Quentin Tarantino’s first 25 Years, Part 1 – Reservoir Dogs (1992).

Getting Back To Work, Reservoir Dogs 25 Years On.

*** CONTAINS SPOILERS ***

For a quarter of a century Quentin Tarantino has been making and reaffirming his mark on the landscape of modern cinema. That 25 years of filmmaking began in 1992 when he made his feature length directorial debut with the incendiary Reservoir Dogs but Tarantino’s beginnings as a filmmaker go further back to his time working in Video Archives, a video rental store in Manhattan Beach, California where he learned his craft in a very unique form of film school.

Nowadays he has long since become an auteur director insomuch as his very unique style runs throughout all his films. He’s a director who has greatly influenced young filmmakers but who himself was deeply influenced by the films and filmmakers he worshiped as a young cinephile from behind that rental store counter. Quentin Tarantino’s knowledge and passion for film is vast. Both the director and his works are steeped in film lore and the influence of great directors and writers he admired and whom he would unashamedly homage and outright plagiarise such as Sergio Leone, Raymond Chandler, Akira Kurosawa and Federico Fellini. But aside from “the greats”, those filmmakers held in lofty regard by cinephiles, Tarantino had an equally strong admiration for more pulpy and often low-brow films, particularly exploitation cinema in its many forms. It could be argued that his films are most overtly influenced by the likes of Jack Hill’s Blaxploitation classics Coffy (1973) and Foxy Brown (1974), Asian cinema such as Ringo Lam’s City On Fire (1987) and the innumerable works of John Woo, Japanese animation and the vast array of Spaghetti Westerns that proliferated the ’60s and early ’70s. Tarantino’s influences stretch across a vast range of genres and individual aspects of his unique style can be attributed to many different filmmakers. Tarantino himself exists in his own self carved niche much like François Truffaut who was a film critic first and foremost who studied the likes of Alfred Hitchcock, Howard Hawks and John Ford before venturing forth to become a beloved and acclaimed director in his own right. Both Peter Bogdanovich and Martin Scorsese would follow a similar path of reverie as film lovers before making the move to become acclaimed filmmakers in their own right.

For his first venture into directing a feature film, Tarantino, who also wrote the screenplay, planned to shoot Reservoir Dogs on 16mm, in black and white with a budget of around $30,000. On acting duties would be Tarantino’s friends including his producing partner Lawrence Bender. It was then that Tarantino got arguably the most important break of his filmmaking career when the script landed in the lap of Harvey Keitel. It was with Keitel’s involvement that the budget was given a huge boost to an estimated $1.2 million (other sources state the budget was as high as $1.5 million). Keitel’s assistance extended to the provision of casting sessions in New York where several of the eventual principal cast were found. Of said cast, the notoriously prickly Tim Roth refused to read for his part and only after Tarantino took him on a heavy drinking session did he eventually read for the director.

Tarantino’s tale of a jewellery store heist gone wrong borrowed a key element from the 1974 film The Taking of Pelham One Two Three in that the criminals would all use colour-coded names such as Mr Blue and Mr Brown. Amongst the numerous actors who either turned down roles or auditioned unsuccessfully for Reservoir Dogs were George Clooney, Christopher Walken, Samuel L. Jackson, Robert Forster and David Duchovny. Cast as Mr Blue was career criminal Eddie Bunker who added a small but genuine bit of authenticity to proceedings and was on-hand as Tarantino’s unofficial technical advisor of sorts.

Following the 35 day shoot, editing of the footage was passed over to the late Sally Menke. Menke would perform editing duties on Tarantino’s first seven films until her tragic death from heat-stroke during a hike in Griffith Park in 2010. What Menke brought to the table as editor was an absolute and clear understanding of the fractured narrative structure that Tarantino would first employ in Reservoir Dogs and that would become a key facet of his auteur style in later films. The film opens with a pre-heist coffee shop discussion of the true meaning of Madonna’s Like A Virgin. This pop culture fuelled discussion then moves onto the etiquette of tipping waitresses and it is here that we are first introduced to another factor for which Tarantino would be renowned, the often lengthy and exquisitely crafted dialogue scenes. Any other filmmaker would soon segue into the heist proper but after the now iconic opening titles, perfectly matched to the tune of The George Baker Selection’s “Little Green Bag”, we skip forward in time to the bloody aftermath of the jewellery store heist with Mr White driving away a badly wounded Mr Orange. It’s here that the film’s perfectly crafted, beautifully edited yet wholly unconventional narrative structure comes into play. Now it’s been said that the omission of the actual bank heist from the film was originally due to budgetary reasons. This is something I find hard to believe as the fractured chronology of the screenplay is so perfectly precise and works so well from a point of how we are drip fed both plot and character exposition that it’s difficult to see how scenes of the heist would fit into the tightly woven story. It’s far more effective when left to the imagination and one of the factors that marks out Reservoir Dogs as so unique in the crime film genre.

As Tarantino himself has stated, these jumps in the story’s chronology aren’t flashbacks. Flashbacks are when a character thinks back on a past event and we, the audience, are shown that recollection. Here the past events we see are instead a restructuring of the narrative. This restructuring allows for the precise expositional delivery of such things as the relatively late reveal of who the rat amongst the group of criminals actually is. If told chronologically there would never be any tension as Mr Orange’s true nature would be revealed early on in the film thus robbing the story of much of it’s impact.

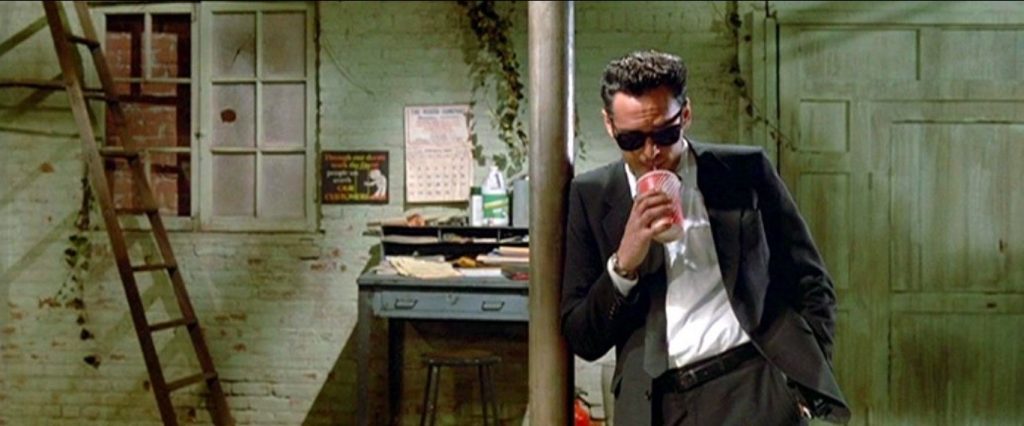

Aside from the flawless use of a jumbled but perfectly edited chronology and extended takes of memorable dialogue, Reservoir Dogs has some quite wonderful performances. Harvey Keitel is unsurprisingly on top form as the coolly efficient Mr White and Steve Buscemi is his at his jittery best as the snarky Mr Pink. Whilst this is very much an ensemble piece it could be argued that Tim Roth’s Mr Orange is central to the story as the undercover cop amongst the group of criminals. Roth seems to blend in amongst the group early on until his big reveal after which the narrative warps back in time to his pre-heist preparation. The scenes with Mr Orange learning and reciting the commode story, itself a story within a story within a story, are all about acting and performance and could be seen as Tarantino subtly celebrating the art of the actor’s trade. Of all the core players it’s Michael Madsen’s psychotic Mr Blonde who leaves the biggest impact. Whilst all of the criminals are brutally ruthless when the need arises, they only ever kill out of necessity and still adhere to some loose code of honour. Mr. Blonde observes no such boundaries as seen in his show of calmly gleeful sadism as he tortures Nash, a captured cop. Needless to say Madsen has never been better than he is here.

A stylistic choice that would become yet another of Tarantino’s trademarks is the perfect selection of songs in place of a traditional score. Nowhere is this better illustrated than his use of Stealers Wheel’s “Stuck In The Middle With You” which brings us on to yet another key facet of Tarantino’s work, the often shockingly brutal violence. Upon its initial release at Sundance and then theatrically in the US and in particular the U.K. where it was initially banned, Reservoir Dogs was the cause of some controversy surrounding its violence and in particular the infamous ear slicing scene. The scene where Mr Blonde is left to babysit the captured cop was the main issue people had with the film and it’s graphic depiction of torture. What’s remarkable about the scene is that the actual ear slicing itself happens off screen but reinforces the old adage that what is left to the audience’s imagination is often far worse than anything the filmmaker can show us. The aforementioned song choice, an especially uplifting piece of ’70s folk rock, is one that doesn’t naturally fit with the brutal tone of the scene and adds immeasurably to the viewer’s sense of sickening unease. What makes the scene even more hard to bear is how it is dragged out not by lingering on the viscera wrought by Mr Blonde but instead by Tarantino’s choice to follow Blonde out into the sun drenched L.A. street where he calmly gets the gasoline can from his car. The relative serenity of this brief outdoor segue gives us a moment to catch our breath but also forces us to linger on both what we’ve seen and also what further horror is to come. It’s a stunningly well conceived and effective moment that best illustrates the level of truly bravura filmmaking that’s at play here.

Another perfectly crafted scene is when, in yet another backwards jump in the narrative, we are shown what happens immediately prior to Mr Orange getting shot. After Mr Brown (played by Tarantino himself) crashes the getaway car and succumbs to a head injury, Mr White opens fire on a squad car killing the cops inside in a flurry of bullets and squibs. It’s Mr Orange’s reaction to this that is so devastatingly effective. By now we know he’s a cop and seeing him witness Mr White, for whom he has a clear level of respect and almost affection, so brutally dispatching men who may be colleagues of Orange’s and being helpless to intervene is one of Reservoir Dogs most subtly chilling moments.

The origins of the final three-way stand-off at the end of the film could be attributed to any number of films admired by the director but it’s a perfect end to the film. It leaves Mr White and Mr Orange badly wounded and with the cops off screen surrounding them we witness Orange’s final, fatal confession. Much can be read of this but I’ll leave that for you to mull over. The impact of Reservoir Dogs cannot be understated. It was a film that eschewed and subverted convention and was very much at the centre of the explosion of the independent film movement. It gave audiences something different to sink their teeth into than the common or garden blockbuster fare they were so used to and spawned a generation of cinephiles and filmmakers who may have never discovered the innumerable directors of generations past that Tarantino so openly celebrated. Whilst it was barely marketed in the US it was commercially well received elsewhere, especially the UK after its ban was lifted and it received something of a second run in theatres after the success of Tarantino’s stunning sophomore effort, Pulp Fiction. In the wake of Reservoir Dogs there was a slew of hip, violent crime movie copycats of varying qualities. Many had the same lo-fi sensibilities of Reservoir Dogs, most aped it’s cool soundtrack and pop culture reverie but none would equal its stature and all were to some extent lesser facsimiles but it shows how much of an impact Tarantino’s low budget indie film had made.

Whether you embrace Quentin Tarantino’s unique and sometimes self indulgent style or not it can’t be denied that he’s the very definition of an auteur filmmaker. He makes the films he wants to make, he doesn’t compromise in any way on his vision and sticks to his guns to deliver the films he wants to see on the big screen. His love of film and knowledge of the craft of filmmaking knows few equals and was apparent from the very start in his blistering first foray into directing. Citizen Kane is considered by many to be the greatest directorial debut of them all and few would argue against that but if one film were to give it some competition for that title it’s Reservoir Dogs. It kickstarted an entire film movement, made an indelible mark on modern cinema that’s still being felt 25 years on has lost little if any of its bite and vigour. It’s not only one of the greatest crime films but also one of the best films of the ’90s and the best thing is, with a film as good as this Tarantino was just warming up. Reservoir Dogs is a film whose quality belies its meagre budget and is every bit as good now as it was 25 years ago.

Film ’89 Verdict – 10/10