Thief (1981).

Whilst effectively using existing and sometimes generic cinematic tropes, the films of Michael Mann could easily be a sub-genre unto themselves. Stylish peeks into the criminal underbelly focusing on hard, tough men who are sometimes impeded by their own psychological complexities. Mann makes thrillers which, when they’re at their best, are more interested in the character traits of the protagonists than they are the central story. He has in fact, been accused of telling the same story over and over again with different characters but this isn’t entirely fair.

For Mann, the attraction is not the story, it’s the character, it’s the man (for it is inevitably a man) at the heart of it.

The origins of this obsession with flawed masculinity can be traced back to his feature directorial debut, Thief (1981), a film that many still consider his best work. It tells the story of Frank (James Caan), a professional thief who is trying to achieve a version of the American Dream in a way that only a career criminal can do. There is little room for niceties, just sheer determination. He’s not interested in subtlety, instead employing a directness that borders on hostility. His philosophy is a simple one, if he wants something he goes out and gets it, consequences be damned.

Frank decides to get married so he goes out and gets a wife, ignoring any objections she may have. Initially Jessie (Tuesday Weld) is somewhat reluctant, especially after Frank appears two hours late for their first date but he’s not interested in her objections. He just grabs her, forcibly removing her from the bar she had been waiting for him in, pointing a gun at whoever complains about his treatment of her. His approach is not exactly romantic but it’s straight to the point.

He is equally direct at work. When he is threatened or double-crossed, he deals with it himself, revealing the dichotomy at the centre of his personality – a cautiousness and thoughtfulness that has helped him become so successful and a recklessness that seems to border on suicidal at times. In one scene he loses money when an associate (his fence) is thrown out of a window, so he goes to the man he suspects is responsible and demands the money he lost. He takes precautions – a gun and a getaway driver – but then barges into an office, terrorising the women working there and threatening the suspect. He’s not there to talk but to threaten, which makes a mockery of his carefully laid plans and preparations.

When Frank is double-crossed by the local mob boss, Leo (Robert Prosky) he holds back no punches – he tells him his position, making demands without thought of consequence, without acknowledging who he is talking to and the potential repercussions.

It is this duality that makes Frank such an interesting and complex character. He may seem to be in control at all times but is in fact being controlled by his emotions. He can’t see this but it’s obvious to us, the audience, and to his potential enemies who see it as a way to manipulate him.

In Mann’s 1995 film, Heat, Robert De Niro’s character Neil McCauley’s mantra is “Don’t let yourself get attached to anything you are not willing to walk out on in 30 seconds flat if you feel the heat around the corner.” Frank has a similar philosophy which he developed in prison and as a child being brought up in various orphanages and foster homes – don’t get tied down to anything. Yet he desperately wants to settle, to live an ordinary life. He doesn’t see the conflict between these two perspectives but again, we can.

This is a flaw that is open to manipulation and that is exactly what Leo does. After Frank rebukes Leo for suggesting this pay should be invested into the ‘company’ (which would increase the mob’s grip on Frank), Leo changes tack and offers to help Frank and Jessie get a child (they can’t adopt because of Frank’s criminal past). Frank jumps at the chance, ignoring the entire preceding conversation and the threat of Leo’s control. This of course, is going to be used against Frank later. We can see it, Leo can see it but Frank can’t as he’s too emotionally involved. He can only see what he wants to see – his dream of family life.

What makes Thief so interesting is that although it has all the ingredients of a thriller – the Mob, guns, a heist – it is really a complex character study. It’s all about Frank and the pay-off, the explosive finale that one expects with such thrillers, is dictated not by plot but by character. How Frank reacts to this manipulation and control dictates the outcome, not a twist or storyline. This is the strength of the film – whatever happens feels psychologically true to the character at the centre of the story the film is telling.

One scene perhaps reveals more of this complex character than any other. It’s a deceptively simple scene with Frank and Jessie in a diner, sitting across from one another. Frank tries to convince Jessie to be with him, to buy into his dream for the future. He shows her a collage of images cut out from magazines he had made in prison which summed up what he wants out of life. On the surface it resembles the legendary meeting of De Niro and Pacino for the first time on camera in Heat. There the cop and the robber discuss their respect for each other and their willingness to take their pursuits all the way, to wherever end that may lead. They are articulate and focused.

Frank is not an articulate person, especially when trying to discuss themes and aspirations that he has little experience of. His monologue is rambling, he repeatedly hesitates and mumbles but this only seems to add to his determination and reveals so much more about the man he really is. Jessie’s response is similar – they are the same person and want the same thing. It is a beautifully acted scene by both Weld and Caan, who considered the scene the best of his career.

Mann’s first film (the made-for-TV, The Jericho Mile) was filmed in Folsom Prison and Mann has said that this experience gave him a glimpse into what Frank’s time inside would have been like and what could have molded him into the character he became.

Michael Mann is almost the definition of a auteur filmmaker and if he has any antecedents from the golden age of cinema, it could well be Howard Hawks. Although Hawks was proficient in a wide range of genres, he was often attracted to stories about flawed men, often struggling in relationships with women and other men. Mann’s women are not as tough as Hawks’, mainly because they are rarely invited into the man’s world, but the men – with they dedication to their craft, their willingness to step on toes and their loose attitude to rules, laws or established practice – are undoubtedly the natural heirs of Hawks.

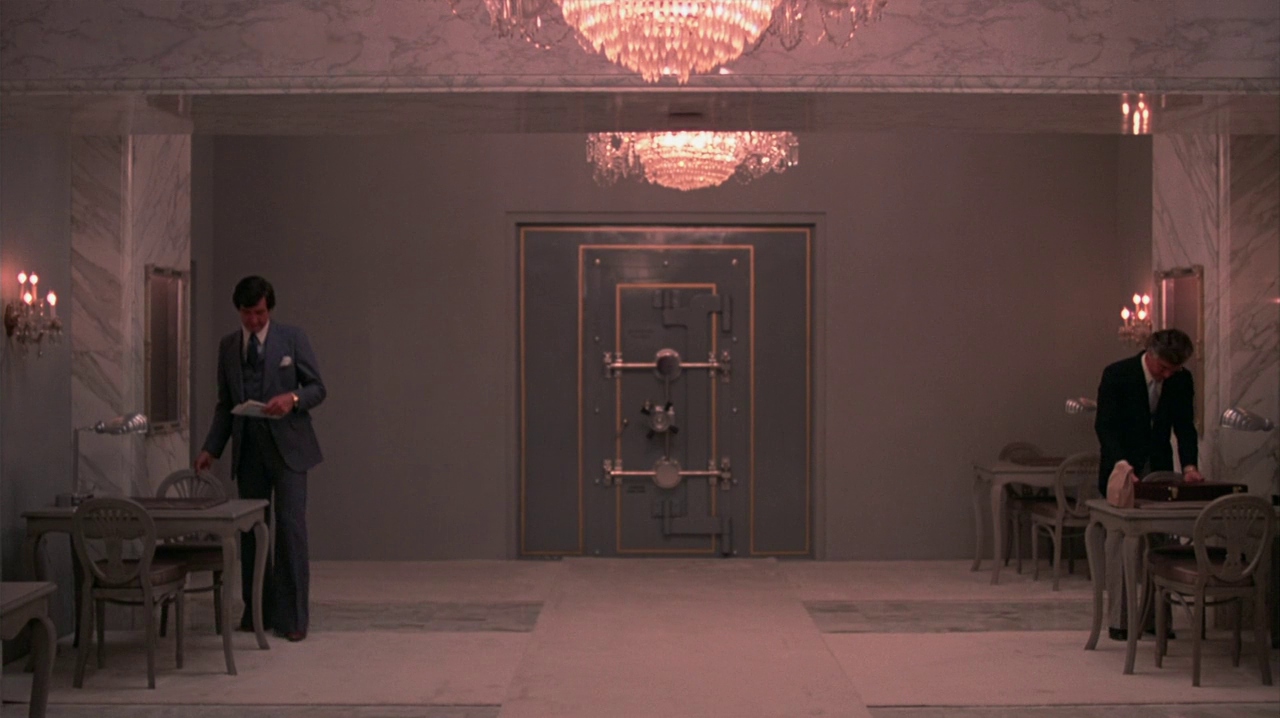

Thief is a beautifully made film with some stunning photography, especially the city at night, a Mann specialty – see his 2004 film Collateral which manages to capture the night-time spectacle of Los Angeles like no other film ever has until maybe Dan Gilroy’s stunning Nightcrawler ten years later. The safe cutting scenes are particularly pleasing on the eye, the contrast between the dark rooms and the sparks from the saws works so well.

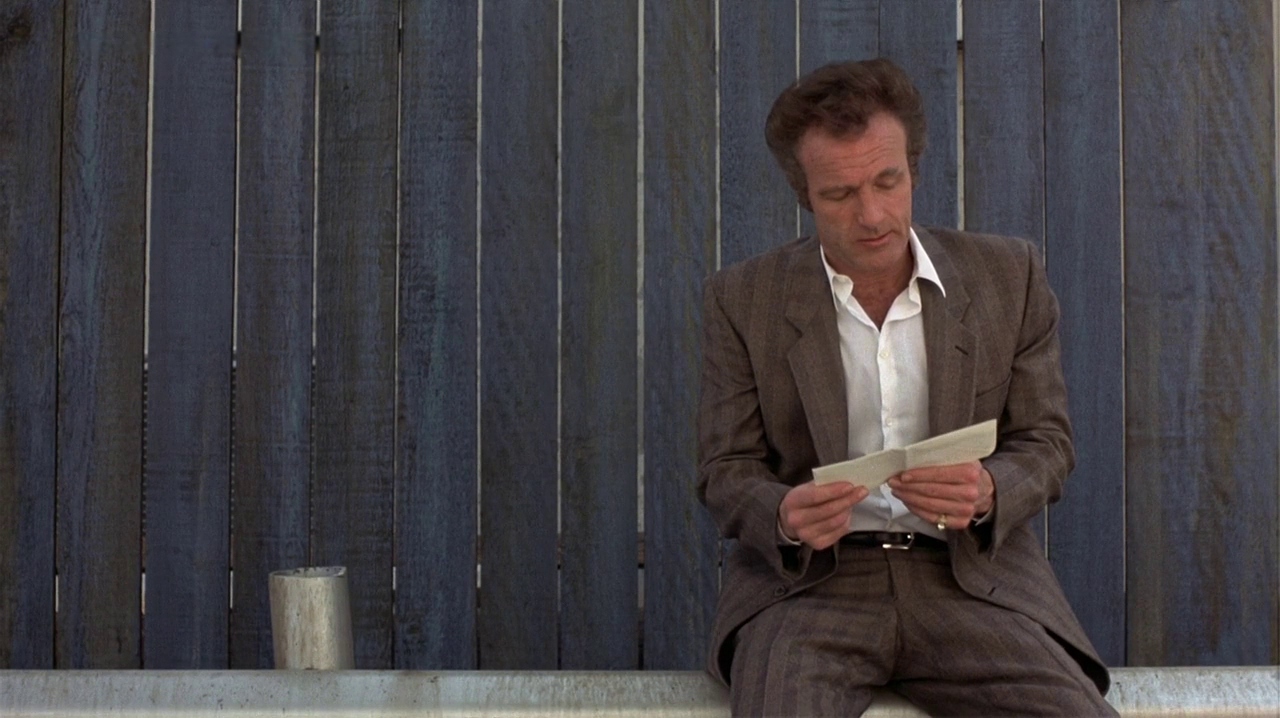

But despite the stylish photography we also get a sense of the very real work involved. This is not an easy job, it is manual labour and each stage of the operation, although almost wordlless, is punctuated with grunts and murmurs. The effort is palpable and arduous. Frank and his partner Barry (an almost monotone James Belushi in his first role) have done this countless times before. They know exactly what needs to be done and do it with expert efficiency. When the job is complete, Frank sits back and smokes a cigarette, a look of exhausted satisfaction on his face. As I watched I couldn’t help but make comparisons with the industrialisation in the opening scenes of Michael Cimino’s The Deer Hunter. This is not glamorous, it’s a blue-collar heist film.

The performances are excellent throughout, but special mention has to be made of Robert Prosky (in his first film) as Leo. Before watching Thief I only knew him from playing the drunken letch in Mrs Doubtfire, the kindly cinema usher in The Last Action Hero and the slightly crazy vampire/Late night TV host in Gremlins 2: The New Batch, none of which prepared me for this manipulative mob boss with a truly vicious streak.

“Ya kids mine because I bought ‘it. You got ‘im on loan, he is leased, you are renting him. I’ll whack out ya whole family. People’ll be eatin‘ ‘em in their lunch tomorrow in their Wimpyburgers and not know it. You get paid what I say. You do what I say, I run you, there is no discussion.”

Blues fans (as I myself am) will see a brief scene of The Mighty Joe Young Band playing in a bar and there is a scene missing from the final cut but well worth looking up on YouTube which includes a part for the late great Willie Dixon. Initially, Mann had wanted to score the whole film with classic Chicago Blues but changed his mind, going with Tangerine Dream instead as he thought their electronic music was more suited to Frank’s personality. The score certainly does fit the film but I would have loved to have heard the original soundtrack as I think a bit of Muddy Waters, Little Walter or Howlin’ Wolf would have really added to the atmosphere. Ironically the film was nominated for a Razzie for Worse Musical Score that year.

Rounding out the cast is Willie Nelson as Frank’s mentor and an early appearance by Dennis Farina as one of Leo’s men. John Santucci, who had a brief role as a corrupt cop, also acted as a technical adviser on the film and was himself only recently paroled for doing the same job as Frank. William Peterson, who would later appear in Mann’s adaptation of Thomas Harris’ Red Dragon (the first on-screen appearance of Hannibal Lecter) appears briefly as a bouncer in a night club.

Thief was co-written by Frank Hohimer (whose real name was actually John Seybold) a career criminal who wrote the book The Home Invaders: Confessions of a Cat Burglar upon which the film was based. It was originally titled Violent Streets and the decision to change the title was the right one. Thief is not a story about social problems or multiple characters like, for example, The Warriors. The focus of the film is one man who is both defined and limited by his occupation. It is an insular story that isn’t interested in the wider criminal underworld. Even Leo’s mafia links aren’t explored as they aren’t pertinent to the story being told or the character that’s being explored. Frank wouldn’t be interested, neither should we.

Thief is a film well worth going back to. It’s meticulously crafted, as is the expected norm with a Mann film, it has great complexity, brilliant performances and spot on direction. Much of the stylistic flare on show here will be further developed in Mann’s later films of which Heat is probably the closest in terms of style and themes. Whether Thief is as good a film as Heat is a debate I won’t go into here. Either way it’s a stunning theatrical debut that gets my absolute recommendation.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 9/10

Thief is available on Blu-Ray in the U.S. from Criterion and in the U.K. from Arrow Video.