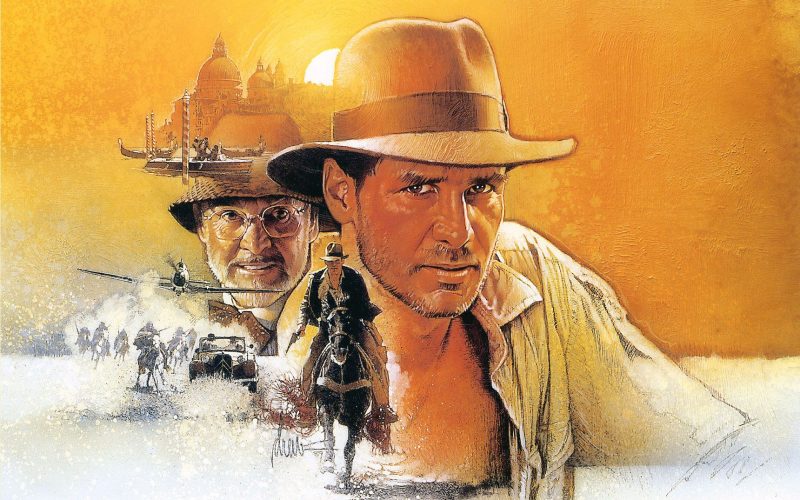

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989).

For me, Raiders of the Lost Ark is peak cinema. It is unequivocally one of the greatest movies ever made, one that embraced all the miraculous possibilities of film promised to children who watched everything from adventure serials to James Bond in their youth, yet synthesized with the creative brilliance and scale of Steven Spielberg and George Lucas. As with many of my generation, the kids who grew up with access to VHS and video stores, there was never a time that I can remember having not seen the Indiana Jones movies. They were just always around, much to my great fortune (and glory). These films, even as a kid who could barely grasp the subtleties and nuances of the English language, I realized were things that actual humans like me made. The guy who played Han Solo is wearing that fedora and being a hero again, the guy who directed Star Wars has his name on these movies, and the guy who directed E.T. directed all the Indiana Jones films. These wonderful, brilliant men were all contributing to this body of work that brought so much joy to my childhood, and it was Indiana Jones that helped codify that notion in my barely-formed brain. So, admittedly, my love for these films makes my analysis somewhat biased, but I am approaching them all with unabashed affection because I want to share those positive feelings with fellow lovers of film.

The entire original trilogy has its advocates, each film being the favorite of many people whom I know personally or whose work I admire. Sometimes that favoritism is tied to which entry in the franchise they first saw in theaters or on video, and this could very well be generational. Those old enough to have seen Raiders of the Lost Ark in theaters might hold that as the supreme entry in the series, while if they were a few years younger, they might enjoy The Temple of Doom the most. I have no such “first time” experience because, much like Star Wars, I cannot recall which film I saw first. I have always just known I’ve seen them. So why do I feel The Last Crusade is the best Indiana Jones film (or at least my favorite), even if I concede that Raiders of the Lost Ark is one of the pinnacle achievements in film history?

Upon release, Temple of Doom was decidedly less well-received than Raiders. Sure, the second entry in the series is an exceptionally fun, delightfully bizarre, and well-executed adventure film with excellent performances from its leads and supporting cast. But it has some uneven elements, makes unexpectedly dark turns that took some audiences by surprise, and, most unfortunately, relies on lazy racial stereotypes for broad comedy that mostly falls flat. Do I still love it? Yes, but not as intensely as the first and third films.

So what draws me to The Last Crusade? Sure, there is a sort of self-conscious return to the familiar formulae of Raiders; bringing back Denholm Elliott’s Marcus Brody and John Rhys-Davies’s Sallah, Judeo-Christian MacGuffins, and everyone’s favorite villainous punching bags – NAZIS! Back was also a lighter tone and a greater density of jokes, which might seem discordant when this film has ACTUAL HITLER and Nazis burning books in a rally reminiscent of an apocalyptic cult ceremony. Admittedly that sort of “hey, let’s return to what works” filmmaking has been the bane of franchises and filmmakers in the past, shifting the fragile balance between art, craft, and commerce that is inherent to making movies full-bore into the realm of commerce. Here however, in the hands of a director as skilled as Spielberg, in a lead actor as charismatic as Harrison Ford, and a supporting cast as diverse and accomplished as all the actors assembled, everyone both in front of and behind the camera finds a groove in which they can operate at peak levels of craft and creativity, to dive headlong into the joys of movie-making. The Last Crusade feels like coming home.

The Last Crusade still clings to the serialized pacing and structure of the first two films. Much like the third entry in the Star Wars franchise, Return of the Jedi, released six years earlier, the first section is a totally self-contained mini-movie, one that sets the tone for the subsequent adventure but has little to no bearing on the actual plot. Also, both feature Harrison Ford in peril at the hands of powerful underworld figures. The Last Crusade’s opening salvo of action and adventure however, sets itself apart from the Jabba’s Palace Rescue in Jedi by being a prequel, drafting the blueprints for the character he would become. Sure, it’s a bit ham-fisted to establish the origin of so many iconic Indiana Jones accoutrements in one action sequence (his hat, his whip, his fear of snakes, and Harrison Ford’s facial scar) just to help provide moments of payoff to guide the audience through the opening. The action is so clever, contains such wonderful unearthings of silent movie gags and adventure serial techniques, that Spielberg and Lucas could certainly have gotten away with explaining just one or two Jones traits. Plus, River Phoenix is phenomenal as the Young Indy, providing the necessary balance of arrogance, confidence, foolishness, charisma, and resourcefulness to embody Harrison Ford’s characterization, without having to impersonate Ford. However, the visceral impact of Phoenix rising, horrified, out of a pit of snakes increases the peril for what was, up until then, a more madcap chase through a train of circus props. Most eloquently, the transition from Young Indy being crowned with his signature hat by one sympathetic fellow treasure hunter, into a soaking wet Harrison Ford being punched in the face on a storm-tossed boat is one of the most brilliant transitions I’ve ever seen in a movie. It’s all focused on that damn cool-as-hell hat, a hat that is only cool because Indiana Jones is wearing it. So maybe it’s ok to mythologize our hero just a bit.

Speaking of mythologized figures, the opening also gives us the first glimpse and sound of Indy’s father, Dr. Henry Jones, played by the legendary Sean Connery. As I’ve recently mentioned on the Film 89 Podcast, I’m a sucker for good dad stories, and while Henry certainly is not that, this is the first seed planted in The Last Crusade for a Dad’s Redemption story, one for a father and son to find meaning in each other’s lives, to finally love each other, before the coming global conflagration of World War II might very well end their lives. That is a profound arc for these two stubborn men, and we see how far both Joneses need to go for that reconciliation when Indy comes running to his father with the artifact that was the object of the chase sequence in the first place: the golden Cross of Coronado. Indy is there holding a priceless, sacred relic of gold and jewels that he risked his life for many times over, traveled miles across the American countryside for, battled gangsters and smugglers to acquire, and his father’s response? Make him count in Greek because he needs to calm down. Buoyed by Phoenix’s genuine, teenage eye-roll reaction, it’s an indicative example of a parent profoundly disengaged from his son, and a son desperate but unable to impress his father. Henry Jones is too preoccupied with the contents of his scholarly work; the embodiment of a cliche obsessed academic. We will later find out that he is composing the key to finding the Holy Grail itself: the Grail Diary. It may be important for the discovery of the most famous artifact in history, but it is also a Doomsday Book of Henry Jones’ failures as a father, a catalog of every bit of information in which he gathered, gaining strength and spiritual energy from dusty artifacts and men dead for thousands of years rather than from his own family. He would rather concentrate on his Grail Diary penmanship than even glance at his bloody, sweaty, exhausted child.

“It belongs in a museum!”

Despite the profound, cold distance with which Henry Jones raised his child, that upbringing still gave us a profoundly adventurous, intelligent hero who is willing to put his mind and body on the line, to put aside personal gain, and even to save the world once or twice. He might do so with rolled eyes and an exhausted sigh, but he’s still willing to fight Nazis and evil cultists to do what is right. At the same time, both men are perfect foils for each other; one a doggedly dusty academic who can barely summon the will to look up from his research to eat or drink (or care for his family), the other one so preoccupied with adventure and “field work,” he would rather climb out the window of his university office rather than grade papers.

Indy is finally spurned on to his own grail quest, becoming a 20th Century Grail Knight (the kind his father would have chronicled during his own research) when he is recruited by Walter Donovan, a sort of angel investor for Holy Grail-associated expeditions. Indy is hesitant until he learns Donovan had initially hired the elder Jones and is only coming to Indy now because Henry has disappeared. However out of place Indy feels in this setting of black ties and champagne, of hoarding ancient treasures in private collections rather sharing them with the public, he can’t resist. The ghosts of Indy’s past (his father, his father’s work, the origins of Indiana’s interest in archeology) have come to a nexus in this one upper crust meeting with Donovan. He embarks on a journey to find both his father and his father’s white whale. He would later regret this deviation from his instincts, but if he did, we wouldn’t have this great movie.

During his grail quest, Indy meets Elsa Schneider, played with a balance of ice and exoticism by the great Alison Doody, his father’s former partner in his Donovan-funded expedition. Dr. Schneider is one of the most fascinating characters in the Indiana Jones canon; one in love with her work, in the adventure of finding ancient artifacts, but also in the power that could be gained from them. She is willing to align herself with the Nazis in order to achieve her goals and to manipulate the men around her to get what she wants, never revealing her true motives to any of them. The only person she is loyal to is herself, unconcerned with ideology or the consequences of her actions. Although she would betray the Doctors Jones in favor of Donovan and the Nazis, she has no more loyalty to them than Indiana and Henry. In fact, she would plead for Indy to run away with her with the Grail at the end of the film. I guess a rugged and charming Harrison Ford is a more pleasant partner to spend a lifetime with than Nazis… at least after she had the Grail in hand and all her Nazi partners are dead.

“He was as giddy as a schoolboy.”

In their initial adventures however, Elsa and Indy’s own partnership is solidified in their underground exploration of the Knight’s Tomb while in Italy. Their mutual enthusiasm for finding the next step in their quest is palpable, even as they navigate around rats, subterranean conflagrations, and long-dead bodies. They both are breathless as they explore centuries-old catacombs and make rubbings of a knight’s shield with the thrill of discovery only a true lover of history and the lives of those long-dead can comprehend. In a sad and poignant character moment, when Indy is told of his father’s equivalent enthusiasm, he can scarcely believe it because he never saw his father behave in such a way. In this one exchange, we get an entire history of the Jones Men’s lives; not only did Henry never show Indy any sort of excitement for anything his son did, but if they had only been more open with each other, they could have had a thousand moments like this, of the shared euphoria of discovery. Amid this triumph, there is an echo of a lifetime of missed opportunity, and a brilliant bit of storytelling.

“I should have mailed it to the Marx Brothers!”

After a thrilling boat chase and the revelation that a millennia-old secret society has been keeping tabs on the Grail and Jones (this movie is packed with plot, isn’t it?), Elsa and Indy travel to Castle Brunwald on the Austro-German border where Indy’s father is being held. Although he does rescue his father (in a manner of speaking), Henry and Indy begin castigating and sniping at one another within minutes, especially after Elsa reveals her allegiance with the Nazis and the fact that she had affairs with both Joneses. No matter what heroic deeds of daring-do Indy accomplished just getting to the castle, Henry can do nothing but belittle his son for now needing rescue himself and for bringing the Grail Diary within literal arm’s length of the Nazis. It’s a wonderful emotional mirroring of the end of the Young Indiana Jones sequence, with a father and son who should be embracing and celebrating their reunion, one accomplished only after intense mental and physical struggle, but all they can manage is frustration with an an unwillingness to understand one another.

The pair go on to escape the castle because, hey, it’s an Indiana Jones movie. However, during the escape we are treated to some of the best odd-couple chemistry is cinema history. The back-and-forth energy between Harrison Ford and Sean Connery is so fun and entertaining to witness, entire stories are told in each bout of repartee. Even if the age difference between Connery and Ford was only twelve years, they embody their respective roles so completely as to make every exchange believable. Both actors are bonafide movie stars, among the most famous and charismatic of their respective generations. They know who they are, what their job is in this movie, and how to propel a scene forward. The only reason a film like this works, with its rolling wave of set pieces and sequences, is because Connery and Ford are able to go from death-defying motorcycle chases complete with explosions and physics-defying stunts, to intimate conversation in the time it takes to adjust a fedora. With a sudden shift in filmmaking language and emotional tone, we are privy to the Jones men confronting how Henry was unable to appreciate the love of his wife until he was forced to mourn her death; a long, slow process of family disintegration Indy spent his childhood witnessing. Sure, this is big time adventure filmmaking, but because of the preternatural skill of Spielberg as a director (especially when it comes to troubled father/son stories) and the strength of the two leads, this scene hits just as hard as a punch from Indiana Jones to a Nazi jaw. We care about our leads and believe in their relationship. We see the capacity for love each has for one another and want them to achieve reconciliation just as much as we want them to find the Grail.

“I thought I’d lost you, boy…”

Only a Jones could convince Indiana to go to Berlin. Once the Jones men decide to find the lost Grail Diary, they journey to Berlin to obtain it, which results in a particularly terrifying encounter with both Elsa Schneider and Adolf Hitler himself, both of whom happen to be attending a Nazi book burning. This is a reminder of the very real, very terrifying evil the Jones men are fighting against. The Indiana Jones films are exciting adventures, but there is real horror here, a real world evil, and the fire and madness of this rally reminds us of it.

With the Grail Diary re-acquired, our heroes are off on the trail of the Nazis and the sacred cup itself. The Jones men do take time to sit for a long-overdue conversation (after boarding a zeppelin and punching a Nazi of course) in which they settle into their roles of the son trying his best to impress his condescending father. The characters obviously have a great many things to discuss, years of successive dialogues that parse out the failings of their relationship and where to go from there. Henry however, approaches the subject like an academic review of a scholarly work. “What do you want to talk about?” he says, as if their entire father-son dynamic can be fixed in the time between getting drinks and starting on appetizers. Even with all they have been through together, Henry still cannot empathize with his son, nor can he see the need to repair their relationship. They have yet to connect on a deep, spiritual level. Again, we are anchored to our leads with some subtle and very human performances by Connery and Ford, along with deft screenwriting by Jeffery Boam, Menno Meyjes, and George Lucas. As much flack as Lucas would get for his screenwriting on the Star Wars prequels, when collaborating with Boam, Meyjes, and Spielberg, the dialogue is fresh, natural, and funny. We savor every exchange and are as entertained by conversation as we are glorious action because these characters are fully formed and fun to spend time with.

Speaking of action, we only get brief moments of father-son-not-quite-bonding before the good doctors are interrupted by more Nazis determined to murder them. This time the thrilling action sequence manifests as an elaborate aerial dogfight, in the tradition of the Golden Age of Hollywood the Indiana Jones franchise, in part, pays tribute to. Here (as in every scene, really) special attention should be given to cinematographer Douglas Slocombe, stunt coordinator Vic Armstrong, and the supremely talented visual and makeup effects teams, without which such sequences would not be possible. We are even treated to another wonderful character moment, in which Henry Jones, using nothing but his umbrella and some “tuck tuck” noises, destroys an airplane by scaring a flock of birds into taking off into the plane’s windshield. He struts past Indy, makes up a Charlemagne quote, and walks off as if he already saved the world. It’s a moment that utilizes the perception of Henry, by both Indy and the audience, as an eccentric cloistered academic, in his tweed suit and umbrella, and shows us how he can turn that aspect of himself into a capable, in-the-field operative. It’s a confidence builder for Henry and a moment of both bewilderment and respect for Indy, bonding the two men with the most wholesome of father-son activities, killing Nazis.

In the final approach to the Grail’s hiding place, we are treated to one of the most entertaining chase sequences I have ever had the pleasure to witness. It has horses chasing a tank, furious Nazi-punching, and Marcus Brody and Henry Jones squirting pen ink into a soldier’s face. It’s both thrilling and humorous to watch, but again, the sequence is punctuated by a moment in which Henry thinks his son has plummeted off a cliff to his death. Although Indy can barely stand, he’s wrapped up in an intimate embrace by his father, showing more bare emotion than we’ve seen in the entire film. For a moment, Henry thought all that would be left of his family would be another memory to mourn, like his wife, all before they reached a mutual understanding. Now they both have a second chance, even if Henry immediately reverts to telling his son what to do.

“It’s time to ask yourself what you believe.”

There is little time for the Jones Boys to enjoy their new lease on life as they find the Grail’s final resting place swarming with Nazi soldiers and lackeys, trying to find their way through a maze of booby traps. When our heroes are re-(re-)captured, Henry is shot by Donovan in an attempt to force Indy to navigate the inner workings of the Grail castle and retrieve that most sacred of artifacts. Indy avoiding the deadly traps of an ancient fortress is a callback to the opening sequence of Raiders of the Lost Ark, as well as a means of communicating how, finally, Indy and his father are connected. The audience’s memory of Raiders also lets us know how high the stakes truly are in this moment. This is no adventure for a golden idol in which some fast running, whip-swinging, and a well-placed seaplane can guarantee a safe getaway. This is a battle for the life of Indy’s father and against the forces of darkness, and the Jones’ mutual ability to traverse these ancient obstacles is a testament to their bond and the peril they find themselves in.

As Indy goes deeper and deeper into the castle depths, he encounters deadly trials that could lead to a fall to his death or decapitation. It is only through the understanding of the Grail Diary and his father that Indy is able to navigate these tests of faith. Although Indy has seen the power of the supernatural on numerous occasions, he could never be described as a person of deep faith. His father on the other hand, is driven on a quest for the Grail because of his faith, and he is able to share that with his son in this paramount moment. With his father near death, knowing his only hope is to reaching the healing power of the Grail, Indy is able to take that final leap and reach the innermost sanctum.

Guarding that sanctum is the Grail Knight, and the encounter with that immortal guardian is one of the most fascinating scenes in the franchise. The Knight is a character right out of myth; a faithful guardian, grayed by the centuries, waiting for his successor to come and take up this sacred duty. He is as far away from the historical crusader knights in morality and faith as Henry Jones is from Walter Donovan, but that is why he was chosen for this task. He was the only one who had the same faith that brought Indy to this place. The Knight is even canonized in his final shot near the end of the film. As the stone edifice around him collapses, he waves farewell to the world, framed as a medieval portrait come to life.

Belief in the power of the Grail is not enough however. As Elsa Schneider and Walter Donovan enter the Grail’s sacred resting place, they make their intentions clear: they want the cup. With the Knight’s immortal words of “choose wisely,” Donovan, urged on by Elsa, chooses the most aesthetically beautiful golden chalice and drinks deep from it. We are then treated to a spectacular scene of rapid desiccation and death (courtesy of make-up and effects artists Nick Dudman and Stephan Dupuis), as Donovan reaps the rewards of his poor choice and Elsa’s manipulation. Indy however, is wise and pragmatic enough to spurn any temptations for greed or power and chooses the “cup of a carpenter.” He is able to take the Grail back to his father and, holding him in a position reminiscent of a religious icon, helps him drink from the cup. In spite of his skepticism, Indy takes on the role of the saint giving healing succor to the sick and the dying. He may never be a religious man, but Indy drew strength from the faith of his father and their renewed love for one another and was able to heal him, physically and spiritually.

“Let it go.”

Nazis lack the morality and perspicacity of the Jones boys, however, and as the magic of the Grail causes the fortress that had been its home for centuries to crumble, chaos ensues. Elsa has witnessed the healing abilities and miraculous power of the Grail and can only think of how she can use it for her own personal gain. She tries to escape the fortress with it gripped tightly between her hands, but the further away from the inner sanctum the Grail travels, the more violently it shakes the very earth that shelters it. Despite Indy’s best efforts to save her, Elsa is swallowed up into rocks and fog beneath the fortress. Desperate to save the Grail itself, Indy risks plummeting to the same doom and reaches into the bottomless chasm for the cup. It is only with the urging of his father (who finally calls his son by his preferred name, “Indiana”) that Indy is able to “let it go” and let his father save him. It’s an incredibly touching moment as both men are able to meet each other as equals and as father and son. Their relationship has been resurrected thanks to the quest they have completed with one another and there is no more need for a physical artifact. Their love for one another is all the Holy Grail they will ever need. Cue the Joneses, Marcus Brody and Sallah riding off, literally into the sunset.

So maybe it’s my weakness for good guys saving the day and for great father/son stories, or my Catholicism influencing my opinions on Indiana Jones the way it influences how I view movies like The Exorcist and Cronos, but I can’t help but find Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade the most fun, fulfilling, and emotionally satisfying entry in the franchise. It has everything the other Indiana Jones movies have: a great score by the immortal John Williams, thrilling action sequences, Nazi-punching, excellent supporting characters like John Rhys-Davies’ Sallah and Denholm Elliott’s Marcus Brody, a fantastic female lead in Alison Doody, great villains in Julian Glover’s Walter Donovan and Michael Byrne’s Nazi Colonel Vogel. What set’s Last Crusade apart is the undeniable chemistry between Harrison Ford and Sean Connery, between father and son, and the increased psychological and spiritual import the film takes on from that relationship. Regardless of how Indy and Henry are different in temperament and religious beliefs, their journey to find faith in each other is the true crux of this film. So much blood has been spilled over religious wars, over the artifacts fought for in the Indiana Jones films, that it is a perfect culmination to this trilogy that this artifact helps bring healing to two characters who have been so broken, and broken by the obsessive search for those very objects. We, the audience, have journeyed with them as they find that love in each other, so we can celebrate in that ultimate victory because we love them too.

Film ’89 Verdict – 10/10