Heat (1995).

The film by director Michael Mann that many of his fans would consider to be his Magnum Opus, brought together the two biggest actors of a generation as well as an outstanding supporting cast. Does it still hold up after 23 years? The short answer is a very assured ‘yes’.

1995 was, on reflection, a great year for film. A number of classic, genre defining films were released that year. The historical epic was resurrected with Braveheart, and innovative thrillers and crime dramas looking at the subject from various angles wowed viewers with a degree of style and flair that would likely make Hitchcock swoon. David Fincher’s Seven, Bryan Singer’s The Usual Suspects, Martin Scorsese’s Casino, all were both stylish and thoroughly entertaining and have become well deserved classics. There is another to add to that illustrious list, Michael Mann’s Heat, a remake of his 1989 TV movie L.A. Takedown.

“All I am is what I’m going after.”

If one were to think of the crime drama in terms of the perspective it takes, then I can think of no more balanced a viewpoint than Heat, which portrays both the criminals and police with no particular bias. Whilst this is more stylised stuff than recent crime dramas such as TV’s The Wire, with its uber realism, Heat is no less entertaining.

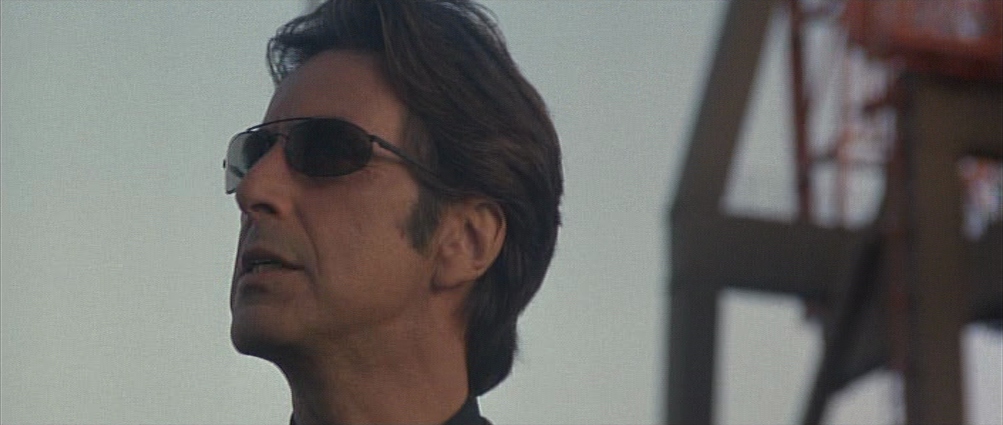

Heat tells the story of a gang of professional bank robbers – to call them merely bank robbers seems somewhat remiss, they really are consummate professionals – led by the icy cool Neil McCauley (Robert De Niro). McCauley has surrounded himself with men who excell at their specialist tasks, men who he trusts and who would never break that trust even if they got caught by the authorities. He chooses jobs based on information provided to him by Jon Voight’s Nate and Tom Noonan’s technical wizard, Kelso. He follows a strict code of ethics – although his chosen profession, by its very nature, is anything but ethical – and exudes a fierce level of discipline which makes him highly efficient at executing complex heists.

It’s only when unexpected changes to his otherwise meticulous plans cause McCauley to rely on help from men outside of his circle of trust, that he loses complete control over his team. One such unknown quantity is Waingro (Kevin Gage) who is taken on at last minute as an extra body in the cash-in-transit van heist that opens the film. Unlike McCauley’s regular team, Waingro is a borderline psychotic who kills a disarmed security guard resulting in McCauley’s quick decision to leave no witnesses to a robbery that’s quickly escalated into an execution. When the men later meet to split their earnings, the group miss their opportunity to dispose of the dangerous wildcard Waingro and he escapes into the L.A. night. This is crucial setup to events that will permeate the entire film and the planned robbery that became a multiple homicide attracts the attention of another group of professionals.

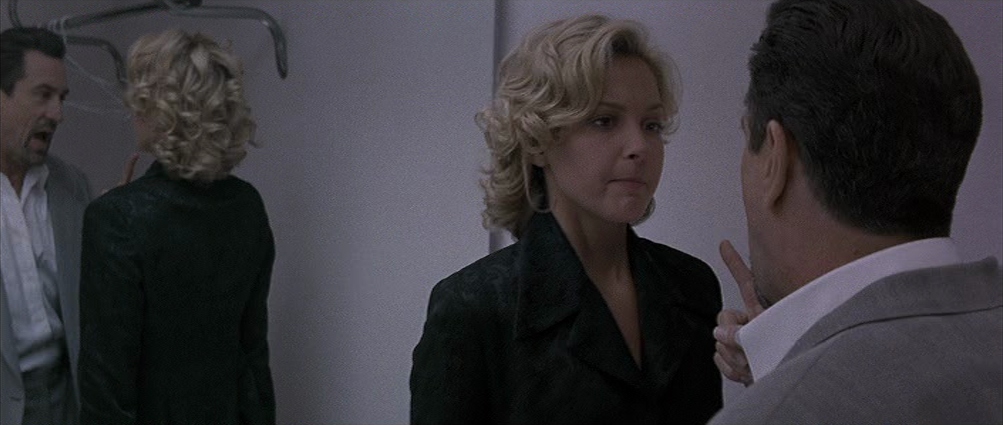

This second group isn’t another group of thieves wanting to muscle in on the action. No, this film of two halves, two sides, tells of diametrically opposed forces of law and order versus criminality. We’ve seen the criminals and their actions have now caught the attention of the LAPD’s Robbery-Homicide Team led by Vincent Hanna (Al Pacino) a man who, like McCauley, excels at his chosen profession, and more than that, understands and respects the nature of his quarry. So driven is Hanna, so obsessed with his job is he that his personal life is in tatters. His partner, struggling to bring up a teenage daughter from a previous relationship (a superb Natalie Portman) sees him fleetingly and when they’re together she feels that he’s carrying baggage that gets in between their ability to be a “normal” family.

It’s the sheer amount of time and effort that Mann takes to flesh out not only his two main characters, but that of the men on each man’s team that gives a level of depth to Heat that sets it head and shoulders above any other film in the crime drama genre. We see an almost vignette style of storytelling at play where characters that would get scant character development in any other similar film are given a significant amount of extra screen time. Characters like Dennis Haysbert’s getaway driver Don Breedan is shown to be struggling with a job working in a kitchen with a boss who looks down on him, mistreats him and makes threats to report Don to his parole officer should he respond with insolence. The offer of joining McCauley’s gang seems like his only option, we see the cause of persistent reoffending but never does Heat preach or get bogged down by overly political or social commentary. This is a tight, lean piece that gives focus to its characters first and foremost in spite of its considerable, almost epic runtime.

The cast Mann assembled with Heat is the stuff of dreams. Yes, Pacino and De Niro have been in the same film together (The Godfather Part II) but not opposite each other, and no screen time was shared. Both actors were (at the time at least) arguably the greatest actors of their generation and seeing them put in such measured, nuanced performances was a thing to behold. There was no sense of behind the scenes one-upmanship like that of Steve McQueen and Yul Brynner in The Magnificent Seven. This was the very definition of mutual co-operation between two seasoned pros, each actor bringing both aspects we’d seen before (Pacino’s shouting intensity, De Niro’s cool menace) as well as a sense of passion for this particular piece. They are both thoroughly convincing as experts in their respective fields, meticulous criminal and determined cop alike.

The huge supporting cast makes for mouthwatering reading: Val Kilmer, Jon Voight, Natalie Portman, Tom Sizemore, Ashley Judd, William Fichtner, Tom Noonan and Danny Trejo to name but a few. Even the most minor roles are occupied by familiar faces: Jeremy Piven, Martin Ferrero, Xander Berkeley and Hank Azaria amongst many others. It’s an exemplary cast an every single one of them put in at worst, admirable performances, at best, electrifying.

“You do what you do and I do what I gotta do.”

One of the films’ greatest and most memorable scenes is the coffee shop confrontation between McCauley and Hanna. Any other script would have upped the antagonism between the two leads, but here both men aren’t too macho as to withhold their obvious respect for one another whilst still holding on to a degree of threat and menace should one get in the way of the other. The relatively brief chat is nothing short of mesmerising, and their only real conversation in the 170 minute runtime. It’s perfectly scripted and both actors delivery and commitment to the scene are remarkable. To have been there watching this monumental scene being filmed would have been the stuff of dreams and behind the scenes stills show that Mann was intimately involved in guiding both actors. Every line of dialogue has its place. Nothing is wasted, there is no fat on the meat.

“I mean is this guy something, or is he something? This crew is good.”

Technically the film is a marvel on every level. From Dante Spinotti’s icy blue cinematography to Elliot Goldethal’s mournful score and no less than a four man editing team, Heat is a joy to behold. Some may argue that the film is a little long, but I feel this gives the film an extra layer of depth as even minor characters such as Dennis Haysbert’s aforementioned getaway driver who gets his own almost self contained mini story arc thanks to the generous runtime. Some of the dialogue, Voight’s in particular, is difficult to understand and riddled with some quite baffling jargon (a problem that would later cripple Mann’s Miami Vice for many), but this is a very minor gripe.

One can’t discuss Heat’s technical merits without mentioning the films other standout scene, the now legendary bank heist/shootout. The tense build up of the stunningly executed heist leads directly into a lengthy, brutally realistic and ballistically correct gun battle in L.A.’s busy financial district. With no score and the actual real gunfire sounds used as they were recorded on the day this truly is a shootout like no other. It’s extended runtime and flawless depiction of geography makes the action easy to follow, helped by some textbook editing. So good was the scene in fact, that in 2003 it was used as part of a special forces training package illustrating textbook cover & move tactics. In particular, actor Val Kilmer’s ability to rapidly cover, fire and reload looks instinctive, like he’s an experienced soldier, not a Hollywood actor.

Aside from the more famous, grandstanding scenes that Heat is known for, there are innumerable smaller, seemingly less consequential scenes peppered throughout Heat that serve as a microcosmic example of the deft hand employed by Mann in every facet of the film from production design, the choice of filming location, to the carefully considered dialogue. One such scene is when McCauley and Kelso (Tom Noonan) meet at Kelso’s home to discuss the plans to a bank robbery that the latter is effectively putting up for sale. On paper this could have been a moment that conveys mere exposition, but there is much to appreciate in this brief but important scene. The performances are spot-on; De Niro questioning and testing Noonan’s plan as he searches for potential flaws; Noonan’s uncontrolled excitement as he explains how he plans to circumvent the bank’s security measures. Particularly satisfying is the exchange when Noonan shows De Niro a printout of the bank’s cashflow and the latter asks, “How do you get this information?” Noonan’s reply, “It just comes to you. This stuff just flies through the air. They send this information out. I mean, it’s just beamed out all over the fucking place. You just gotta know how to grab it. You just gotta know how to grab it.” De Niro’s double take at Noonan’s answer is subtle but effectively conveys the fact that his caution causes him to question and evaluate every facet of this most dangerous lifestyle he’s accepted.

The techniques deployed in this scene are equally unflashy yet brilliant. The shot that opens the scene, a two-shot of the characters, is a slow, almost imperceptible, zoom-in. It’s a minor technical flourish that adds significantly to the quality of the scene and is helped by some great production design and choice of location which do much to reinforce Kelso’s character, especially as he only appears in this one scene. Kelso’s home is crammed with all manner of technology and is equipped with a multitude of satellite dishes, so that he can “grab” all the information that he’s looking for. His house is also situated on an elevated plateau, ideal for transmitting and receiving said signals. The attention to detail is staggering.

Mann and Noonan had previously worked together on Manhunter, in which he played a terrifying serial killer, a character light years away from Kelso. It’s something of a common reoccurrence that Michael Mann often casts the same actor in more than one of his films, playing completely different types of character; Wes Studi in The Last of the Mohicans and Heat, Jon Voight in Heat and Ali, Jamie Foxx and Barry Shabaka Henley in Ali, Collateral and Miami Vice.

Another example of Mann’s carefully considered approach to building a believable world in which his multitudinous characters operate is the scene where McCauley finds himself embroiled in a double cross by the duplicitous Roger Van Zant (the ever reliable William Fichtner). With McCauley under fire, he’s saved by the security measures he’s put in place in advance, namely his friends Chris Shiherlis (Val Kilmer) and Michael Cheritto (Tom Sizemore) who make swift and accurate work of the hitmen who are trying to kill their boss. As Michael shoots the driver of the hitmen’s pick-up truck at the end of the scene, instead of him typically losing control and crashing the truck in a gratifying ball of flame, the vehicle just slowly and almost innocuously, almost gently even, drives into a nearby wall causing minimum noise. It’s this deviation from the established norm, the level of heightened movie realism we’ve become so accustomed to, that raises Heat head and shoulders above its many counterparts in the crime thriller and action film genres and shows this to be the masterwerk of a director who truly knows his craft and how to add a level of polish to his films that is almost consciously imperceptible. It’s a small moment but speaks volumes of his ability.

The real beauty of the story Heat tells is how each constituent part helps build towards an incredibly satisfying and organic conclusion based on the established traits of our protagonists. McCauley is the consummate perfectionist but the one error of judgement he makes early on in allowing the psychotic Waingro to first join his team and later failing to dispose of him, will come to be his undoing. We see through Hanna’s side investigation of the ‘8 Ball Killer’, none other than Waingro himself, that this man is more than a thief, he’s a cold blooded murderer who is later hired by Van Zant to take out McCauley’s team. When he cruelly and brutally kills Trejo’s (Danny Trejo) wife and leaves Trejo for dead, this is crossing a line that goes against even McCauley’s moral code. When he later has an opportunity to exact revenge on Waingro he goes against his practice of strict discipline and lets emotion override his usually methodical nature.

It’s the successful interweaving of the myriad essential subplots that enriches the grand narrative of this epic tale. The city of Los Angeles is an intrinsic element, more than a mere backdrop to the events, L.A. itself almost feels like a character vital to the overall feel of Heat. Even the film’s title – derived from McCauley’s mantra of never letting himself get attached to anything he’s not willing to walk away from if he feels the heat around the corner – is perfectly tailored simplicity and apt to the proceedings.

“We’ve been face to face yeah, but I will not hesitate, not for a second.”

Heat’s influence is still being felt today and was beautifully paid tribute to in The Dark Knight’s opening prologue (in fact elements of Heat permeate the whole film). It featured two of Hollywood’s greatest actors giving Oscar worthy performances surrounded by a vast and superb supporting cast and talented crew. Movies like this sadly come far too infrequently, movies where every facet is so tightly constructed with such care and attention to detail that the finished product is indeed, as the director intended, and as the tag-line so accurately puts it, an epic tale of crime and obsession.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 10/10

Film ‘89 would like to thank Tony Sower for his contribution to this article.