Jaws (1975).

How do you find new and fresh things to say about a film that, like Star Wars, is so embedded in popular culture that audiences throughout the world are extraordinarily familiar with it? The answer it seems, is that you can’t. Or at least it’s very difficult to. But in the case of Jaws I’ll give it a go…

Steven Spielberg’s 1975 film adaptation of author Peter Benchley’s novel of the same name was, at the time at least, something of a gamble for producers Richard Zanuck and David Brown. The studio had paid $150,000 for the rights to the 1974 book which had been a huge hit. They hired young director Spielberg whose only other theatrical film had been 1974’s well received The Sugarland Expresss. The idyllic location of Martha’s Vineyard, Massachusetts, was perfect for the summer haven of the film’s fictitious Amity Island. Carl Gottlieb would assist Benchley in adapting the book. All they needed now was a cast, both human and non-human.

The ever reliable Roy Scheider would play former New York cop and land-lover, Martin Brody, with more than able support from Richard Dreyfuss as oceanographer Hooper, and Robert Shaw as the Ahab-esque fisherman Quint.

The film’s main protagonist would be realised in the form of two huge mechanical sharks, built at great expense. The question was, how would such a machine work in the sea and would it convince the audience? I shan’t dwell on the well documented failings of the mechanical shark – nick named Bruce by the crew, Spielberg has made no secret of how much trouble Bruce caused the shoot. That said, the shark’s failings led to the director having to find other more creative ways to shoot the film and halted the possibly premature reveal of the shark which only heightened the tension in the build-up to the eventual reveal. This fortunate meddling by the fates is one of the things that ultimately helped make Jaws such a successful and economical thriller. It’s not so much the things we see but that which is implied that supplies the fuel for much of the terror of Jaws. The old ‘less is more’ adage is played to full effect. Nowhere is this more clear than in the film’s now famous opening attack on poor Chrissie Watkins (Susan Backlinie) where we don’t see the shark at all, yet the scene remains wholly terrifying on a primal level.

It’s the focus on these primal elements, the vast unknown seas and the beasts that dwell within them, that strike a deep, unsettling terror in the viewer. 71% of our planet is covered in water. Whilst we can’t survive for long without water, we are land based creatures and aren’t adapted to live in the ocean. In many respects it’s a hostile and alien environment and a place that we can’t survive for any extended periods unassisted. If we can detach ourselves from our primal survival instincts and look at the oceans for what they are, they are undoubtedly places of great beauty and wonder, but when viewed from the perspective of the situation in Jaws, it’s a place where we’re very much temporary guests and ultimately, not very welcome ones outside of our role as food for the titular shark of the piece.

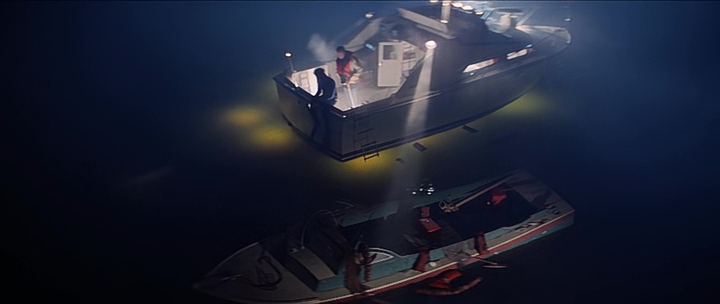

Early on in the film, Spielberg and cinematographer Bill Butler shoot the sea with a clear eye for enhancing its dark, mysterious nature. The opening attack on Chrissie Watkins is set at night with only moonlight providing illumination. Darkness and the water are used to stunning effect, again playing on our primal fears. Later on when two fishermen find themselves in a spot of bother when trying to bait the shark with a Sunday roast, again, darkness and water are blended perfectly to enhance the terror. In one of the film’s most efficient and memorable moments of terror, Brody and Hooper find the partially submerged wreck of Ben Gardner’s boat. Hooper, an oceanographer who, by very nature of his chosen trade, is free of the same crippling fear of the water that troubles Brody, dons scuba gear and dives to investigate. Again, this is a night time scene so darkness helps add to the mounting tension and the eventual jump scare moment as Ben Gardner’s head pops out of a rent in the ship’s hull, is as effective a scare as any other I can recall in a film.

Jaws, as we all now know, was a phenomenal commercial and critical success and the first film to clear $100,000,000 at the US box office. It also invented the concept of the summer blockbuster, the very term was created to describe the huge queues of film goers that would snake around entire blocks as they waited to see the film. But what makes Jaws such a great film? And make no (jaw) bones about it, Jaws is the very definition of ‘great film’. Well, in a nutshell, everything. Every individual facet of the film-making process came together to make Jaws a success; the exemplary cast, the lean script that dumped some of the book’s more unnecessary elements, the flawless direction in the face of adversity, Bill Butler’s stunning cinematography, Verna Fields’ masterful editing and the score.

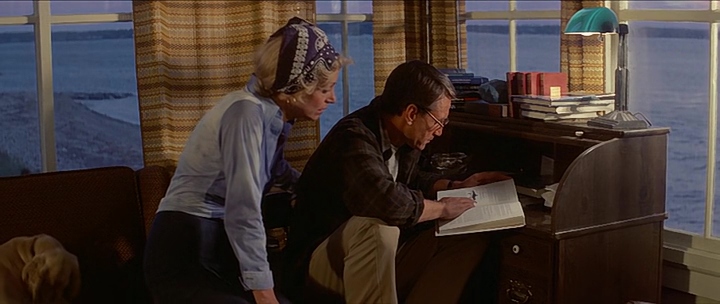

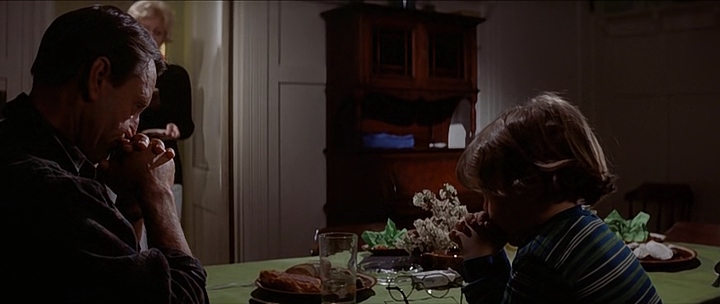

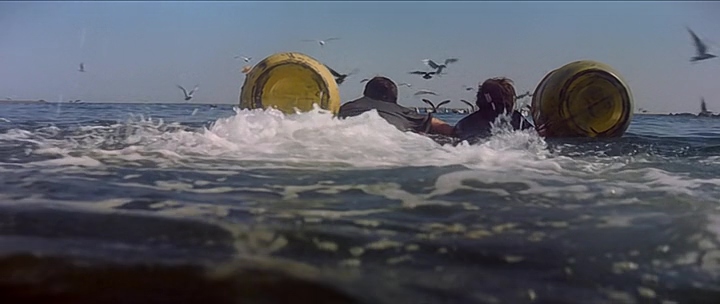

Oh yes, the score. Legendary composer John Williams will be long remembered for creating some of the most perfect and memorable music ever heard in films, from Star Wars to the Indiana Jones films, E.T. to Jurassic Park, but has he ever created a score more fitting, iconic and beautifully simplistic as that main ‘Duh duh, duh duh’ shark theme? When my eldest son (now seven) was three and a half years old he’d never seen Jaws (and won’t until I’m sure he’s old enough) but even then, as he does now, he associated that tune with a shark coming to get him. That’s how iconic Williams’ signature theme has become. And it’s not just the more tense themes either, the joyous music he created to accompany the thrilling barrel sequences and the more somber father/son dinner scene is some of his very best work. Without the score the film would no doubt lose a lot of its impact, which is testament to the genius of John Williams.

The cast all put in flawless performances. Much has been said of Shaw and Dreyfuss but here I’ll first focus on what I believe to be the true heart of the film, Roy Scheider’s perfectly believable turn as Brody. Brody is us, the everyman, the audience, the only one of the main trio of characters that actually fears the water. From his mounting concern following the grisly discovery of poor Chrissie’s remains to THAT beach scene, Scheider never once fails to deliver and convey the horror of what we’re seeing. But he’s not just a vessel through which our primal fears of the deep unknown oceans are channeled. His performance is one of the most underrated and well measured I’ve ever seen and he plays being drunk to perfection.

Brody is also the central protagonist around which the plot revolves, a hero who battles not just the titular shark but also the bullish and blinkered Amity officials such as Mayor Larry Vaughn (a brilliant Murray Hamilton) whose main concern is not the preservation of human life but the business brought in from Amity’s status as a summer haven for tourists and the huge revenue they bring to this small community. The scenes of Brody sparring with and being overruled by Larry are perfectly constructed in that they also act as a means by which exposition is delivered as when Hooper later arrives and tries to outline the very real threat this particular shark poses to Amity’s populace.

Peter Benchely was inspired by the play The Enemy of the People, by Norwegian writer Henrik Ibsen, which tells the story of one man trying to convince the local officials that the water in the local baths (which are a major source of income for the town) have been contaminated but he’s thwarted at every turn because the town is afraid that the cost of the repairs would be too high. Like Vaughan, the council in the play are more than happy to look the other way and to hope that the whole this is just scaremongering.

What Jaws does so well in this regard is to paint its central antagonist not as some evil supernatural force but as a very real force of nature. An animal of singular design, defined by its instinct to hunt, eat, thrive and survive. The great white shark has survived on Earth virtually unchallenged for millions of years and it’s lofty status in the animal food-chain taps into our own base survival instincts. We, as a species, may dominate the land but it is the shark that dominates the seas, a place we’ve scarcely explored and still know so little about.

As I did with my previous piece on The Terminator, where I used one scene to demonstrate everything coming together so perfectly in a film, for Jaws I’ll refer back to THAT beach scene. By that I mean the horrific attack on poor 11 year old Alex Kintner, a scene which in its perfect utilisation of a tension mounting build-up to the eventual horror and chaos of the attack itself, is as perfect a scene from both a technical and entertainment standpoint that I’ve seen. As we watch Brody, now more anxious and paranoid than ever, sat on the beach waiting and watching, Spielberg uses passing extras to cleverly mask zoom-ins on Brody. This adds to our sharing of Brody’s increasing tension and hits all the right parts of our subconscious mind and senses. We know that what we’re seeing is making us nervous. We know what’s coming yet the dialogue is virtually nil, it’s all done with perfect use of the camera, the framing, positioning and movement of and within shots, all perfectly constructed by Butler and later seamlessly edited together by Verna Fields. Then the moment comes and Spielberg hits us with the famous push/pull shot where we share intimately Brody’s moment of horrific realisation that the beach should have very much stayed closed. I defy anyone to show me a more perfectly constructed scene. It’s remarkable that at 27 years old Spielberg was giving us stuff like that in only his third film.

Obviously Jaws doesn’t just rely on technical brilliance. There’s a triumvirate of stellar acting talent in Scheider, Dreyfuss and Shaw that works in perfect unison bolstered by a near flawless script. Whilst Quint is diametrically opposed, in terms of the type of man he is, to both Hooper and Brody, the tense interplay between them makes for some thoroughly engaging entertainment on a scale that few films could ever hope to match. Quint is such an extreme character yet so much fun to watch and his demeanour is at best prickly, most times outright volatile. Yet it’s Quint’s expertise as a fisherman, played more like a hunter of the seas, that the other two men are, for the most part, wholly reliant on in order to carry out their task of ending this threat to Amity. If the famous and oft-parodied scene of Quint and Hooper comparing scars wasn’t good enough, it then leads to the even more famous USS Indianapolis speech, easily one of Jaws’ best scenes. Whilst legend suggests that Quint’s speech was completely ad-libbed by Robert Shaw, in reality it was conceived by playwright Howard Sackler, lengthened by screenwriter John Milius and rewritten by Shaw following a disagreement between Peter Benchley and Carl Gottlieb. Shaw presented his version of the speech and Benchley and Gottlieb agreed that Shaw’s final version should be used. Shaw first tried the speech actually drunk but nothing that was filmed was usable and a remorseful Shaw later tried it sober and nailed it in just one take.

Throughout the film there’s a subtext which would have been quite obvious to an audience in the mid ‘70s. The pitching of three very different men from different strata of society (Quint is working class, Brody is middle class and Hooper an intellectual, likely from a wealthy background) in a hostile and unknowable environment, against an unseen enemy on its home turf, is an echo of the Vietnam war. Soldiers from all walks of life were thrown together in an alien country against an enemy who knew the terrain intimately.

Just as the shark is the perfect organism, an eating machine as Hooper puts it, Jaws may well be the perfect film. It’s purpose, like that of film in general, is to thrill, move and entertain us and it does this without a single wasted shot or superfluous line of dialogue and it does everything it sets out to achieve whilst also completely redesigning the landscape of cinema. Without Jaws cinema would no doubt have been a different beast as we moved into a culture of big popcorn summer films with big ideas and bigger budgets. Yet as Jaws shows in one of its best scenes – Brody’s son Sean mimicking his father at the dinner table – Jaws is often about the quieter moments that don’t need words. Just a scene that will move any parent and gets across to us the predicament that Brody has found himself in. Was this moment scripted? No, but like much of the best moments in the film it came about due to the temperamental nature of that damn mechanical shark. Thank God Bruce didn’t always work.

For a film that starts so strongly and somehow maintains this level of quality for its duration, it’s the final act that brings Brody face-to-face with his and our own fears. Shaw meets a most grisly demise in a scene that still shocks and defies the belief that this film was given a PG rating. In the book Hooper died, but then again he’d been written somewhat differently and had actually had a brief affair with Ellen Brody, an unnecessary plot element that the film thankfully dropped. In the film he seems to die in the shark cage only to resurface after Brody later despatches the shark in that perfectly pitched confrontation, the prior set-up of a well placed oxygen canister providing a grandstanding pay-off. Once the sonofabitch has indeed smiled, Brody and Hooper are reunited.

I’ll bring this piece to a close by sharing a feeling I get every time I watch Jaws. Right at the end as I catch my breath and move back off the edge of my seat as Brody and Hooper kick their way back to dry land on a makeshift raft, there’s an air of calming serenity as Williams’ score becomes optimistically uplifting. It’s here that I have the same recurring thought, “That’s the best film I’ve ever seen.” Whether it is or not is a matter of personal opinion and I’m not saying it necessarily is but no matter what, that’s the feeling I’m left with every time I watch it. It’s as perfect a film as I’ve seen. It shouldn’t have worked and I’m sure for the majority of the shoot, all involved thought it would fail. Yet out of that adversity the cast and crew came together, ably steered by a young director who was firing on all cylinders, and they gave their all, the end result being (as Spielberg himself once described Lawrence of Arabia) a miracle of a film and a piece of art that I feel, more than any other film, perfectly encapsulates everything one associates with the word ‘movie’.

I’ll bring this piece to a close by sharing a feeling I get every time I watch Jaws. Right at the end as I catch my breath and move back off the edge of my seat as Brody and Hooper kick their way back to dry land on a makeshift raft, there’s an air of calming serenity as Williams’ score becomes optimistically uplifting. It’s here that I have the same recurring thought, “That’s the best film I’ve ever seen.” Whether it is or not is a matter of personal opinion and I’m not saying it necessarily is but no matter what, that’s the feeling I’m left with every time I watch it. It’s as perfect a film as I’ve seen. It shouldn’t have worked and I’m sure for the majority of the shoot, all involved thought it would fail. Yet out of that adversity the cast and crew came together, ably steered by a young director who was firing on all cylinders, and they gave their all, the end result being (as Spielberg himself once described Lawrence of Arabia) a miracle of a film and a piece of art that I feel, more than any other film, perfectly encapsulates everything one associates with the word ‘movie’.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 10/10