Directors Series – Christopher Nolan, Part 6 – Dunkirk (2017).

Christopher Nolan’s retelling of the events of Dunkirk opens with a group of boys in a deserted town, scavenging for perhaps food but most certainly water. Before long the silence is burst by gunfire, piercing the air and all but one of the boys. He leaps over a fence and is again fired upon, this time by allies. Once they realise, he’s thrust behind friendly lines unceremoniously. He races away from the carnage as bullets begin to fly once again. This whole scene is a summation of the events to come. These soldiers just want to escape.

There’s nothing special about Tommy, nor about Fionn Whitehead, the actor who plays him. He does nothing spectacular at all throughout the film, and yet he does the one most spectacular things of all, he survives. Dunkirk isn’t a war movie, in a sense at least. It has more in common with survival or even disaster films. It’s essentially a series of situations, told in different time patterns, coming together to form a narrative whole. The plot involving the soldiers on the beach, all of whom we know no more of than their names and some not even that (of course, because that’s the point), takes place over an entire week. If we consider their time spent at Dunkirk, that’s hard to believe. That is, unless we factor in the trip home by boat and then by train.

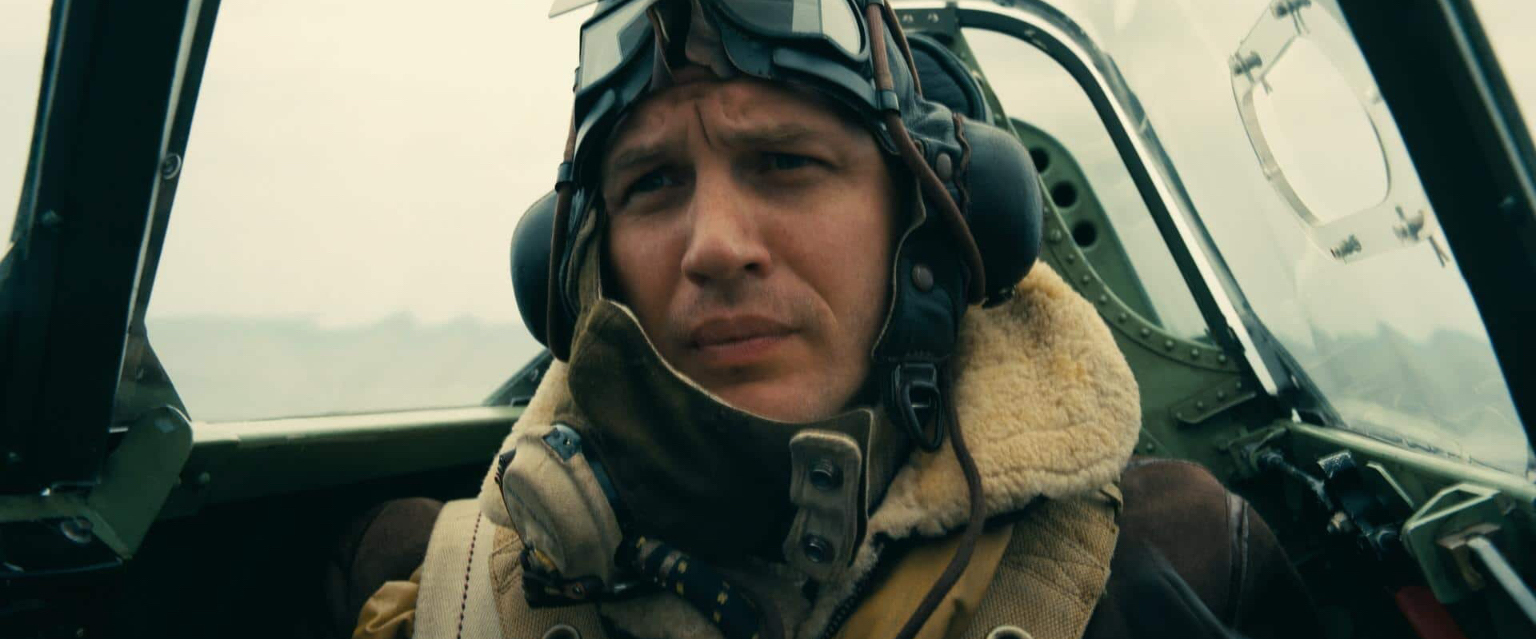

Two more subplots fill out the film’s brief runtime. One of them, by air, stars Tom Hardy in the cockpit of a British fighter plane trying to clear the skies despite being severely outnumbered. These scenes are a pure joy, tense and exhilerating. Hoyte Van Hoytema, following on from his role as cinematographer on Christopher Nolan’s previous film, Interstellar, makes full use of the IMAX cameras at his disposal and some of his best work is on display in the aerial sequences.

The other storyline takes place down at sea. The call has gone out and one man, that man’s son, and a boy named George head out from Dover in their small boat to do what they can for the men trapped at Dunkirk. Mark Rylance spells out one of Nolan’s points for us; why should men his age dictate war, but then stay at home while their children fight and die? They pick up a traumatized soldier stranded alone in the ocean. The horrors of war have affected him deeply. “Is he a coward?” asks George. It’s a frustrating line to hear. In fact, George is a mostly frustrating character. He means well, but his role in the film lacks the impact it so desperately needs.

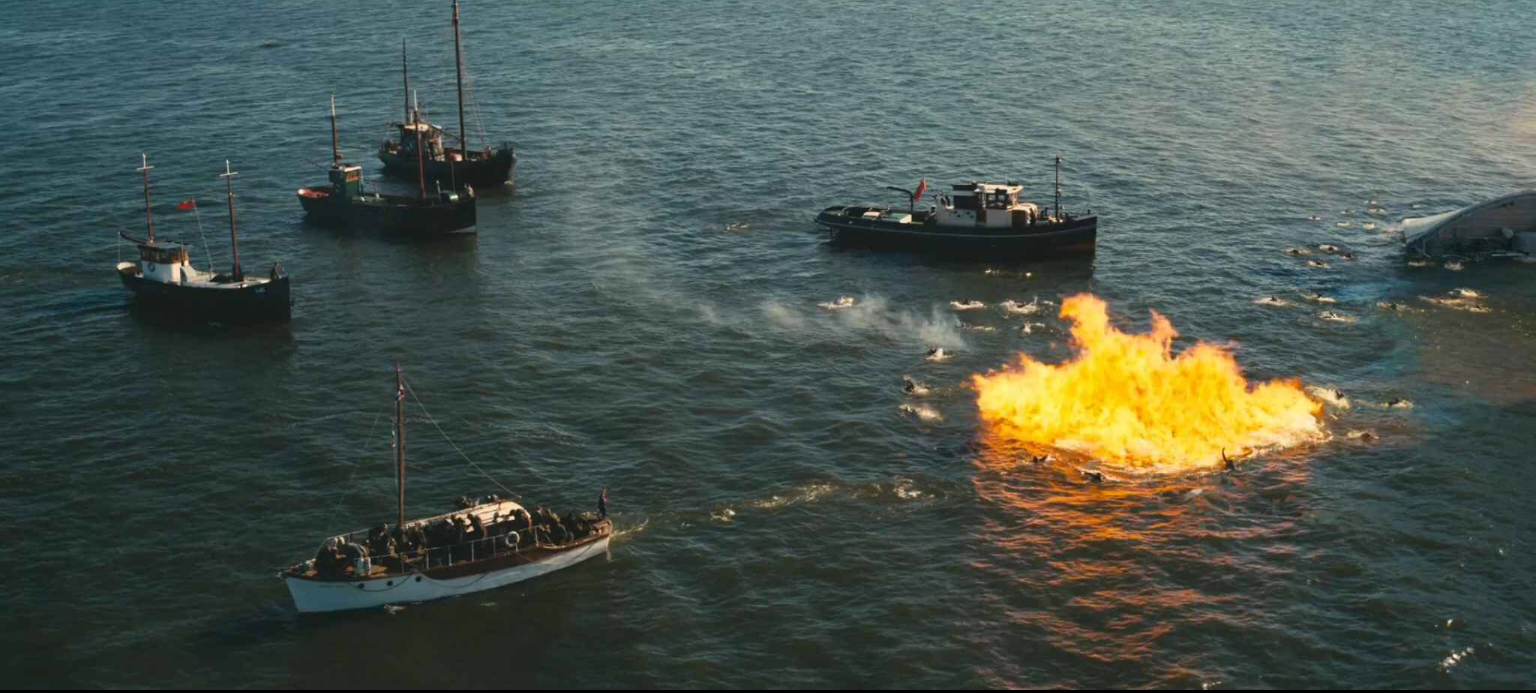

There’s actually very little fighting here. The stranded soldiers are only ever trying to avoid “the enemy,” a faceless adversary we never get a glimpse of except by air. It adds to a feeling of helplessness, of being boxed in. The enemy is everywhere, and we can’t see them. When the bombs are dropped, the film’s sound design becomes an essential cog. The screams of dying soldiers when the Destroyer goes down is an obvious example; the sound of the sand falling back down to the ground and covering Tommy after a beach assault is just as poignant. Hans Zimmer’s soundtrack is perhaps his least ever likely to make for satisfying standalone listening; it’s perfectly suitable for Nolan’s film. A ticking plays in the background for a good chunk of time, adding a sense of urgency. Everything is a frantic mess, and yet the music is so precise. It swells when the small boats arrive at the beaches of Dunkirk, and the characters, including Kenneth Branagh as Navy Commander Bolton, are given a rare opportunity to smile.

While on the beach they get a small reprieve. A vessel under fire floats out to sea shortly after the tide comes in. Below the deck, Tommy, Alex (Harry Styles, impressive against all expectation), and a small company of boys bicker and battle for survival. They abandon ship, and we float into the final act. The three timelines join up for a brief moment at this point, and though it’s nicely structured it fails to have a profound effect in the same way that Nolan’s previous films have had as a result of his time-obsessed screenwriting. It’s the shortest film of his career, unless we count his no-budget 1998 film Following. And yet it really couldn’t have been any longer, either. It’s also incredibly sparing with its dialogue.

Dunkirk is about experience. Nolan wants us to feel the trauma, the isolation, the destruction. In this sense, it loses something in the transition to home media. The film is built around empathising for the boys and men trapped in a horrifying situation. It is less powerful on repeat viewings, and yet still engrossing. It’s hard to learn more from what little the film gives, and it’s not a feeling we need reminding of. Yet its ending remains powerful and moving, victorious and yet equally as somber. We know what happens next, but the characters do not. Alex believes that they failed their country, a heartbreaking footnote to their survival. For the most part though, this is a technical marvel that often lacks heart.

The film ends on two images, the second one being rather abrupt. The first is of the pilot’s burning plane. The second, a brief glimpse before we cut to black is of Tommy, blank-faced, looking straight on. He’s our main character. He’s also every character. Some die, some survive. There’s no victory, but some solace. And there’s a future, at least for him. An anti-war sermon as much as it is a love letter to those that survived and those that died on the beach at Dunkirk, and a visual cinematic achievement certainly worthy of your attention.

Film ’89 Verdict – 7/10