“From a Certain Point of View”, Examining The Politics of The Star Wars Saga.

To paraphrase Toni Morrison, All good art is political. The Nobel and Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist was, as she put it, not interested in art that is “not in the world.” That is, all art that is worthwhile is of the world and the people in it, and is therefore political.

I bring this up because much of the discussion around the Star Wars sequel trilogy has centered on the politics of Star Wars and whether or not the franchise has any business making bold political statements. I contend that Star Wars has been making political statements since A New Hope and all through the prequels. While the sequels may have their own political messaging, the effectiveness of those messages has become muddled and made indecipherable due to late-stage changes in direction (as well as director), but most of all, because of the interests and input of the Disney corporate machine. The Star Wars films written, directed, and/or produced by George Lucas, whatever their faults, were consistent in their anti-fascist metaphors, as well as commentaries on the evolution and subsequent downfall of democracies. Disney has little interest in such messages, and if the filmmakers under their employ do, they are occluded by the circumstances surrounding the making of the films and the powerhouse industry behind them.

To say that “all good art is political” is not to say that all good artists sit down to compose their work with a definite political intent. JRR Tolkein, for example, did not write The Lord of the Rings as a commentary on the perils of 20th Century technology, but the scourging of the Shire by Saruman at the end of The Return of the King, turning this idealized late-19th-Century fantasy of idyllic English village life that was Hobbiton into a polluted, coal-dust-encrusted hellscape, is a parallel to Tolkien’s own life, his own England, that cannot be overlooked. Parallels to Tolkien’s personal experiences are everywhere in The Lord of the Rings, from his incorporation of his Christian philosophy into the foundations and creation of Middle-Earth, to his love of languages and myths, to his fascination with ancient Nordic civilizations, as well as Anglo-Saxon and pre-Anglo Saxon Briton. All this before we look at how his World War I experiences colored how he composed The Lord of the Rings, with his Hobbits, simple shire-folk, traveling across the fire, violence, and gear-ravaged Mordor and the plains of Gorgoroth to toss a tool of Men, a scion of pure destruction and evil, into the fire-pits which birthed it, banishing it forever. After which, the participants were never the same, forever scarred and separate from their fellow Men and Elves, Hobbits and Dwarves.

If we were to ask Tolkien if he was a political writer, or even if he composed his Middle-Earth tales as a way to comment on WWI and the terror of mechanized warfare, I’m sure he would say “no,” and then school us on all the mytho-cultural influences that went into composing the languages of the Noldor and Sindar, but that does not mean the work itself isn’t political, and it especially does not negate the decades of context the work has gained since its composition and publication.

Different generations have had time to absorb the work, to look at it in hindsight, and decide what it means for themselves. I’m sure reading about Frodo and Sam traversing the scorched rocks of Mt. Doom has a different resonance for a 9-year-old in 2020 than it does for a combat veteran who has walked across a battlefield rife with bomb craters and corpses. And if the rage of Treebeard and the Ents against the wasteful pillaging of Middle-Earth’s forests by the hands of Orcs and Men, how those villains were devoid of pity or thought of the future, isn’t a political message, I don’t know what a political message is (and an environmental, pro-conservation one at that).

Perhaps Tolkien’s own use of the Ents might be as another symbol of his mourning of the death of the past and the ancient way of doing things, of his own traditional values, being decimated as the speed of life increased during the later years of the 20th Century, but that is still a very stark political message, one deeply held and not conceived of lightly.

So what does all this have to do with Star Wars? Well, that Star Wars was political from the get-go, and that its resonance can be found in unexpected places. George Lucas himself was always a politically aware filmmaker, with his first film THX-1138 being a dystopian nightmare of humanity’s loss of emotion to the cold metal fist of technological progress. A hollow, superficial religion is state-mandated and the expressions of love, creativity, and sexual desire are forbidden. This icy, pessimistic view of the future was a financial failure, but would go on to gain cult status after Lucas’s success with Star Wars.

His next film, American Graffiti, is partly a nostalgia trip, but it was conceived of because the 11 years between when it takes place (1962) and when it was released (1973) contained the assassination of JFK, Martin Luther King, and Robert Kennedy; the Moon Landing, the Vietnam War and the latter stages of the Civil Rights movement. The nostalgia it expressed, after just over a decade, was there because it was of a time when Lucas himself was not affected by the tumult of the world, when his every action was not colored by a war in Southeast Asia. It was 1973 George Lucas reflecting on the naivete of 1962 George Lucas, when he, as a teenager only concerned with fast cars and cute girls and college, could separate his own existence from things like segregation and the Cold War. 1973 George Lucas was no longer so naive, nor was America (or at least the America seen through Lucas’s eyes).

The inception of Star Wars itself was a perfect storm of American cultural influences, the education system George Lucas had access to, and the state of the film industry in the 1970s. Lucas was part of the first generation of filmmakers who actually had the opportunity to go to film school (he, like John Milius and John Carpenter, attended USC). He also had access to the films of foreign masters like Akira Kurosawa and Federico Fellini whose work Americans could see in theaters or in film schools due to their growing distribution in North America. He was part of a generation who could watch old westerns and space serials on television, back-door brain-fuel for what would inspire so much of Star Wars.

Lucas even had direct access to Joseph Campbell and his theories on the Hero’s Journey and the universal mytho-cultural cycle of storytelling (I have my own thoughts on Campbell, but that’s a story for another essay). George Lucas was able to codify all these influences, everything from his practical experience gained from his education, his failures and successes as a commercial filmmaker, his views on mythology and how they can be represented on screen, his love for cinema itself, and translate all of that into this mad space-faring celluloid dream, defying studio executives every step of the way. The mere presumption that Star Wars could be made at a major studio is an act of extraordinary gall and rebellion, and every step Star Wars took towards creation, its rebelliousness grew more brazen. There is no rebellion without political awareness. In this case, studio politics.

But how is the actual CONTENT of Star Wars political? Aside from the fact that any story involving kings and empires and insurrection, from the Arthurian Legends to Game of Thrones, is inherently political, there are intentional metaphors and allegories everywhere. Visual cues like the design of Darth Vader’s helmet being a combination of a samurai helmet and a Nazi helmet, and the Imperial officer uniforms modeled after SS uniforms, are everywhere. Hell, Vader even commands stormtroopers. These are not subtle bits of symbolism. The Empire represents faceless terror and the horror of fascism winning out over humanity. The usurpation of feeling and emotion for technology and material gain. No imperial would ever “reach out with your feelings” because the ideal imperial is a machine, devoid of emotion, carrying out the Emperor’s will with ruthless efficiency.

The average imperial would find a lot to admire about the government of THX-1138. This efficiency is personified in Grand Moff Tarkin, a chilling echo of a colonial governor, casually declaring that the Emperor has dissolved the Senate, that “fear will keep the local systems in line.” He demonstrates the consequences of wielding that fear by destroying an entire planet as a show of force, an example of how far dictatorships are willing to go to maintain control.

What struck me, even as a kid, were the demographics of the unfeeling, cold Empire and the rag-tag hope of the Rebellion. The Empire is made up of a sea of white male faces (mostly with British accents), the kind of people who, generations before the 1970s, made their own empires on Earth. The Rebellion is a panoply of human and alien races, whose greatest, most heroic leaders and authority figures are women (Princess Leia and Mon Mothma). While we wouldn’t get an actual non-white human until The Empire Strikes Back, the diversity of the Rebellion in the face of the monolith that is the Empire was still evident. The inclusion of Billy Dee Williams’ Lando Calrissian as a person of color instantly becoming the sexiest, most confident person in the galaxy, a governor of a very prosperous colony, is a bold statement in itself. This is not a galaxy for just the faces of the Empire, this is a galaxy for everyone.

The addition of Billy Dee Williams to the cast of the franchise in The Empire Strikes Back does highlight the lack of non-white characters in the cast of A New Hope. Trying to put myself in the shoes of a black nerd in the world in 1977 and seeing the largest mass market appeal of science fiction in the 20th Century might have been both thrilling and frustrating. To see A New Hope, but also see the only non-white human face (and voice) be provided by James Earl Jones, playing (what we would find out later) a white character, one of the most evil sentient beings in the galaxy, willing to choke another person to death as soon as look at them, might have been difficult. Sure if I was 14 that might have been awesome because Darth Vader is a badass and one of cinema’s greatest villains, but if I was 9, searching for something to identify with in the space-faring faces I saw on screen, or 35, finally seeing my love of fantasy and science fiction come to the big screen and embraced by America in such a full-throated way, yet still left out of the story, I don’t know how I would have felt.

This is why any cultural phenomenon as large as Star Wars becomes political no matter what its creators intended. Everything from merchandising, to the jobs it creates, to the content on screen reaches literally millions of people, many of them looking for something to identify with. I’m not saying people of color can’t find something to identify with in a film of all white characters, but for something as worldwide as Star Wars, we could stand to see more of the world in it. Lucas however, always intended for his films to be political.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, George Lucas forged a deep and abiding friendship with fellow young pioneer filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola. Through their artistic and personal relationship, the two shared ideas about movies that would eventually become THX-1138 (whose financial failure would strain their friendship) and Apocalypse Now. While Coppola had guerilla filmmaking dreams about a Cinema Verite-style docu-drama in Vietnam (which Lucas would direct), Lucas dissuaded him of such quixotic thoughts. While Coppola’s political ideas about the horrors of Vietnam would eventually see fruition in 1979’s Apocalypse Now, Lucas was consciously inspired by Vietnam when creating Star Wars. Generally the idea of a small, desperate rebellion fighting against a vastly superior occupying superpower was present in making the films from the beginning. In the AMC documentary series Stories of Science Fiction, hosted by James Cameron, this exchange between the two filmmakers makes things fairly clear;

Cameron: “You did something very interesting with Star Wars, if you think about it. The good guys are the rebels, they are using asymmetric warfare against a highly organized empire. I think we call those guys “terrorists” today. Well call them Mujahideen, we call them Al-Qaeda.”

Lucas: “When I did it, they were Viet Cong.”

Cameron: “Exactly. So were you thinking of them at the time?”

Lucas: “Yes. […] We’re fighting the largest empire in the world.”

Lucas would further explore the dynamic of the Vietnam metaphor in Return of the Jedi (and the Little Guy fighting against evil empires in general) with an unlikely subject, the Ewoks. As Lucas himself says in the commentary recorded for the film in 2004, the Ewoks were a direct analog for the Viet Cong, utilizing masterful tactics and knowledge of the terrain, despite being severely outclassed in technology and firepower, in order to defeat a vastly superior invading force. This is all in-keeping with George Lucas’s general anti-authoritarian, anti-dictator stance, one he would continue to address thoughtout his career.

This brings me to the prequels, which are a mixed bag to say the least. The political content is very prominent, however, as The Phantom Menace opens with a crawl delineating the taxation of trade routes and the resulting dispute. The opening scene involves clandestine negotiations between the Trade Federation and Darth Sidius, a secret Sith Lord orchestrating a galactic conflict between the Trade Federation and the Republic. While getting into the minutia of trade route taxation isn’t exactly the most thrilling Star Wars plotline ever, it is still directly political, and it will have resonance later in the Prequel Trilogy.

The presence of the Trade Federation does present a rather uncomfortable element in the prequels, and that is of racial caricature. The Neimoidians, the most prominent alien species of the Trade Federation, are presented as weak-willed, cowardly, duplicitous, and greedy, all while speaking with a cartoonish East Asian accent. The much-derided Jar Jar Binks speaks with a strangely rhythmic Caribbean patois, while ambling about like a Jamaican stereotype. Finally there is Watto, whose greed, manner of speaking and prominent nose may have been intended to harken back to Charles Dickens’ character of Fagin, instead comes off as a cruel conglomeration of negative Jewish stereotypes (which Fagin was to begin with).

I honestly don’t believe any of these racial caricatures were intentional. In fact, Ahmed Best, the actor who played Jar Jar Binks on screen and provided his voice, is himself a black man and a talented performer, one who took the negative response to Jar Jar very personally and suffered serious pain and heartbreak because of it. But this all speaks to the importance of representation in a franchise as universal as Star Wars. While it may very well be the case that none of these characters or species were intended to incorporate racial caricatures, taken en masse, in the same film, the connections were unavoidable in the minds of legions of movie-goers, and it was irresponsible for both George Lucas and Lucasfilm to have so little outside creative input that such an amalgamation of stereotypes was allowed to be put on screen. Even though it was not cruel, it was a baffling and ugly set of choices that alienated fans and damaged the brand.

The intentional political messaging of the prequels, however, is a stridently anti-fascist cautionary tale and a commentary on unchecked political power. The Clone Wars (a protracted armed conflict) embolden the Galactic Senate (a political body rendered weak and ineffectual by bureaucracy) to enact emergency war powers, giving unprecedented authority to Chancellor Palpatine (a dictator in waiting), who, unbeknownst to both the Senate and the Jedi, is actually Darth Sidius.

By the third film, Revenge of the Sith, Darth Sidius’s political machinations were coming to fruition, and he was able to manipulate both the Jedi and the Senate into setting his own Reichstag Fire in the Galactic Republic. Just as the Nazis were able to turn the burning of the Reichstag (a fire they caused) into giving Hitler total control over Germany, the attempt of the Jedi to arrest Sidius is mutated into an assassination attempt via propaganda by Palpatine. Sidius/Palpatine’s declarations of the Jedi as traitors and conspirators, his speechifying of “if you’re not with us, you’re against us,” directly correlate Hitler’s own rise to power and blaming of the Jews as “traitors” for Germany’s loss in WWI, as well as the series of economic disasters in that country during the 1920s and 1930s. It is no coincidence that the legions of “stormtroopers” were created as tools to enact the will of both the Nazi hierarchy and the “new Galactic Empire.”

If there’s one lasting legacy of the prequels, it’s the power of Padme Amidala saying, “So this is how liberty dies… with thunderous applause” as she witnesses Palpatine’s plans come to fruition, greeted with cheers by the Senate. It’s Star Wars and George Lucas in a nutshell; beware of dictators, especially those that claim to be acting in your best interests.

Much was made at the time of how Palpatine’s rhetoric mirrored that of George W. Bush in the run-up to the Iraq War and the post 9/11 legislation aimed to “increase security” such as the Patriot Act. While Lucas was probably himself against these actions personally, the reality of production timelines makes these direct correlations mostly post-hoc (The Phantom Menace was released in 1999 after all). However, the fact that the prequels are intended as an anti-fascist fable and cautionary tale about the rise of dictators and was so easily connected to the then-president and his administration, speaks to just how cogent the prequels’ political messaging is (if nothing else), and how important politics are to Star Wars in general.

This brings us to the sequel trilogy which began in December 2015 with The Force Awakens. While the prequels suffer in a myriad of ways for lack of creative collaboration or secondary input, the sequel trilogy seems to suffer from the opposite. That is, opposing viewpoints from multiple sources working at cross-purposes. While episodes VII-IX have all been stylistically gorgeous, contain astonishing special effects, some great performances from a fantastic company of actors, they have also been narratively incoherent and thematically incomprehensible. Therefore, I believe the sequel trilogy to actually be the least political set of films in the Star Wars cannon (excepting Solo, which is perhaps the most pure Fun Space Adventure of the theatrically released Star Wars content).

There is definite political messaging in The Last Jedi, with director Rian Johnson’s themes of “let the past die” and that perhaps we don’t have to be the 1,001st scion in a line of Famous Space Wizards to be important in the galaxy. Johnson’s criticism of the Skywalker line, of the failure of the Jedi in general, is in-line with his class politics (“Eat the Rich”), presented in a much more cogent and entertaining way in his 2019 film Knives Out. J.J. Abrams, director of The Force Awakens and The Rise of Skywalker however, is obsessed with the past and wants to preserve it for future generations. He believes in long legacies and carrying on the beliefs and foundations of legends that came before. While we can certainly have great, crowd-pleasing science fiction films with either of these themes in mind, it seems counterproductive to do both at the same time, or at least successfully.

But do Johnson or Abrams have the “right” to interweave their politics or beliefs into Star Wars? I would argue, emphatically, yes. I wish we could have gotten better films, but even A New Hope was preoccupied with legacy and carrying on the work of past generations. In his creation of his story, Lucas’s own incorporation of tropes from Westerns and science fiction serials, not to mention plot and filmmaking techniques of Akira Kurosawa, as well as constructing his entire mythos after the theories of Joseph Campbell, made his own story as an artist one inextricably interwoven with the idea of legacy. On screen, Luke is presented with an ancient, dying religion practiced by a near-extinct band of warrior monks known as Jedi, and he subsequently makes it his mission to resurrect that tradition, like his father before him. In the prequels however, Anakin Skywalker is a literal slave who rises up to become one of the most powerful beings in the galaxy, slaying all sorts of counts and generals and defying “masters” along the way. The class politics of those actions are hard to ignore in themselves.

The character of Rose Tico, played by Kelly Marie Tran, should have been the most cogent and important political message in The Last Jedi, and perhaps all the sequels. She represents a blue collar hero, someone who, through hard work, talent, and inherent goodness, could rise to be just as important as generals and “chosen ones.” So, of course, the film sends her off on a side quest that accomplishes nothing besides separating Finn (John Boyega) from Poe (Oscar Isaac), the two characters with the greatest on-screen chemistry, from each other for an entire film. Then, of course, Abrams throws Rose away in The Rise of Skywalker, along with everything else Johnson was doing, and has her do little except ask other characters what she should do next. It’s an unfortunate fate for a character and actress who faced such venomous, and even racially motivated attacks from social media trolls. John Boyega experienced this as well when it as revealed that he was *gasp* a black stormtrooper, but that quickly died down once The Force Awakens was released.

It feels as if Kelly Marie Tran became a cypher for everything negative fan culture didn’t like about The Last Jedi, and the fact that such vitriol mutated into racist attacks is a sign of why representation is important in cultural behemoths like Star Wars. The mere fact that racist tactics were used to attack Tran and Rose is a sign that, in certain areas of fandom, white is the “standard,” and every non-white person is subject to marginalization and attack because of their perceived “otherness.” Speaking as someone who did not like The Last Jedi for what it put on screen as a story, witnessing the reaction some “fans” had was positively vile.

So I don’t know what Disney’s endgame was (or is). From the on-screen content of these films, it’s clear that they don’t have one from a creative standpoint, and I don’t think it’s any sort of feminist or social justice-motivated agenda. Disney is a corporate machine whose goal is to sell us movie tickets, porg dolls, and week-long vacations to exorbitantly expensive theme parks. Its abandonment of Rose in The Rise of Skywalker is proof enough of that. Feminism is not on its To-Do list.

I don’t think there is a feminist agenda on screen either, since I find Rey to be an endearing, compelling character, certainly not a Mary-Sue. She is so insecure about her place in the Universe, about her background and how that plays into her relationship to the Force, that she nearly turns to the Dark Side every time that chump Kylo Ren makes psychic goo-goo eyes at her from across the galaxy. She is often desperate and alone, even when in the presence of her friends. She is constantly searching for mentors or ways to attach herself to a legacy (a holdover from her time spent as an orphan, barely scraping by as a scavenger on Jakku). These are deep psychological scars, ones that run as deep as any physical disability. They inhibit her from making lasting relationships, even with people whom she has a connection with. She has friends sure, but she keeps these individuals at a distance (except Leia, who finally acquiesces to being Rey’s “master” of sorts in The Rise of Skywalker, and Chewie, who has a habit of adopting capable yet mentally scarred wayward young adults). It’s only after she is able to bring Kylo Ren back from the Dark Side that she is willing to accept her own strength, and that she is loved, to truly face the darkness within herself, and thus in turn, the Emperor.

None of this seems particularly agenda-driven to me, at least in any sort of political way. The Force Awakens was a Disney corporate board room’s version of what they thought the world wanted from a Star Wars movie, The Last Jedi was a meta “f-you” to everything Star Wars has done (especially the nostalgia exercise that was The Force Awakens), and The Rise of Skywalker was a “f-you” to The Last Jedi. Rian Johnson’s class politics are in The Last Jedi, sure, but he doesn’t do anything interesting or substantial with them like he does in Knives Out, and certainly nothing as cohesive as Lucas’ anti-fascist messaging in Episodes I-VI. Sure, Episodes VII-IX have something to say about legacy, forgiveness, what we owe to the past, what the past owes to us, and what we owe to the future, but as they are so varied and often oppositional, the social or political messaging comes off as tasteless gruel. It’s there, but it offers nothing of substance and is easily forgotten.

What the sequels do give us are some wonderful characters played by some grade-A movie stars. I wish we had better movies for these characters and these actors, but whatever they represent, they carry within themselves. The friendship of Finn and Poe, the charisma of Oscar Issac and John Boyega, and the inner strength of Daisy Ridley as Rey speak more poignantly than anything Disney tried to give us.

Are there futures to these characters or these stories? I don’t know. I would certainly love to see an exciting, independently-minded filmmaker’s take on, for example, a Finn and Poe buddy picture. A standalone Rey movie where her story arc is taken out of the hands of directors trying to use her as a proxy for dumping on another director’s work? Sounds great! But for now, I’m content to love Rogue One, The Mandalorian, and even Solo for the underappreciated, unlikely triumph that it is. And hey, we have more Ewan McGregor as Obi-Wan Kenobi and maybe even a Taika Waititi-directed film to look forward to so there’s always hope.

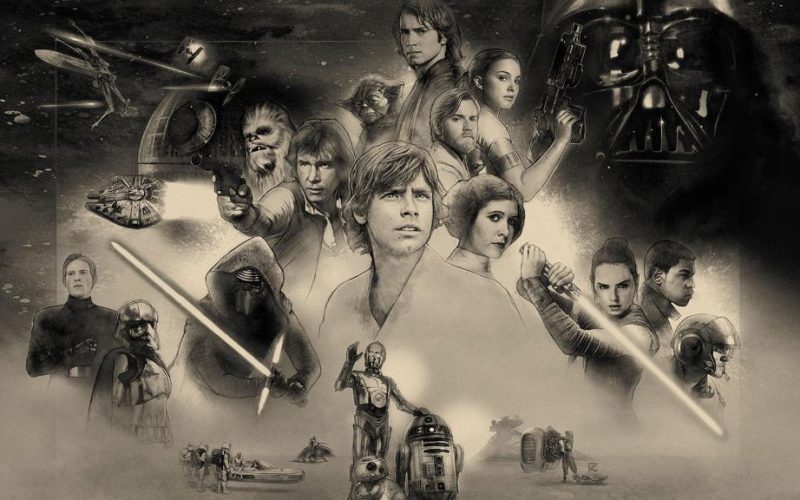

Artwork by Paul Shipper Studios.