Hugo (2011).

Even for a director as diverse as Martin Scorsese, his 2011 film Hugo is a bit of an anomaly. Whilst the perception that he is obsessed with gangsters is undoubtedly incorrect and his filmography is actually much wider than people often assume, Hugo still stands alone. Even The Age Of Innocence, which centred around wealthy New Yorkers in the 1870s, explored themes that he had touched upon in the past – the role of an individual in a strict conformist culture or society for example, which was also examined in films such as Taxi Driver and Goodfellas.

Although he had made costume dramas before (the aforementioned The Age of Innocence and Gangs of New York for example) Scorsese had never previously made a children’s film. Also surprisingly, even though he had made a TV series about cinema, this was only his second film to touch upon the history of film, the first being The Aviator only a few years before.

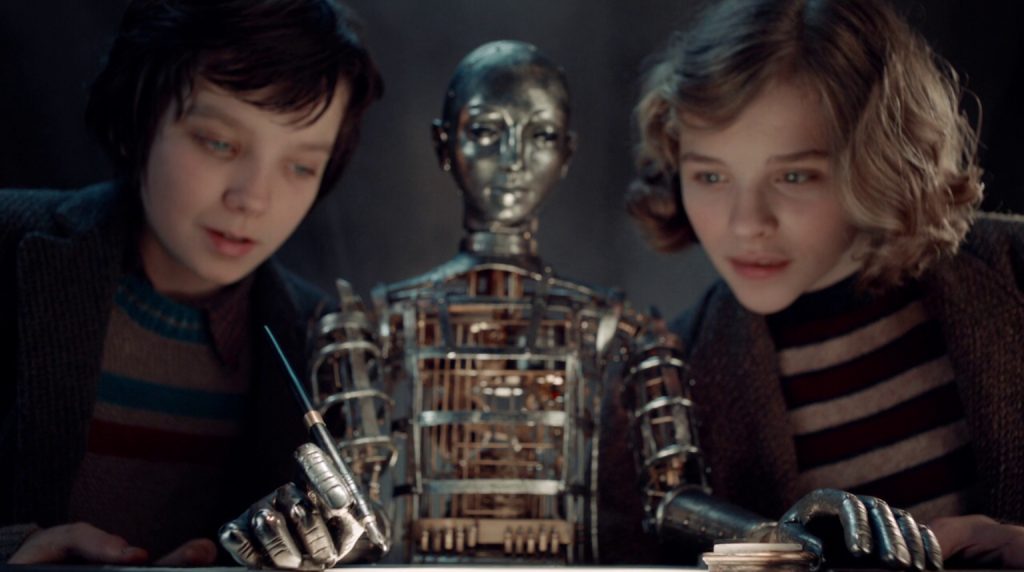

Based on the book The Invention of Hugo Cabret, Hugo tells the story of a young boy whose clockmaker father has died and who now lives in the clock tower of Gare Montparnasse Railway Station. He lives alone as his uncle – the man who is supposed to be maintaining the station clocks – has gone missing. Hugo spends his days wandering the train station and continually trying to avoid the clutches of the station master, Gustave Dasté (Sacha Baron Cohen), a cruel and vindictive man determined to catch every orphan who comes through the station and send them off to the orphanage. Hugo is alone and the only thing that keeps him company is an automaton that his father had once found and, with Hugo, had attempted to repair.

Then one day Hugo meets Isabelle (Chloë Grace Moretz) after being caught stealing from her godfather’s toy kiosk in the station. This seemingly mean old man, Georges, confiscates Hugo’s notebook which had once been his father’s. It is this notebook, coupled with Isabel’s upbeat encouragement, that guides Hugo into the past where he will discover the true identity of this gruff old toy seller. Georges is of course the legendary pioneer of silent movies and the man many credit with inventing special effects, Georges Méliès.

Hugo is not strictly accurate with regard to what happened to Méliès’ after his film career ended. For example, the character of Hugo Cabret is completely fictional as is the investigation that lead to his rediscovery. However, the significant points of Méliès’ life – the fact that his career came to an end with the onset of the first world war, that his films were melted down and used to make heels in women’s stilettos, and the fact that he worked in a toy kiosk at a train station – are real.

The attraction here are the details about Méliès’ life and glimpses into this pioneering era of film history. These include some wonderful moments where we get a peek behind the scenes at the Méliès studio on his property in Montreuil, just outside Paris. This is a moment in film history that is often forgotten by mainstream audiences, and Hugo gives us a wonderful glimpse into the frenetic creativity that went into making these wonderful films. According to Méliès’ memoirs, his use of stopping the camera to make things on screen disappear or to change into something new began when one of his cameras jammed. Playing the picture back he noticed that people who one moment were in the frame were suddenly gone, whist others mysteriously teleported from one position to another. Méliès’ genius was that he recognised the potential of such a happy accident. He was a born showman, a magician and a storyteller who knew exactly how to use this new technology.

Scorsese shows us what it was like to work in this environment and we are able to peer into the inner workings of the studio. We see the elaborately decorative stage, the giant rope-operated dragon that stalks the screen breathing fire, and the moment when Méliès cries out “Freeze!” with vibrant, almost manic energy, he jumps forward onto the stage and organises the transition – a cut from the actors dressed as skeletons to the fireworks that will, when the filming resumes, make it look like the performers have exploded. This magical frenzy is the closest we will ever get to experiencing that ground-breaking time. A time when the language, in its simplest and most foundational sense, was being invented. This is the moment that special effects were born.

Ben Kinglsey plays Méliès as a man who has been beaten by life, who has faced so much adversity that it is easier to now give up dreaming and pretend that the past, in its glory as well as its misery, no longer existed. And this is the core of the film, its moral centre.

Hugo is at that point in life when he may soon have to make the same decision that Méliès once had. Does he hold on to the dream, or does he give up? At the start of the film he still holds on to some faint hope that there is more to life and this provides the emotional propellant that drives the narrative. The automaton – a robot like figure that was designed to look human and to perform basic functions, like the animatronic figures we see in theme parks and arcades around the world – is the catalyst, the embodiment of all that he dreams of. Together with his father he rebuilt it but they never discovered its function and Hugo, in the manner of the child that he still is, believes that this mechanical man holds some deep profound message that will help him in his grief and loneliness.

Even the Station Manager is looking for something and is on the verge of giving up. What Dasté so desperately needs is love. He sees Lisette, the florist (played by Emily Mortimer) everyday but can’t bring himself to ask her out. He’s handicapped not just because his leg, which he injured during the war, but by his profound shyness. Each character has to overcome something, to let the past go in order to get on with the future.

Hugo is a love letter to silent movies and the man who was so influential in making them. Just as The Aviator is about the pioneering spirit that drove Hollywood, Hugo is about that same inspiration and how fragile it all is. In many respects it‘s an allegory of the general plight of silent movies. The American Library of Congress estimates that 75% of all silent films are now lost, while the German archive Deutsche Kinemathek – Museum für Film und Fernsehen estimates this could be as high as 90%. The main reason for this is simply because the studios thought they were worthless. They were destroyed and the nitrate film reused. Some were left to rot in dungeon-like basements and others were lost to tragic accidents. It’s said that the full 9 hour cut of Eric Von Stroheim’s 1924 film Greed was found in the MGM vaults in the 1950s only for it to be destroyed by executives who didn’t realise the treasure they possessed. Whether this story is true or not it certainly illustrates the tragedy of so many lost classics and the very real possibility of more losses in the future in this digital age where movies are increasingly being held on digital media formats as opposed to physical film.

Just as Méliès is rediscovered and celebrated at the end of Hugo, there are still stories of silent classics being discovered every few years – a missing three reels from Metropolis were found in Argentina in 2008 and the BFI recently released a 5 hour version of the Abel Gance epic Napoleon but such instances are few and far between. Yet this hope that classic films can be restored still remains. Scorsese himself helped establish The Film Foundation which has so far restored 850 films.

But you don’t need to be a cinephile with a thirst for silent movies to enjoy Hugo. It has so much to offer from fantastic performances, beautiful cinematography by Robert Richardson and great special effects. The film was originally released in 3D and made great use of the technology having been filmed in native 3D, which allowed Scorsese to specifically create shots with the image in mind.

Hugo is a simple story – a children’s tale certainly – but with a message close to a cinephile’s heart. It has some wonderful characters, some moments of action and peril and a story of redemption and rediscovery that makes the viewer feel warm inside. It’s proof that Scorsese can approach any subject and make a film that is interesting, entertaining and personal. I’ve watched it alone and with my children who have enjoyed it numerous times and hopefully it will act as an introduction to the importance, entertainment and wonder of silent film for those unaware of its magic.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 9/10