Going Global – The Second Golden Age of Kung Fu Movies – 1980s & 1990s.

I argued in the last essay that the 1970s were a golden era for Martial Arts films. Made in the then British colony of Hong Kong, they were a means of expression, a connection with the colony’s Chinese past. Hong Kong had for a long time been heavily influenced by foreigners, and martial arts films often told stories of easier times.

China in the 1970s was still in the grip of Chairman Mao, and even after his death in 1976, the country still restricted the release of foreign arts. Hong Kong however, was developing into an Asian powerhouse and its film industry was rewriting the action genre rule book.

The 1980s continued this. The genre was growing up, developing and adapting to new influences and technologies. Giants such as the Shaw Brothers Studio lost influence whilst trying to expand around the world (for example, investing in Ridley Scott’s 1982 sci-fi masterpiece Blade Runner), whilst artists who were experiencing their first big break at the close of the decade, stood on the verge of world domination.

Building on the foundation laid by the legendary Bruce Lee in the 1970s, this decade witnessed a surge of creativity, innovation, and international recognition for martial arts movies. Artists such as Jackie Chan, Sammo Hung, Tsui Hark, and choreographer turned director, Yuen Woo-ping emerged, changing the direction of Hong Kong action cinema into an even more dynamic version of its old self. The early 1980s saw the emergence of visionary directors who played a crucial role in elevating Hong Kong martial arts cinema to new heights.

The most prominent of these was probably Jackie Chan. From the late ‘70s into the ‘80s, ‘90s and the new millennia, he produced, directed and starred in hit after hit. In 1981 he attempted to break into Hollywood via the Golden Harvest coproduction, The Cannonball Run, with limited success although that too seemed inevitable. He finally succeeded in the 1990s.

Unlike traditional martial arts films that focused more on action and drama, Chan introduced a comedic element to the genre. Humour had often played a part in Martial Arts films. Think of Bruce Lee’s hungry belly noises (an obvious tip of the hat to Charlie Chaplin’s masterwork, Modern Times), and inability to order in a restaurant in The Way of the Dragon (1972).

Chan, however, made comedy a part of the martial arts process. His films seamlessly blended martial arts choreography with slapstick humour, creating a unique and entertaining experience for audiences. The humour in Chan’s films often stemmed from his character’s resourcefulness, ability to turn everyday objects into weapons, and physical comedy. This innovative approach to combining martial arts and comedy had a profound impact on subsequent generations of filmmakers. Directors like Stephen Chow and Edgar Wright, known for their comedic and action-packed films, have cited Chan as a major influence. The success of Chan’s Kung Fu comedy formula not only entertained audiences but also paved the way for a new subgenre within martial arts cinema.

This can be demonstrated in such films as Project A (1983), directed by and starring Chan. Another Golden Harvest production, Project A was marketed as Jackie Chan’s Project A, a clear indication of his ascent in the industry. Its elaborate action sequences, including a breathtaking bicycle chase, demonstrated Chan’s commitment to pushing the boundaries of the genre and of Kung Fu.

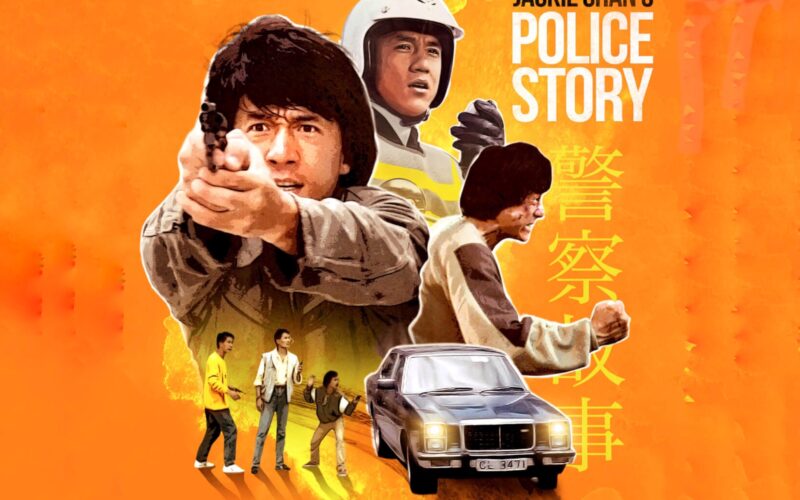

His masterpiece, however, is undoubtedly 1985’s Police Story. Again directed by and starring Chan, Police Story stands as a magnum opus in the realm of action cinema. This iconic film not only showcases Chan’s unparalleled skills as a martial artist and stuntman, but also marks a defining moment in the evolution of the action genre. The stunts are gobsmacking and Jackie Chan’s Stuntmen Association (as his group of stuntmen were called) sometimes go to the limits of what can be achieved by the human body without causing lasting damage. People are thrown down escalators, catapulted off moving vehicles, and smashed in a department store’s worth of furniture, much of it made of glass. Nothing seemed off limits. The highlight, however, is the finale.

Police Story centres around Chan Ka-Kui (Jackie Chan), a dedicated police officer assigned to protect a key witness in a drug case. In the climax, the witness has managed to get her hands on evidence that could incriminate the drug lord. The whole scene, which takes place in a multi-level shopping mall, lasts over ten minutes culminating in a jaw dropping stunt. Chan is at the very top level of the mall. The briefcase with the evidence is at the bottom. The bad guys are close and will be able to get to it easily. About 10 feet away is a pole that descends to the ground floor. The pole is wrapped with lights and wires. Chan has to leap through the air, grab onto the pole and slide down. As he does so the lights explode around him. At the bottom he painfully crashes into a display, smashing the surrounds as he does so. Because of all the lighting on the pole, it had become very hot. Chan didn’t realise this until he had grabbed around it and luckily he was able to control the natural instinct to let go. He ended up with second degree burns on his hands.

The stunt was so impressive that, in the film’s finale, it’s shown repeatedly from different angles over and over again. What’s even more impressive was that Chan was filming Police Story in the day, and another film, Heart of Dragon, directed by Sammo Hung, at night.

Alongside Chan and the stunt team, the stars of Police Story, are the cinematography by Cheung Yiu-Tsou, and the editing by Peter Cheung which enhances the pacing of the action, allowing the audience to fully appreciate the intricacies of Chan’s choreography.

Police Story won several awards, including the Hong Kong Film Award for Best Film and Best Action Choreography. Its success marked a crucial step in breaking down language and cultural barriers, introducing Chan’s unique style to audiences around the world.

By the time he made Police Story, Chan had started to make more international films whilst sticking to his tried and tested formula of comedy and action. Meals On Wheels (1984), another film directed by Sammo Hung, climaxed in a Spanish Castle, in Armour Of God (1986) he travelled to the former Yugoslavia, and to New York in Rumble In The Bronx (1995) although it was actually filmed in Vancouver. He even leant his voice as the Beast in the Chinese dub of the Disney’s Beauty & The Beast (1991). By the mid 1990s he was finally cracking Hollywood with films such as the Rush Hour series (the first released in 1998, the second in 2001 and the final film in 2006) Shanghai Noon (2000) and its sequel, and the remake of The Karate Kid, (2010), in which Chan, despite the name of the film, teaches Will Smith’s son Jaden Kung Fu.

Up until 1982, the majority of Martial Arts films were made in Hong Kong. The first collaboration between Hong Kong and China was The Shaolin Temple, and it was filmed entirely on the mainland. It also happened to be the first film to feature Jet Li (credited at the time as Jet Lee). Born Li Lianjie, Jet Li trained with the renowned Wushu teacher, Wu Bin and by 1979 he had become the Men’s All-Around National Wushu Champion five times. Directed by Chang Hsin Yen, The Shaolin Temple was a massive hit, propelling Li to almost immediate success. The follow-up, Kids of Shaolin was equally successful.

Li went on to star in a number of successful and important martial arts movies including the Once Upon A Time In China series, Fist of Legend (1994), Fearless (2006), and Hero (2002).

The Once Upon A Time In China film series, produced and sometimes directed by Tsui Hark for Golden Harvest, showcases many of the tensions that were taking part in China at the time. Set in the final years of the Qing Dynasty and the 19th Century, Li plays the legendary hero Wong Fey Hong. It was a time of increasing Western influences and the introduction of new technologies, including firearms. Some are embracing this influence, including the love interest known throughout the film, 13th Aunt (played by Rosamund Kwan Chi-Lam). Others see it as an opportunity for power, wealth and influence. Wong Fey Hong and his followers are most reluctant to embrace the foreign influence, and it’s this tension that propels the film. This is highlighted by the threat of guns and cannons, technologies that threatened the Martial Arts and, by implication, threatened Chinese heritage. This tension is a metaphor for what was happening (and continues) in China itself. The ruling Communist government were slowly opening up to Western countries and were happy to reap the potential rewards, whilst also being reluctant to relinquish control. Only two years before the release of Once Upon A Time In China was the Tiananmen Square massacre, an event that was seen throughout the world, yet hardly ever seen in China itself.

With Fist of Legend, Jet Li was stepping into some very big shoes as it’s a remake of Bruce Lee’s 1972 film Fist of Fury. Directed by Gordon Chan, Fist of Legend was something of a disappointment at the box office even though it’s often cited as one of Li’s best films. It was, however, embraced around the world and on its UK television debut was watched by over a million viewers. Much of this success can be attributed to the star as the film was distributed outside of China as Jet Li’s Fist of Legend.

Like many of his contemporaries, Jet Li tried to break into Hollywood, although to only middling results. His first film was Lethal Weapon 4, which also marked the first time he played a villain. It’s a fun film but a pale reflection on the earlier instalments. Li however, is cool and dangerous throughout. His most successful films there are probably the Expendables series, and he most recently appeared in the Disney’s live action Mulan (2020) where he played the Emperor of China.

Perhaps the actor with the most staying power has been Michelle Yeoh, which is ironic given she almost quit acting after getting married in 1987. It wasn’t until after her divorce in 1992 that she restarted her career. The 1980s saw a notable shift in the portrayal of female characters in martial arts movies. Actors like Yeoh and Cynthia Rothrock broke new ground proving they were as good as the men. They both starred in Yes, Madam (1985), directed by Corey Yuen, which perfectly illustrates this new equality.

Born in Malaysia, Michelle Yeoh Choo Kheng, started her career as a model and represented Malaysia at the Miss World 1983 pageant in London. She came in at 18th place. Her first acting job was in a commercial for Guy Laroche watches, and she appeared alongside Jackie Chan. She was on an upward trajectory in her career when she married her first husband, Dickson Poon, a co-founder of D&B Films, and decided to step away from acting, a hiatus that lasted five years. Her first film back was a classic – the third of Jackie Chan’s Police Story films, Police Story 3: Supercop. In this we must wait some time to witness Yeoh’s skill at Martial Arts but when we do, it’s thrilling.

In the ‘90s Yeoh also starred in the Yuen Woo-ping films Tai Chi Master (1993) starring Jet Li and Wing Chun (1994) where she co-starred with Donnie Yen.

It could be said that Donnie Yen was born into the martial arts. His mother, Bow-sim Mark, is a Fu-style wudangquan (internal martial arts) and tai chi grandmaster, and Donnie’s interest was kindled when he was just a child. He started his career as a stuntman in the 1980s before starring in the Yuen Woo-ping directed Drunken Tai Chi. It was an opportunity for him to show off not only his martial arts skills, but also his breakdancing abilities. Yen and Yuen would work together numerous times in the following decades producing some of the most notable films of the genre.

One of these is the brilliant 1988 actioner, Tiger Cage, but his breakthrough was starring opposite Jet Li in the second of the Once Upton A Time in China films. In this, Wong Fei-hung (once again played by Jet Li) rescues a group of children who were attacked in their international school by the nationalist White Lotus Sect – a group trying to rid China of all foreign influence. Not only is he up against the sect, but also the military, headed by Yen’s Nap-lan Yun-seut. The two stars spar early in the film, but it’s all set up for the big fight at the end, and it’s a fantastic encounter. Director Tsui Hark keeps it moving at breakneck speed, allowing the two performers to showcase their talents and give us a majestic display. Once Upon A Time In China improves on the already great first film. Its politics are clearer, and the narrative is less muddy.

In 1993, Yen once again worked with Yuen Woo-ping in my favourite martial arts film – Iron Monkey, produced by Tsui Hark. Yen plays Wong Kei-ying, a physician and martial artist from Foshan, and father of the aforementioned Wong Fei-hung. One day father and son arrive in a small town whose local physician Yang Tianchun (Yu Rongguang) is living a double life. In the day he is a well-respected doctor who gives free treatment to the poor (subsidised by charging richer people a premium). At night, Yang dons a black mask and becomes Iron Monkey, a Robin Hood type character who steals from the rich and gives to the poor. The authorities are frantically trying to capture Iron Monkey and, after witnessing Wong Kei-ying’s skills, he becomes a suspect. His son, Fei-hung, is held hostage by the authorities to allow Wong Kei-ying to prove his innocence by catching the real vigilante. Yang agrees to look after the boy whilst the search continues. Wong and Yang become admirers of each other and friends, not knowing that they are hunter and prey. Once again Yuen delivers the goods, including another thrilling final fight (which takes place on top of wooden poles of various lengths in the middle of a fiery inferno) and a wonderful scene in which a gust of wind blows a pile of paper into the air. This is all rescued in balletic and graceful form by Yang and his assistant and fiancé, Miss Orchid (Jean Wang). It’s a wonderful scene that highlights how the athletic skills of the performers are not just for violence. This is extends the arts into dance, worthy of any spectacular Hollywood musical.

Whilst Yen did enjoy a level of success in the 1980s and 1990s, it wasn’t until the 2000s that he really came to prominence, starring in films such as the Ip Man series, and opposite Jet Li once more in the 2002 Yimou Zhang film, Hero.

Tsui Hark, widely regarded as one of the pioneers of the era and often called the Steven Spielberg of Asia, directed such iconic movies such as Zu Warriors from the Magic Mountain (1983) (which was a major influence on John Carpenter’s Big Trouble In Little China – 1986), and Peking Opera Blues (1986). Tsui had the gift of combining the mythology and heritage of his homeland with the technology and special effects of Hollywood.

In 1991, Tsui directed the first in the aforementioned Once Upon a Time In China films starring Jet Li. These were massive successes and highly influential, with a kinetic directorial style and some of the greatest action sequences in film history. The fight on the ladders towards the end of the first film is thrilling and gravity defying. It, along with its sequels (some of which were also directed by Tsui), concentrated on the (exaggerated) exploits of Wong Fei-hung (1847 – 1925), a physician and founder of a martial arts school in Shui jiao. This is an era defining film as it confronts the fight against Western imperialism and technological change. Here the bad guys are not just Chinese gangs, but also British soldiers and diplomats who have carved out their very own enclave within the country which only the wealthiest Chinese can visit.

Tsui was also a writer and producer, and his credits are hugely impressive: A Better Tomorrow (1986), A Better Tomorrow II (1987), A Chinese Ghost Story (1987), The Killer (1989), The Legend of the Swordsman (1992), The Wicked City (1992), Iron Monkey (1993), Black Mask (1996) and many more.

He also had a short stint in Hollywood and directed the Jean Claude Van Damme actioners Double Team (1997) and Knock Off (1998), but soon returned to his homeland, disappointed by the experience and by the lack of control he had in the movie capital of the world.

Yuen Woo-ping, a real favourite of mine, also started to emerge in the late 1970s. In the West he is perhaps best known as the choreographer on The Matrix (1999), Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000) and the two Kill Bill films (2003 & 2004), but he was also a director of renown. His directorial debut was the Jackie Chan starring Drunken Master (1978) and he also directed such films as Dreadnaught (1981), In the Line of Duty (1986), and two of my favourite action films, Tiger Cage (1988) and Iron Monkey (1993).

Tiger Cage, a film that mixes John Woo action and martial arts, is a stripped down, kinetic film featuring a young Donnie Yen (originally credited as Michael Ryan). Coming in at only 93 minutes, it stacks action sequences one on top of each other, and moves at a frenetic pace whilst also taking a few surprising turns. The first ten minutes features one long shootout, that starts indoors and then spills out into the surrounding streets. Fast, bloody and violent, not all of it makes sense, but it’s wonderfully thrilling. It also features a fight between Yen and Stephan Berwick, the American martial artist and scholar of the genre, which was used in the US trailer.

Another Choreographer who made a real impact during this period was Corey Yuen, who brought his skills to such films as The Prodigal Son (1981), Yes, Madam! (1985), Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain (1983) & The Mighty Peking Man (1977). He was also a director, probably best known in the US and Europe for the 2002 Jason Statham film, The Transporter.

Many actors in this period came to fame and, for many around the world, became the faces of the genre. People like Jackie Chan, Jet Li, Michelle Yeoh and Donnie Yen all crossed over from Hong Kong to Hollywood to greater or lesser degrees and one, Michelle Yeoh, actually won an Oscar in 2023.

The 1980s marked a golden era for Hong Kong cinema and at the forefront of this cinematic revolution stood Golden Harvest, a film production company that played a pivotal role in shaping the landscape of martial arts and action films. Renowned for its commitment to innovation, star power, and global appeal, Golden Harvest produced a plethora of iconic films during this decade that not only defined the era but also left an indelible mark on the history of cinema. Many of the films I have discussed here were produced or co-produced by this studio. What set them apart from the rest was their willingness to innovate. While traditional kung fu films continued to find success, the studio embraced new and exciting sub-genres such as kung fu comedy, heroic bloodshed, and fantasy martial arts.

One of the innovations that Gloden Harvest produced was the introduction of wire work in stunts. It had long been a tradition of characters leaping great distances in the middle of a fight. In Joseph Kua’s 1974 film Shaolin Kung Fu, the protagonists leap over a huge lake in pursuit of each other. A character jumps, there is a close up of them flying through the air, and suddenly they are sixty feet away. Wire work allowed the directors to show the entire leaps in camera. Wire work (also known as wire-fu) had been used in Japan in the mid 1970s (see Sister Street Fighter (1974), for example), but it was Zu: Warriors from the Magic Mountain that really popularised the process. It’s an effect that helps stretch the form of Kung Fu into something more. The Once Upon a Time… films use it to a great extent, as does Iron Monkey. The paper scene is a perfect example of this. However, it wasn’t until the late ‘90s and early 2000s that wire-work became known internationally. Examples of this are The Matrix (1999, directed by the Wachowski’s, with choreography by Yuen Woo-ping), Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000, directed by Ang Lee with choreography again by Yuen Woo-ping) and House of Flying Daggers (2004, directed by Zhang Yimou).

The 1980s and ‘90s were a special time for martial arts films and Hong Kong action films in general. I have tried to concentrate on Kung Fu films, but the colony’s influence was much wider. This was also the time of Ringo Lam (City On Fire – 1987), Peter Chan (Comrades, A Love Story – 1996), Wong Kar-wai (Chungking Express – 1994 & Fallen Angels – 1995) and the Mozart of Mayhem himself, John Woo (The Killer – 1989 & Hard Boiled – 1992) – filmmakers who themselves were having an impact on the wider world of film.

It was an exciting time and an area of filmmaking which was constantly redefining itself, and recreating action cinema around the globe. Some of my favourite films were made in these two decades – Tiger Cage, Iron Monkey, Once Upon a Time in China, and Police Story to name a few – all hold a special place in my heart. They are the films I judge all other action films against.

They also represent a growing confidence in China by the Chinese government and people. If the ‘70s were a time of rediscovery and rebirth, the ‘80s and ‘90s were a time of teenage rebellion – rebellion against the norms of the genre and, more widely, against international perceptions. Influences from around the world were adopted and moulded into something unique, then sent out into the world to influence us all back.

Filmmakers were still regularly looking into the past, adapting stories, legends and myths and telling them in a new form, but they were also looking forward. The future of Chinese cinema, and how it served as a reflection on the country itself, was starting to reveal itself. The handover of the control of Hong Kong was still 5 years away, however the nationalistic tendencies of Once Upon A Time in China were a portent of the increase in state involvement that was to come. Times were going to change, but in the meantime, there was a hell of a lot of fun to be had.