhaps the film’s best scene and a firm example of the complexity of theme that Nolan meticulously handles.

Initially written in sequences of five minutes each, these appear to become longer as the film progresses. Plunging deeper into the mystery, the questions pile up. Each colour scene acts as a hook of its own, committing the viewer to the next just so that an answer might be offered. The final scene of the film – the chronological beginning of the story – mirrors the opening scene in which Teddy is shot. Both scenes take place in an abandoned warehouse, and both involve a dead body.

There’s plenty of this symmetry throughout, such as when in the black and white scenes, Leonard tells an unknown caller on the phone about Sammy Jankis. Sammy was a man who suffered from a similar memory problem and whose wife’s claim for insurance at the company Leonard worked at was knocked back due to it being deemed that, physically, Sammy should be capable of retaining memories. Leonard himself notes the irony in this.

There’s a constant sense of curiosity and sorrow as we learn more about Leonard and see others taking advantage of his illness. The lengths that the character goes to so that he may have a purpose to keep on living are staggering, and he slots right into a world so utterly mundane that his story feels at times enormous but at other times as small as anybody else’s. Many of the seeds of Nolan’s future films are planted in Memento, such as his preoccupation with time and memory as dramatic and central themes, major ending reveals raising more questions than answers, and the damaged hero’s quest after suffering loss.

The difference here, as opposed to all of his other films, is that we’re given Leonard’s point of view from start to finish. At times this isn’t true – sometimes moments are presented for our eyes only, things that Leonard misses so that we’ll understand the kind of manipulation that’s being exercised on him – but in these cases Leonard would not remember if he had seen them anyway.

The very first shot of the film features a hand waving a Polaroid image in the background of the credits. Only the photograph doesn’t become clearer, but instead fades away. Leonard’s memory might fade just as the image does, but Memento has earned its place in the memory of filmgoers, and will not fade from memory quite so easily.

Film ’89 Verdict – 9/10

This is a perfect film to me that totally mesmerized me when I saw it in the theater. Guy Pierce is pitch perfect, the script is shape, & the way it was shot segment wise but backwards makes this a one of a kind experience. Nolan is hard to believe grows from this 2nd feature to go on to build one of the most impressive careers of the recent batch of directors. Great article.