Patlabor 2: The Movie (1993).

Though the titular Labors are central to the franchise, you’d be forgiven for thinking otherwise after sitting down for the sequel to Mamoru Oshii’s feature film debut. Made to at least in spirit conclude the series, Oshii’s next film starts with a cold open taking place three years prior to the main plot. The only sequence that takes place outside of Japan, it features the destruction of the antagonist’s military unit when they’re ordered not to defend themselves and strike back against the enemy. And thus begins a layered political thriller soaked in the reality of post-WWII Japan and the significance of a country’s noncommittal international relations.

To fully appreciate the depths of Patlabor 2: The Movie, some understanding is necessary. This is a country still reeling from the aftermath of the second World War, and a combination of guilt, pacifism and apathy was at the fore of the national conscience from its leadership down to its citizenry. At the time Japan was being called upon by the United Nations to offer peacekeeping support overseas, creating angst amongst the public that would only worsen when deployed Japanese soldiers would perish overseas. It’s this lack of conviction that gifts Oshii the central themes of a film almost entirely devoid of the adventurous, light-hearted spirit of its predecessor.

Following the 1999-set cold open, we leap forward and become reacquainted with the main crew. However, the perspective is switched dramatically from the first film. Rather than following the exploits of Asuma and Noa, members of the Second Unit, Acting Chief Shinobu Saguma and Commander Kiichi Goto are now the leads. The scope is far greater as a result, with two characters through which we witness a political upheaval that they are both compelled to act on when pulled in by a government official. It all begins with the bombing of the Yokohama Bay Bridge, and leads all the way to an investigation of a conspiracy within the police force itself.

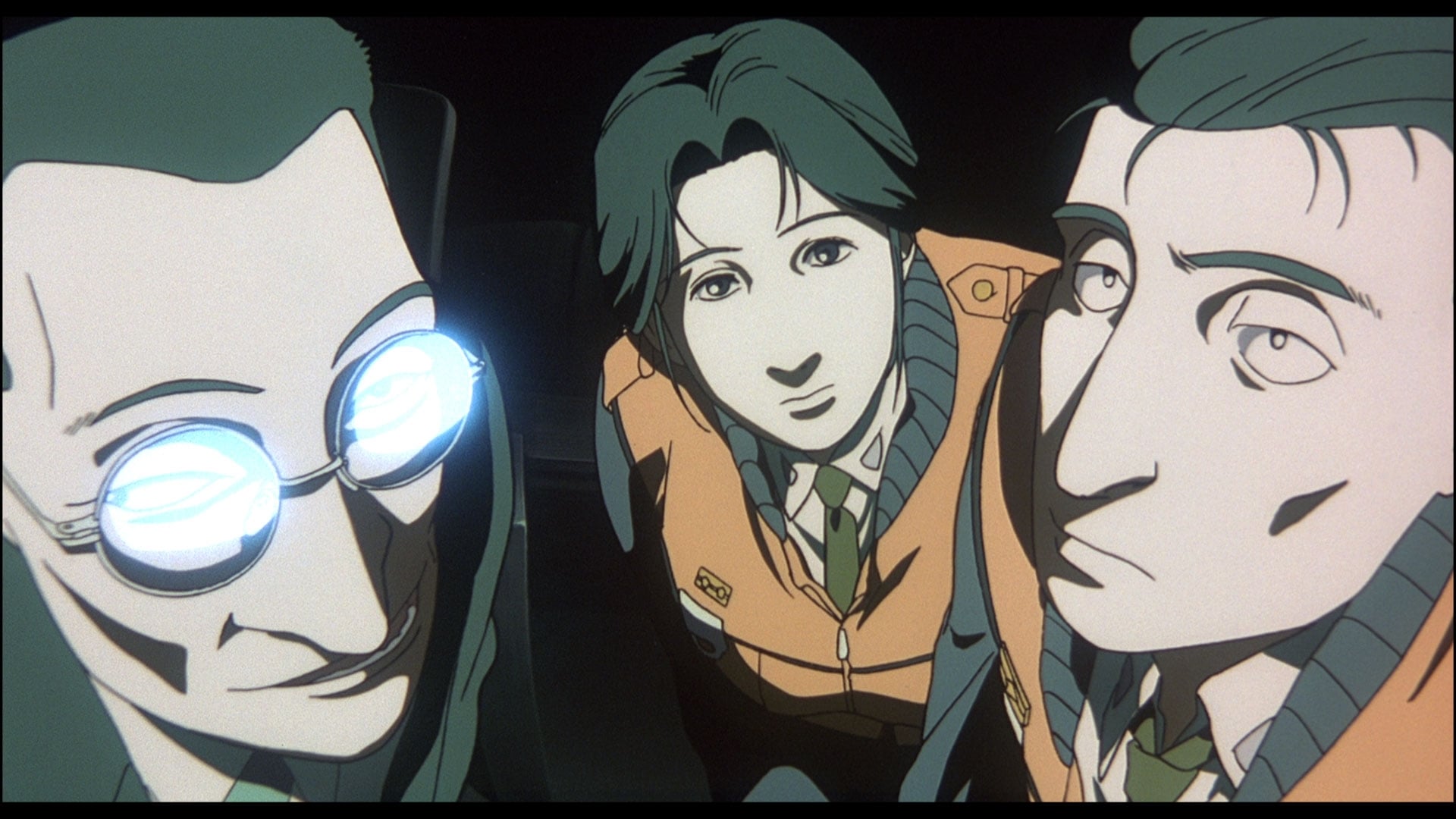

We meet Arakawa, a source from within the government who approaches Goto and Saguma with information relating to the complex nature of the crime committed. Arakawa explains that the entire thing was a false flag operation orchestrated from within the police force to shake the Japanese government out of apathy; only, the bombing itself was not a part of the plan. Instead, he theorises, this was the act of Yukihito Tsuge (the sole survivor of the opening scene’s massacre) and his group of terrorists. Tsuge’s motives are never made entirely clear; perhaps he’s fuelled by revenge, or maybe it’s something more. Arakawa monologues on the complexities of war during a conversation with Goto, questioning the uneasy peace Japan is experiencing by remaining aloof to international unrest. Oshii himself seems ambivalent towards all of this, given that he had prior to making the film protested against Japanese military involvement in peacekeeping duties abroad. It should be noted that at the time art created as a critique on national leadership was something of a risk, and there is evidence of the script saving face in cryptic, minute ways.

“What do we actually mean by peace?” Arakawa muses, suggesting that peace leads to war just as easily as war leads to peace. While Arakawa is significantly vocal in his critique, the character is made to appear untrustworthy. His malicious smile and devious eyes make for a suspicious character, and ironically he’s far less deserving of our sympathy than Tsuge himself. Tsuge is reacting to a country he seems hopeful of seeing make meaningful change. The prologue of sorts has him exit his destroyed Labor to look up at the face of a giant stone Buddha, worn and adorned with vines thanks to the passage of time; it stands as proof of the inevitable reality that civilisations will continue to fall and fade into history’s vast memory.

There’s far less theology and far more philosophy in Patlabor 2 when compared to Patlabor: The Movie. Debates on war and peace and commentary on Japanese politics are the cement between the bricks of this beautifully complex tale. It is a polar opposite experience to the character-driven drama of the previous film. Saguma’s is the character most personally challenged by the troubling turn of events in Tokyo, given her romantic history with Tsuge (who was her senior and, during their time together, married to another). This is described as the only blip in her otherwise accomplished career, and it’s suggested that this tarnished her ability to climb higher through the ranks. So when the time comes to try and capture Tsuge, she’s unknowingly used as a pawn. Her choices toward the end of the film are some of the only times in which we actually feel something. Most of Patlabor 2 is spent just trying to keep all of the moving pieces in order, so there’s a lack of emotional investment.

The inclusion of the SVII team members is an awkward necessity much like it was in the first film; they all play a significant role in the third act but are largely irrelevant prior to it. This is a sacrificial choice, as Oshii and his screenwriter do away with the staples of the franchise to raise the stakes exponentially. The phrase “ahead of its time” is used with a great deal of hyperbole these days, yet it’s hard to deny that viewing this film with a contemporary set of eyes cast attention to events that took place well after its release. In that sense, the film was incredibly relevant in relation to its Japanese audience at the time and its terrorist plot holds significant poignancy with an international audience today.

Patlabor 2 does a remarkable thing; it informs an attentive viewer on the fractured psyche of Japanese ideology at a very specific point in time while simultaneously remaining a stark reflection of a reality we still live in now. It is educational and riveting, dramatic and invigorating, and climactic but absent of a neat conclusion that would only act to disservice its overt realism. Mostly gone are the technological staples of the series, replaced by something maybe less visually rousing but far more lasting.

Film ’89 Verdict – 9/10