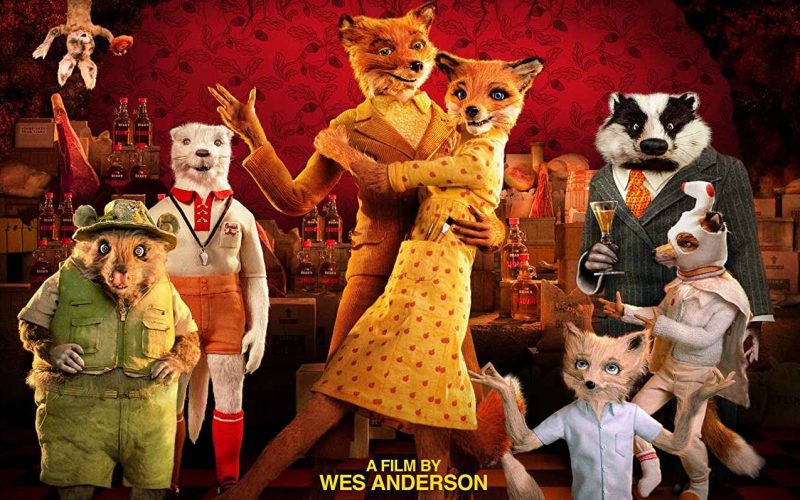

Fantastic Mr. Fox (2009).

With his 2009 animated hit Fantastic Mr. Fox, Wes Anderson makes the process of adapting Roald Dahl’s story into three acts sound effortless. Dahl had provided the middle of the story, but there was still a beginning and an afterwards that was, apparently, begging to be told. So Anderson told it. He told it with puppets and still cameras and closed sets, and he recorded his audio in forests, in attics and in stables. It was, as Anderson describes it, a spontaneous endeavor.

Mr. Fox isn’t really a good husband or father. The former is clear almost immediately, when he asks for his wife’s opinion but then disregards it for his own, more favourable choice. He decides that instead, his way is the better one, but he’d decided that before she even answers. This isn’t to say that it stands out that he’s a bad husband or father, the latter of which we’ll learn more about later. Anderson’s films all have a way of throwing a veil over complex human behavior with a sense of adventure and with tongue firmly in cheek. And yet, veil or no veil, those characters and their issues are very intentionally there for us to see.

And so, Mr. Fox, despite his very apparent intelligence, begins making some very stupid decisions. One moment he’s making an educated assumption about the position of a fox trap overhead that turns out to be a potentially fatal error. The next he’s deciding to steal from three wealthy and very dangerous farmers despite a promise he made to his wife the day she revealed that she was pregnant. His need to be mischievous and cleverer than everybody else is a dangerous trait.

Plotting to steal from Boggis, Bunce, and Bean dooms both Fox’s family and all of the neighbouring animals, forcing them deep underground while the farmers deploy their combined workforces to try and either starve them out or blow them to pieces. The story is, at its most fundamental, about Mr. Fox seeing the error of his ways and being forced to hatch a plan that will get him and his companions out of a terrible situation.

It seems so obvious that Anderson’s first foray into animation would be stop-motion. His meticulous, neurotic attention to detail is a perfect fit for an art form that demands such patience and care, and the production design on the film might be its highlight. The whole thing has a comforting warmth to it. The puppets themselves are spectacularly rendered, and the framing is as precise as in any of Anderson’s pictures.

There’s so much energy running through the film’s brisk ninety minute runtime. Anderson and Noah Baumbach’s script is buzzing with obscure humour, and its characters are designed both on paper and physically with quirky and distinct personality. Alexander Desplat’s soundtrack is a riot, inspiring spontaneous dance sequences and giving aid to the film’s bouncy action. The characters are unusual, but they aren’t shallow. There are few memorable character dynamics, but they are all expertly crafted.

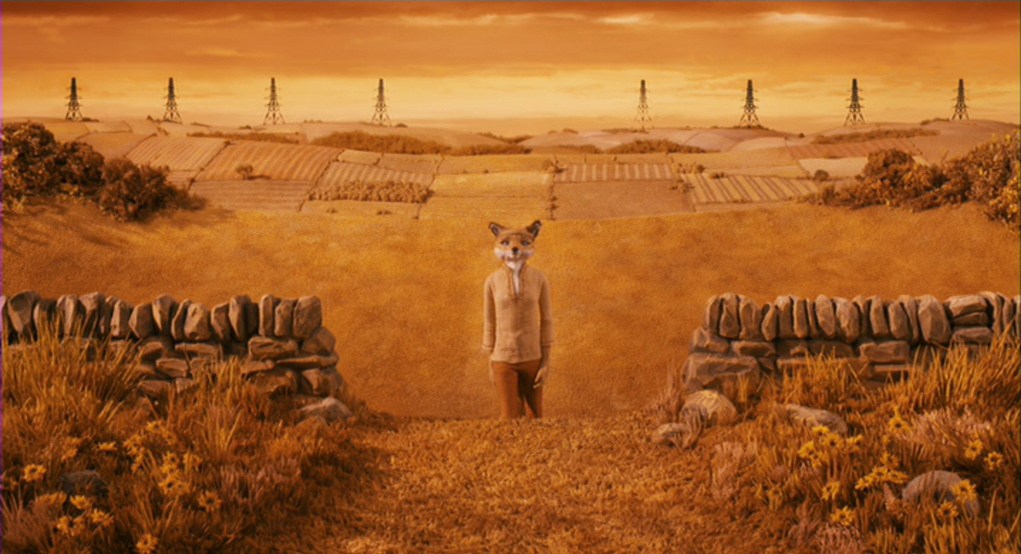

Anderson takes a relatively generic premise and, channeling some of the same creative flair as Dahl himself, infuses it with charm and presence, building a script that buzzes as though running on caffeine. As much as Mr. Fox is expected to better himself in some glaring ways, a more overt theme might be that one must learn to embrace their natural instincts in order to achieve self improvement. In its closing moments, Mr. Fox shows very clearly that he is still the same thieving, conniving fox, far too smart for his own good, but he channels it in a way that can benefit his loved ones rather than harm them.

Ash, his son, toes the line between nuisance and hilariously pessimistic. Jason Schwartzman gives a pitch perfect performance as Ash, with some of the film’s funniest lines, and the relationship between he and his cousin, Kristofferson (Eric Chase Anderson), is one of its best. George Clooney is predictably fantastic as the titular character, while Meryl Streep voices Mrs. Fox, a strong-willed and loyal companion who sticks by her husband even if her faith in him wavers.

The film dives into rare emotional territory when the two of them have a deeply honest conversation about their marriage, with Mrs. Fox exclaiming that she should never have married him. The two are calm, and there’s a lot of love there. It’s ironically a deeply human moment. Similarly, Mr. Fox shows Ash affection for the first time later on. These are moments of quiet beauty thrown amidst the chaos.

Anderson’s films all tend to have an undercurrent of sentimentality and a sobering sense of identity. It’s easy to overlook this and I think that’s the way it’s intended. His films aren’t trying to make a profound point, but by their very nature they show us the best and worst of people (and, as it so happens, Foxes). There’s more to explore with Fantastic Mr. Fox if we start to think about the way they dress, the way they act, the way they feel. One of these things almost always contradicts another.

For one, they all dress like civilians. But then they scoff down their food like wild animals. Mr. Fox is afraid of wolves; he says so on many occasions. Is he afraid of the wolf, or does he simply dislike his own savage nature? Near the end, the characters come across a wolf as they escape from the farm. It’s a scene brimming with beauty and peculiarity, but also with so much subtext.

Fantastic Mr. Fox is strange because it can be strange. It’s also both tender and turbulent when it wants to be, and it more than fulfils its role as both an adaptation and a piece of work in its own right. Its cast delivers, and its characters are rich and full of life, but it’s the look of the film that defines it. In a film told from the perspective of domesticated and yet undeniably wild animals, it has as much warmth and heart as any other. Stop-motion is sadly a scarcely used art form these days, and maybe, for that reason and others, Fantastic Mr. Fox will continue to thrive as a shining example of this near lost method of filmmaking.

Film ’89 Verdict – 8.5/10