My Neighbor Totoro (1988).

Coming to Hayao Miyazaki’s early work as an adult, there’s something mildly unsettling about the titular creature of his beloved 1988 animated feature which turns 30 this year, My Neighbor Totoro. Its maniacal grin is only topped by the freakishly large-eyed Catbus, a frightening invention that I know myself, as a child, would not ever have gone near.

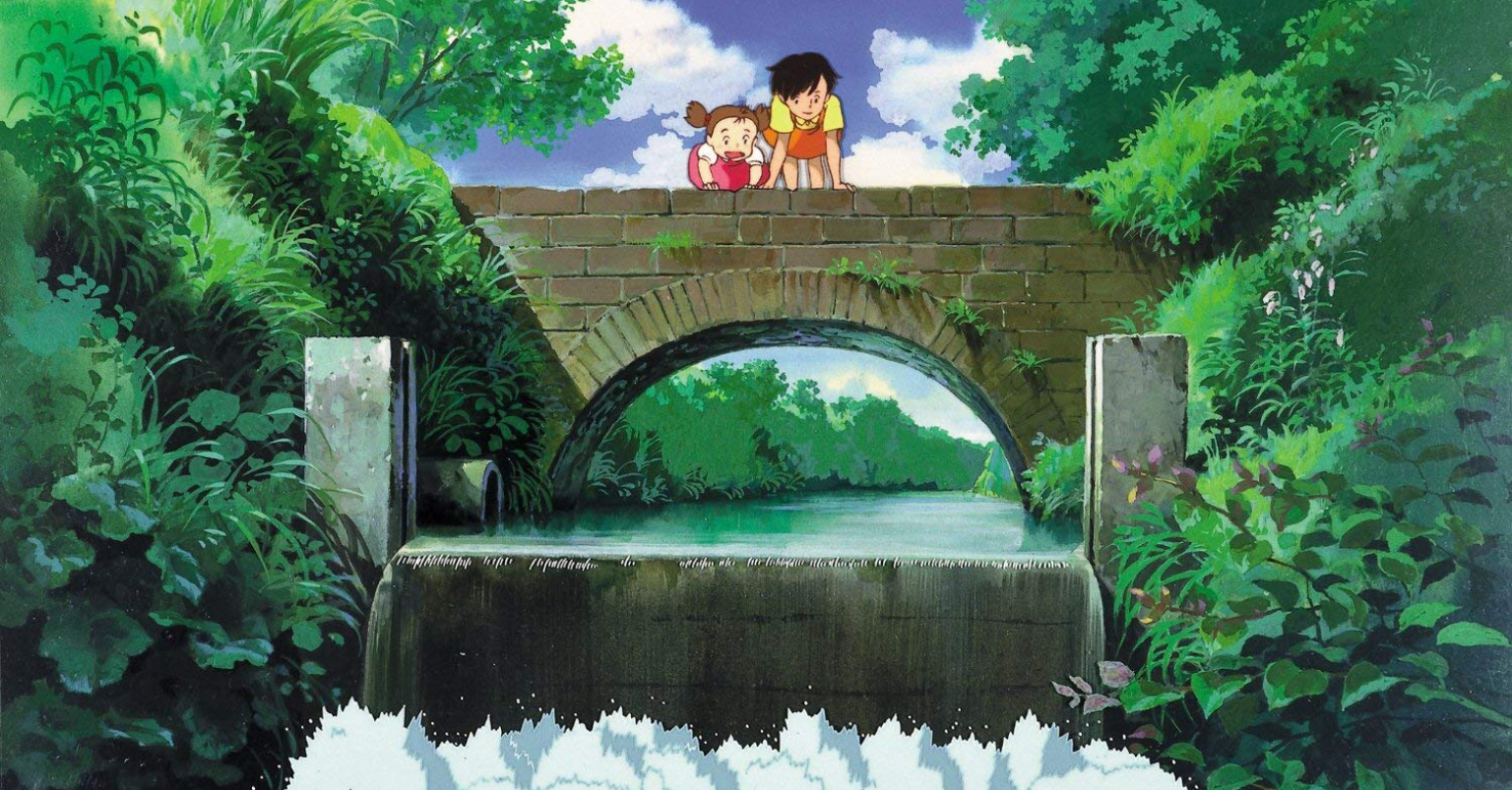

And yet the movie isn’t scary. It’s a whimsical fairytale, a joyous story about two girls and their father as they settle into a new neighbourhood. There really isn’t a whole lot more to it. They spend most of the film’s runtime clearing out the cobwebs of their new, broken down home, visiting their mother in the hospital and becoming familiar with their gorgeous, blissful surroundings.

My Neighbor Totoro perfectly captures the wonder and awe of being a child, of the feeling of discovery and the way in which we react differently depending on how old we are when we first come to them. The girls arrive at their new home and the first thing they find is a rickety, rotting support beam, and they begin to tempt fate by pushing and pulling at it with wholesome smiles on their faces. They proceed to spur each other on when confronting the darkness of the attic, a fear that all children have known. When the younger one is frozen in place, the older sister feels she must take the initiative. They encounter the first of the film’s fantastical elements here, in the form of Soot Spirits. They’re the little dust particles that make homes of empty spaces and scatter at the first sign of light and life. It’s an element that Miyazaki employs in later works.

There is no conflict at the forefront of the narrative – not in the way that we’ve become accustomed to in any case. There’s no driving force behind the story, and that should mean that it fails in its primary duty. Instead, it invites us into its lovingly crafted, idealistic world, a place where no ill will is shared when two children wait hours upon hours into the late night for their father to return home, or when a missing child is found and not ridiculed for her foolishness. Indeed, this is a world where children can venture out at their leisure, an inconceivable notion in today’s world. This one is more eutopic in that sense, and the difference between the two has only become greater in the thirty years since Totoro was released.

Satsuki is the older of the two girls. She’s picked on by a local boy who knows no other way to share his feelings. Satsuki feels a responsibility for her little sister but eventually can’t hold her emotions at bay any longer. Mei is the younger sister, modelled on Miyazaki’s niece; this is a common trait of his, often inspired to utilise those around him and let them bleed into his work. She’s four years old, adventurous, naïve, full of great ideas that are really quite poor ones. The film becomes most tense when she goes missing. She’s run off to the hospital on a noble quest, and become lost along the way. The film teases a dark turn, but by this point Miyazaki has earned our faith. There is no real threat outside of what the imaginations of two young girls can conjure.

To counteract their fears (most prominently for their mother’s health), in comes Totoro. The enormous, furry, magical creature shows up far rarer in the film than you might expect, and yet every scene he’s in is astonishing. We first meet him (assuming it is a he) when Mei happens into his home and falls asleep on his stomach. The next we see of Totoro is after some time has passed. In that time there’s no sense that Mei is being undermined or condescended by her father and older sister, who happily accept the existence of this supposed guardian in the forest. Again, there’s an abundance of skill in the absence of conflict, and how it works in the story’s favour. It’s a testament to expert craftsmanship, a masterful blend of music, art, and dialogue creating a day in the life with an otherworldy incision of surrealism.

Totoro joins the two girls at the bus stop later on, after it’s begun to rain. Satsuki gives the large creature an umbrella, and the sound the rain makes against the plastic makes him giddy with excitement. At this point in the film the smile is glued to my face. There’s little to be said for the art that hasn’t been said before. Just considering the hours upon hours of painstaking work that goes into hand-drawn animation enhances the experience of seeing it come to life. When Totoro shivers at the sound of the rain drops splashing against the umbrella, or when Satsuki sprints the length between the entrance to the attic and the window that when opened will light the darkness, it reminds us of fundamental experiences we’ve all had as children (and maybe even as adults too). And we know what it’s like to fall into an irrational meltdown of tears, or protest to bad news, hoping for the answer we wanted. At the very least, we hope for comfort.

By the time Satsuki hops aboard Catbus in search of Mei, and this freakish, smiling, seemingly sentient vehicle is flying through the countryside – unbeknownst to the grown-ups who are oblivious to its presence – we’ve completely bought into the fantastical despite how little of it the film actually has. By contrast, you mightn’t find characters more realistic than these in any film be it live action or animated. It’s essentially a string of tiny moments, on their own insignificant but tied together attentively and carefully so as to craft a complete picture of a small family, the members of which are defined so easily through their mannerisms and minimal dialogue.

Totoro himself remains a mystery. We might simply believe that he truly is the guardian of the forest (a half-baked idea according to Miyazaki), or maybe he is just another animal that’s made his home there. He sleeps often, we presume. Where he takes Catbus, late in the evening, all we can do is wonder. Does he exist to aid those who can’t fully fend for themselves, or did two girls stumble into his home, show him kindness, and simply earn it back? Miyazaki’s films are often infused with environmental themes. Here, it’s more subtle than in some of his other works, but it might be telling us that living harmoniously with nature can lead to a peaceful life. And, as the perfect first step into his folio of work, it’s as if Miyazaki himself is telling us to look around at the world we have, because it will surprise us at every new turn.

Film ’89 Verdict – 9.5/10

My Neighbor Totoro is available on DVD & Blu-Ray.