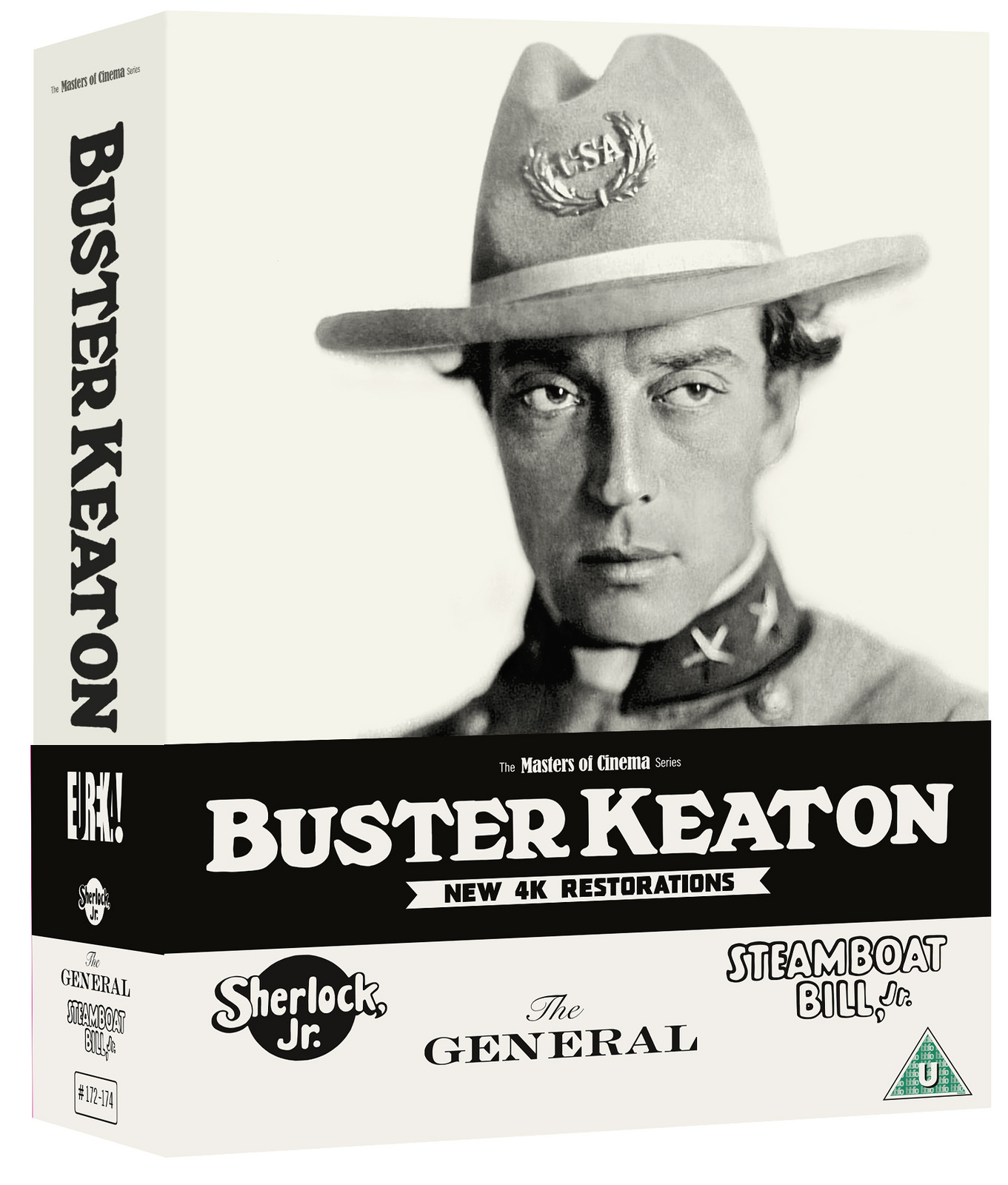

Masters of Cinema Buster Keaton Collection: Part 3 – Steamboat Bill, Jr. (1928) – Review.

For the final film in our look at the recent Eureka Masters of Cinema Buster Keaton Collection we have the 1928 masterpiece Steamboat Bill, Jr., a film which marked the end of Buster Keaton Studios and was the great man’s last independent production.

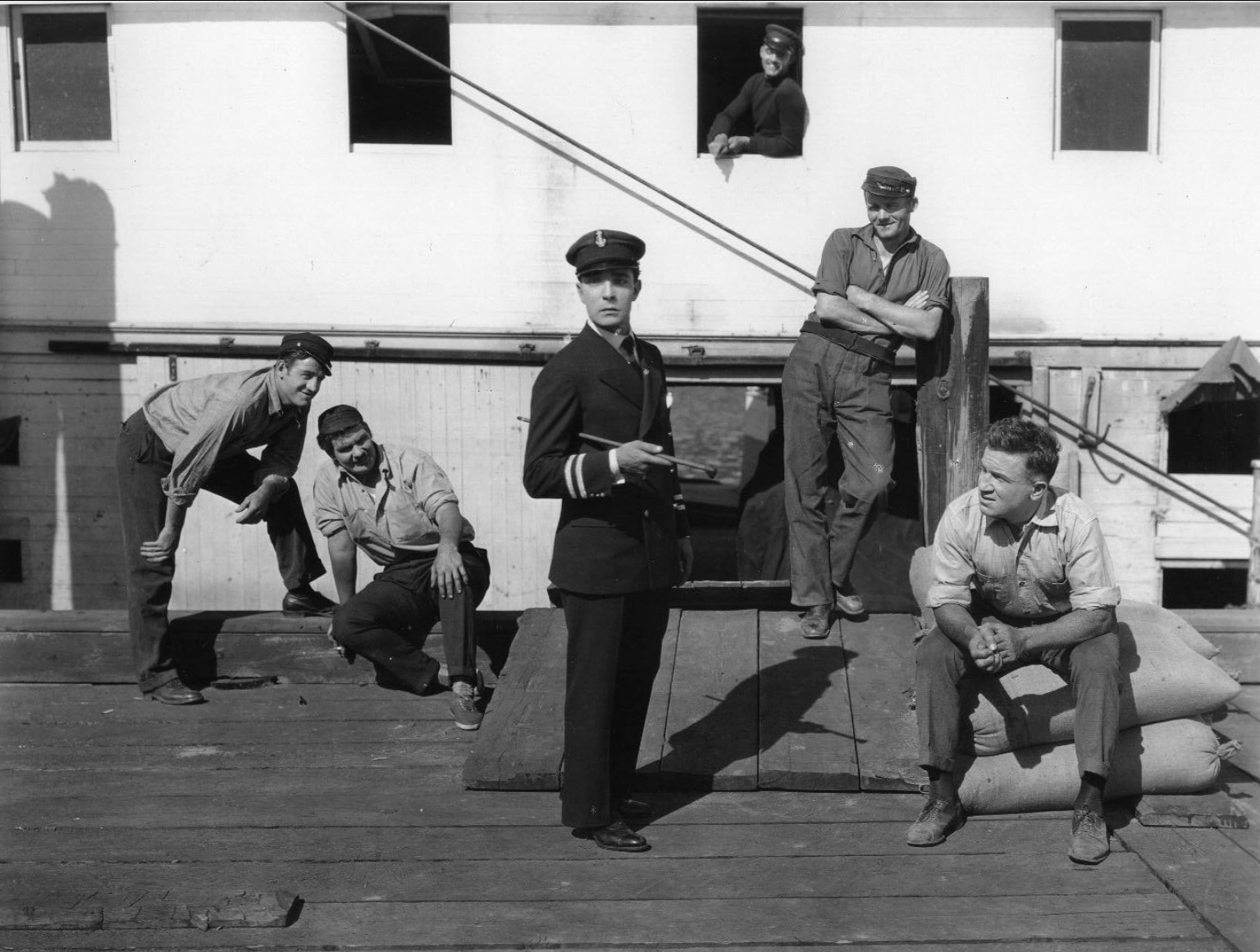

Directed by Charles Reisner, Steamboat Bill, Jr. tells the story of a young man (William ‘Bill’ Cranfield Jnr – Buster Keaton) who, having finished his schooling in Boston, goes to work with his father on the Steamboat Stonewall Jackson in the small town of River Junction. His father, played by Ernest Torrence, who hasn’t seen his son for many years, is expecting him to be a big strapping man just like he is. Instead he’s disappointed to discover that his son is small, hapless and a bit of a dandy. He wears fashionable city clothes, sports a rather silly pencil moustache and carries a ukulele with him.

Also arriving in River Junction at the same time is Kitty King (Marion Byron), Bill Jr’s school mate with whom there is a mutual attraction. The problem is, her father – John James King (Tom Mcguire) is the richest man in town and has just launched a luxury steamboat to rival the Stonewall Jackson. Basically, Kitty’s father wants to put Bill’s father out of business. What’s more, neither father wants their child cavorting with the child of their enemy.

After the masterpieces of Sherlock Jr. and The General, expectations were very high for this film. It is the only film in the set which I hadn’t previously seen and I was concerned that it wouldn’t stand up to the others. I needn’t have worried.

Steamboat Bill, Jnr. is of course full of the usual brilliant slapstick. There are moments when Keaton’s athleticism is spellbinding, especially when he is bounding around the boat in a way that would make a free runner clap in appreciation, and these are the least of his stunts!

Perhaps the most famous moment comes towards the end. A huge hurricane hits River Junction, houses are being blown to pieces, people are running for cover and Bill, who has suffered a head injury, has been left in hospital all by himself. As he lies in bed, the whole building rises off the ground revealing our hero. He then runs for cover but everything is closed. And wherever he goes the buildings seem to evaporate around him. Then we have one of the greatest, most dangerous stunts ever conceived.

Keaton steps out in front of a house and the whole front edifice topples down on top of him. Luckily, where he is standing is the exact position of an upstairs window so the house falls around him and not on top of him. Keaton walks away without a scratch.

This wasn’t a new stunt. Keaton had originally stolen it from a Fatty Arbuckle short (which co-starred Keaton) called Back Stage and had used it himself in the short film One Week. This time, however, the stunt was bigger and the wall much heavier. If he had been only a few inches either side, he would have been killed. Many have asked why he would have attempted such a dangerous stunt. One suggestion is that he was suffering from depression at the time after the break-up of his marriage, but when asked years later, Keaton just agreed that he must have been mad to try it.

Another famous scene is when he tries to take hold of a tree for safety only for the whole thing to be ripped out of the ground and carried high into the air before plummeting down into a river. This was done by lifting the tree up into the air on a giant crane with Keaton desperately hanging on the bottom. At the time of filming, many companies would shoot scenes twice in order to produce two prints, one for the home market and one for the international market. Some of the more dangerous scenes were often filmed with two cameras, but this stunt seems to have been reshot, meaning that Keaton was sent hurtling through the skies at least twice!

What holds the film together though are the characters. Keaton is his usual deadpan self, whilst all the other characters are performed marvellously. I would also single out Ernest Torrence and Tom McGuire if only for the sheer joy they seem to take in their one-upmanship.

Like The General, Steamboat Jr. was not a financial success, grossing less that its $400,000 budget and, as a result, his long-time producer Joseph M. Schenck, decided to dissolve Buster Keaton Productions and go to work for United Artists. Schenck encouraged Keaton to sign a contract with MGM (where Schenck’s brother worked) which he did. Years later Keaton remarked that this was the worst decision of his career and, although he made a few great films there (The Cameraman being the best) by-and-large, they were not up to the quality of his independent films and marked the start of the end of his career as a major star.

The 4K restoration of Steamboat Bill, Jr. is top notch and there is a great new score by Carl Davies. There are only a few extras – a short making-off video essay and a 55 minute audio recording of an interview with a 63 year old Keaton – but they are both interesting and informative. All in all this is another worthy entry in what is arguably the best Blu-Ray Boxset of 2017.

Film ‘89 Verdict – 9/10

The two previous entries in the series can be found:

Sherlock Jr. – here

The General – here

The Masters of Cinema Buster Keaton Collection is available on Blu-Ray now.