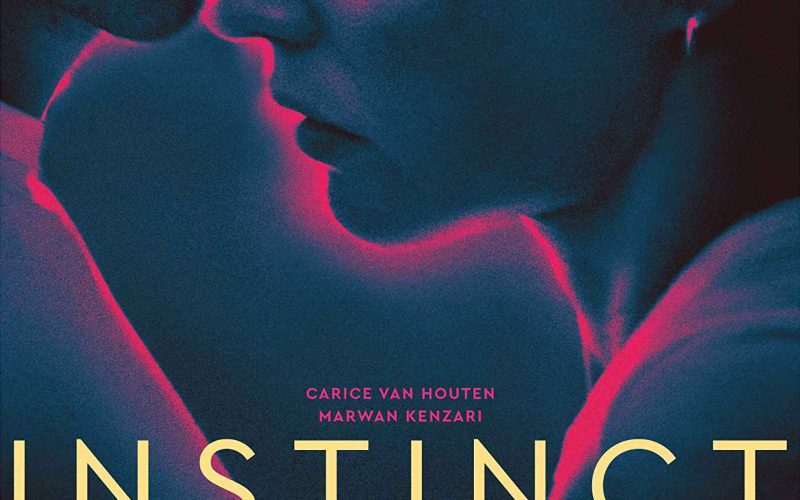

Instinct (2019).

Since I moved to the Netherlands I’ve been on a hunt for local film product, flicks I couldn’t have possibly seen back in the States. Conveniently the Dutch film industry has been pushing this movie hard, fitting it into as many theatres as it can possibly reach with the requisite amount of English-subtitled screenings. (It’s also The Netherlands’ entry into the Academy Awards Best Foreign Language category.) It’s a big deal to have uber-hottie Carice van Houten (Black Book, Game of Thrones) co-producing this inaugural feature with business partner Halina Reijns, an actor-turned-director whose relationship with van Houten goes back to the early 2000s. On paper, this is a dream team ready to play across the continent and beyond — two veteran actors beginning a new phase in their careers, using state funds from The Netherlands to make a piece of art which couldn’t have been created anywhere else.

Instinct is a gritty piece of filmmaking influenced by both social realism and Joe Eszterhas, if you can believe it. Van Houten plays Nicoline, a tough-as-nails psychologist in Holland’s carceral system working on rehabilitating hard cases so they can be released into society. The movie starts with a halfway brilliant fakeout, where you see the riot squad about to bust down the door to a cell holding Nicoline, where she’s poised like a sinewed jaguar ready to rip some faces off. They come at her hard, and she fights like the dickens trying to take out as many of them as she can. After she’s forcibly apprehended and relocated to a secure pen, it’s revealed this was a training exercise. It’s great storytelling, economically revealing she’s a strong, savvy vet of the penal system ready for anything it might throw at her.

Nicoline is a sharpshooter in the eyes of her colleagues, case workers trying to extricate some poor souls from their compulsions and bad decisions so they can salvage a normal life. She has friends among the staff, but it’s apparent that no one really knows her intimately. When she goes home, it’s to a generically decorated apartment which suggests a furnished rental. There’s no personal statement, no fingerprint or imprimatur. She appears to be all about the work — and in so showing, director Reijns and screenwriter Esther Gerritsen hint at a vacuum at the center of Nicoline.

In one quizzical sequence, Nicoline finds a middle-aged lady in her apartment when she comes home, baffling the audience until it’s revealed to be her busybody mother. Nicoline is able to relax in her mother’s soothing embrace, finding comfort in sleep until she wakes in the middle of the night to find mom spooning her, entirely bare-ass naked. There’s a moment of acknowledgment about how weird this is, but the edit lets it go by fast as if not to overwhelm us with too much psychology just yet.

We’re familiar enough with our protagonist now, so the filmmakers roll out her opposite number, Idris, a lithe Moroccan-Dutch man, in the system for a rape. He’s what we call a “sex offender,” which happens to be Nicoline’s professional speciality. Idris is one of those hard cases she’s been training to deal with, a slick operator with tons of sexual charisma and the intelligence to use it. He’s been inside for a few years now, reforming after perpetrating a brutal attack in his youth — and now he’s on the precipice of unaccompanied furloughs into the world. The guy has to merely behave for a few more weeks and he’s home-free.

But Nicolina sees a player at work — she interviews him and knows that he’s running game, performing the role of a penitent man atoning for his transgressions. Her coworkers don’t see it, and they advise he’s ready for weekend release. She digs in her heels, insistent that they’re making a mistake but no one agrees with her.

Now van Houten is 44 years old, a familiar figure in feature filmmaking since the late 1990s. She cuts a fearsome figure, not just because of the strength of her performances, but also due to being exposed by any number of sexy roles which have required full frontal nudity. We know where we stand with her as an actor — her range and boldness is not in question.

Contrast that with 36-year-old Marwan Kenzari, the actor tasked with going toe-to-toe with van Houten. He’s a new quantity to me, this being my first experience with him in spite of him having supporting roles in such studio films as Kenneth Branagh’s Murder On the Orient Express and Guy Ritchie’s live-action adaptation of Aladdin. I’m not saying this guy is a bum, I’m just saying that I’ve never seen him before — and you have to bring some heat if you want to share the screen with Carice van Houten.

The film becomes a tete-a-tete between the two, as Idris begins his charismatic hustle of Nicoline. She’s trying to crack him to find the fiend inside, and he’s trying to separate her from her slimming trousers. As much as she’s repulsed by his crime and the kind of man he is, there’s a sexual spark.

In an earlier scene where she’s on a date with a coworker, Nicoline initiates sex with dramatic submission, begging to be dominated by a dude clearly uncomfortable with the request. The audience has been introduced to her inner nature so the stage is set to watch Idris work on her in ways even she might be prepared to fend off. Nicoline asks probing questions in therapy sessions and Idris puts up a wall of some performed compliance with a fair amount of counterprobing, his own interrogation. He can smell the whiff of sex on her, that chemistry thing between the two which can fit together like clockwork. Idris can win both his freedom and a sexual conquest if he can steamroll Nicoline’s resistance.

In an earlier scene where she’s on a date with a coworker, Nicoline initiates sex with dramatic submission, begging to be dominated by a dude clearly uncomfortable with the request. The audience has been introduced to her inner nature so the stage is set to watch Idris work on her in ways even she might be prepared to fend off. Nicoline asks probing questions in therapy sessions and Idris puts up a wall of some performed compliance with a fair amount of counterprobing, his own interrogation. He can smell the whiff of sex on her, that chemistry thing between the two which can fit together like clockwork. Idris can win both his freedom and a sexual conquest if he can steamroll Nicoline’s resistance.

And therein lies the flaw in this film, at least for me. What the director works so hard to define in the earliest beats of the film becomes undone relatively easily by a character essayed by an actor with half the stature of van Houten. The careful delineation of personal and professional with Nicoline; her canny skill at navigating the vagaries of the penal system; her delicate care of damaged wards of the state… it’s all tossed aside because he flashes bedroom eyes at her.

It’s worth reemphasizing that the director/producer/writer team making this movie is all female, pros with many decades of experience behind them — thus for a sexy movie it avoids the male gaze. The examination of sex is strictly through female eyes. The camera may catch Carice van Houten in sexual situations, but she’s never an object of lust. If there is one, it would almost certainly be the handsome Kenzari. You can understand how Nicoline might be physically attracted to a well-built dude like that, but the step too far is how she could throw good judgment over her shoulder for an electric thrill. But such may be the difference between me observing sex in this situation, and the manner in which a female filmmaker might intend for it to appear to a different audience. C’est la guerre.

Regardless of what I might take as implausible, the final sequence of Idris showing up at Nicoline’s apartment on his unaccompanied furlough is devastating. This is what his targeting has been building up to, a sexual siege – flattening her resistance, pushing past her objections. He forces himself on her, truly believing that she was “asking for it,” as she sobs and begs for him to stop. Or is she? Is it roleplaying? We saw her request domination earlier in the story, so how are we to know concretely if this isn’t part of her fantasy? This is another component to the film which takes on a different meaning with a female director and van Houten herself steering the story as producer.

Idris pulls away before climax, satisfied that he’s made his point — he came and scored what he wanted, over her objections. He doesn’t read violation, only victory. If this movie has been building this as a contest of wills, he certainly thinks he’s come out on top.

Until… Shortly thereafter, back at the prison, Idris is expecting to be released into the world with the assent of the staff, and more importantly the word of Nicoline. She visits him in his cell and makes a move, indicating that it’s back on. She’s ready for some afternoon delight in the slammer, and Idris goes for it. While he’s midthrust, Nicoline hits a panic button she has mounted on her belt — and the goon squad drags him off, limbs flailing, howling in betrayal. Game, set, and match.

I mentioned social realism and Joe Eszterhas up front, and I see both of those elements in the way Halina Reijns observes the inhabitants of the carceral system, as well as the convolutions of female libido. Eszterhas, as we all know, was the screenwriter responsible for many of the lurid sex dramas of the 1990s including Basic Instinct and Showgirls. (Not for nothing is it worth pointing out the Verhoeven through-line from those works to Black Book, which featured both Reijns and Van Houten in the cast. Also, look at the title of this movie!)

Reijns is examining sexuality in a frank way, using it as both a stiletto and a maul via the complex character of Nicoline. It’s a successful examination, due to how brawny van Houten can be on film. She’s a fantastic actor who sells nearly any scenario with her movie star charisma. It makes up for the gulf between her and Kenzari, and ultimately is the selling point for film. You know what you’re getting from an actor of her caliber.

Film ’89 Verdict – 7/10

Instinct (also known as Locus Of Control) is in theaters in The Netherlands, presumably with a streaming rollout planned for Oscar season.