Is Hollywood’s Sequel Syndrome & Franchise Fever really such a bad thing?

The oft-made assumption that sequels are inherently a bad thing, something that may either be harming the creativity of the film industry or be proof of its lack of, is incorrect. It’s an easy assumption to make, however, and it’s one I believed for a very long time. Film is far too big to crumble under the weight of a mythical flaw that suggests the current proliferation of sequels and franchises may be destroying the movie-making landscape as we know it.

The box office numbers are lower, but the gap between the top earners and the mid-level films is exponential. People are going to the theater less which means they’re more likely to spend their money on a sure thing. There’s no doubt that exposure plays a monumental role in the belief that Hollywood has run out of ideas. There’s definitely some merit to that argument by way of the bizarre executive decisions that lead to news of a Memento remake, or the continued attempts to turn videogames such as Uncharted and The Last of Us into big screen blockbusters.

The fact is that audiences will spend their money if that film is perched on the shoulders of a beloved character or it’s set in a world that millions adore and the studios know this. A good example of the latter is 2016’s Fantastic Beasts and Where to Find Them, a film I recently revisited and found more enjoyment in than I did the first time around, but which still bares the flawed marks of a story that’s been bloated by decision-making from upstairs.

On one hand Fantastic Beasts is a light-hearted, wonderful little fantasy adventure about a wizard in 1920’s New York searching for a bunch of escaped magical creatures. On the other it’s possibly something more sinister; a forced attempt to create a franchise. Fantastic Beasts grew firstly from one film to two, then into three and before long five films had been announced before the first had even reached the big screen. Strip away much of the film that had laid out the groundwork for the four sequels to come and the movie is not damaged one bit. The point here is not to chastise this approach because if the remaining films take a similar, serialized structure, with solo adventures taking place within an overarching plot, then it’ll likely shape into a unified and rewarding experience. The opportunity to spend more time in an escapist universe with an already established audience is a win-win for both its fans and those whose pockets are going to be filled.

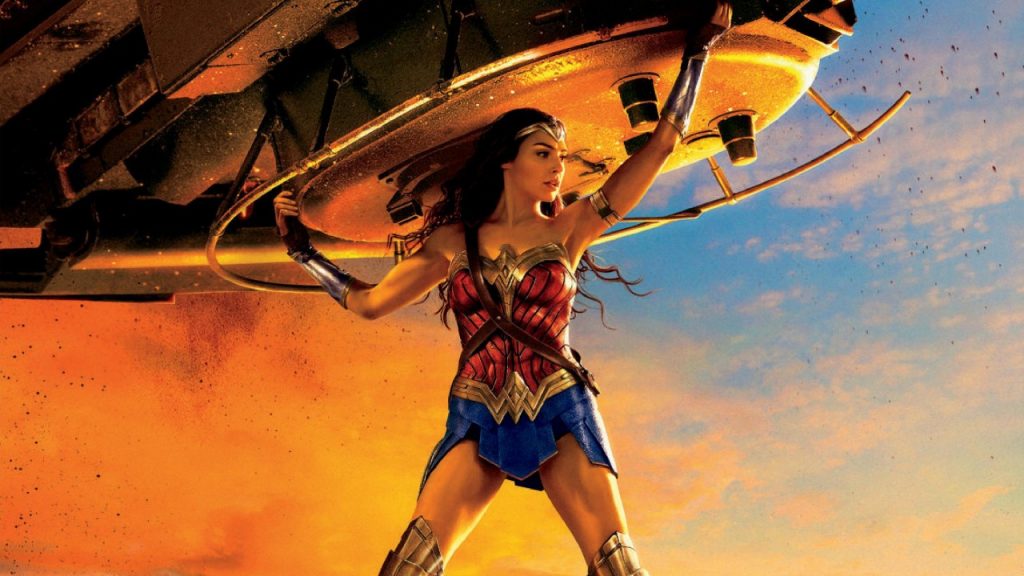

What’s integral though, is that it’s handled with finesse. The idea that a franchise will end once its story has been sufficiently told is a folly. There will be, in many cases, more story to be told as long as that story is making money. Some studios stubbornly continue to bulk up the calendar under the presumption that the future is filled with guaranteed success. Paramount’s Monsters Universe springs to mind. The DCEU over at Warner Bros. is a clear example of how a franchise no longer needs to truly earn its status – it only needs to capitalize on the adoration other storytellers have earned. DC’s output has so far been poorly received critically, the exception being this year’s Wonder Woman, but there hasn’t been a box office failure out of the lot. It begs the question, at what point do these numbers start to dwindle?

The evolutionary pattern of franchise films and big blockbusters in decades past seem to have made things infinitely easier for the producers of today and given them plenty of fuel for each studio’s entries in the blockbuster season. And yet Fantastic Beasts seems like a bizarrely natural progression. A recent trend, fittingly starting with Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows, saw studios splitting the climactic chapters of its property’s source material into two parts, to squeeze the remaining pennies from the franchise. Fantastic Beasts is committed to bloating its story out to a five-film project. That’s a decade longer in the world J.K. Rowling brought to life so many years ago. It’s also not the first franchise in recent memory to wholeheartedly devote itself to a detailed roadmap. Marvel Studios still holds the crown in that department.

Today studios are obsessed with stretching out the life-span of its most crucial properties, and fans salivate over every new visit to the theater, to see these characters back in action for a new adventure. The Hobbit Trilogy showed us all that there’s a way to do it wrong, spreading a short book out over three huge films whilst the modern take on the Planet of the Apes shows exactly how to revitalize a dormant franchise in a way that feels fresh, creative, and relevant.

Sequels and reboots aren’t a new thing. As our recent exploration of reboots shows, Hollywood’s been churning them out for decades, but the sheer scope and expanding mythos that’s being gifted to beloved franchises can be one of the very best things about the world of film. And just like every new and “original” release, some work and some don’t. It’s the fine balancing act of artistic necessity and justification versus financial need and a desire to turn a quick profit that’s always the most important factor. Films like Suicide Squad prove that a poor film doesn’t always mean poor returns but when the right creative decisions within the same franchise are made, such as with Warner’s subsequent Wonder Woman, the benefits go way beyond the business.