Quentin Tarantino’s first 25 years, Part 6 – Death Proof (2007).

“It’s better than safe, it’s Death Proof.”

*** SPOILERS ***

In 2007, filmmakers and longtime friends Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez embarked on an experiment that would look to pay homage to the double feature Grind House B-movies of the ’70s with their trashy, exploitation driven themes and low production values. The project, aptly titled Grindhouse, would comprise of two main features shown back-to-back. Rodriguez’s film, Planet Terror would be a schlocky, violent ’80s style science fiction romp. Tarantino’s segment, Death Proof, would pay homage to car films of the ’70s such as Vanishing Point (1970), Two-Lane Blacktop (1971) and White Lightning (1973) but with a good dose of the slasher flick thrown in for good measure.

Having played in theatres as a double feature for several weeks having been designed and marketed as such from the outset, exhibitors were reporting that audience members were leaving the cinema after the first feature, Planet Terror, not realising or likely forgetting that the second feature, Death Proof was still to play. One reason cited was that the majority of the audience was too young to remember when Grind-house theatres showed such double features. Ultimately the experiment was something of a commercial failure and proved that the double feature simply wasn’t something that modern audiences were familiar with and come the home video release, the two films were separated and padded out with excised footage into two full length features. So there you have in short form, the story behind the genesis of Quentin Tarantino’s sixth feature film, Death Proof.

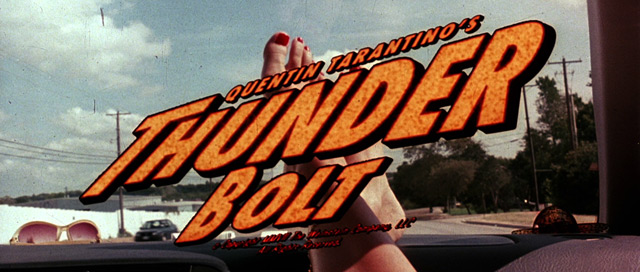

From the outset the aim was to make two movies that aped the low budget, B-movies of the ’70s and ’80s. Sharp, precision filmmaking of the kind we’d seen in Tarantino’s previous films was not the intention here. With Death Proof the auteur director was doing something unheard of, he was making an intentionally bad movie. Although it has a contemporary setting, it very much has the feel of those same ’70s/’80s B-movies. The film opens with a vintage “Restricted” animation warning the audience of its adult content which leads into the opening titles replete with a brief glimpse of a frame of the film’s “original” title Thunder Bolt before the crude, alternate “Death Proof” title card pops up in its place. If this reference isn’t lost on you then you should be roughly aware as to what kind of film this is going to be. In typical Tarantino foot-fetish fashion the opening credits also feature an extended shot of a woman’s feet on a dashboard. More shots of women’s feet will follow later in the film.

Much effort is made to authentically replicate the low-rent aesthetic with scratches, marks and frame debris on the print, telecine wobble on the title cards, bad jump cuts and missing frames throughout, mismatched background noise between alternating shots and worse still, different background locations between angles. On top of this you have ill-timed camera moves, disorienting pulls and zooms and all manner of flaws that a director as assured as Tarantino must really being going out of his way to do. At the 56 minute mark the film even temporarily switches to black and white. Strangely, with the black and white footage and also when the film switches back to colour, the print is clean and devoid of the scratches, dirt and debris from earlier, perhaps suggesting a film shot in two halves some time apart on completely different film stock and possibly trying to give the illusion that the first half was filmed by a different director.

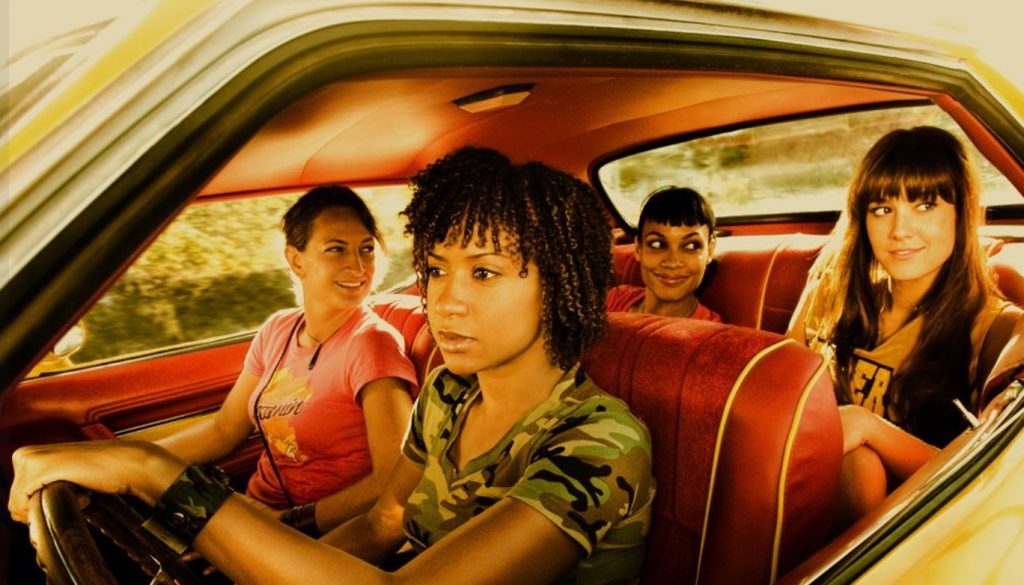

The majority of the second half of the film, from a technical standpoint, is actually impeccably well shot, like a conventional Tarantino movie, thus strangely eschewing the whole raison d’être of the film. It also features some incredible, often jaw-dropping stunt work that utilises wholly traditional stunt driving with none of the reliance on CGI that somehow seems acceptable these days. We are also treated to some hair raising stunt work from the amazingly brave and talented Zoë Bell as she plays “Ship’s Mast” on the hood of a speeding muscle car. Bell was the stunt double for Uma Thurman’s character of The Bride in Tarantino’s Kill Bill films and so impressed was he with her skill and prowess that the part in Death Proof was written only with Bell in mind with the stunt woman cum actress even playing herself. Zoe’s mission in the film is to drive a 1970 Dodge Challenger, the very same car from a film that clearly inspired Death Proof, the 1971 cult classic Vanishing Point.

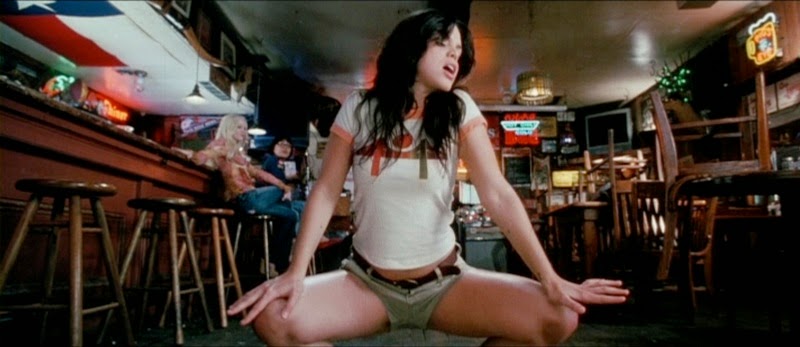

Alongside Zoë Bell, Tarantino assembles a great young female cast consisting of Rosario Dawson, Mary Elizabeth Winstead, Vanessa Ferlito, Jordan Ladd, Rose McGowan, Sydney Tamiia Poitier and Tracie Thomas. Some Tarantino regulars appear including the late Michael Parks and his son James, both of whom appeared in Kill Bill as the same characters they play here, Texas Rangers Earl and Edgar McGraw making for a satisfying little inclusion for Tarantino fans. The director’s friend and fellow director Eli Roth who would later appear in Inglorious Basterds has a small cameo here.

Now whilst Death Proof is inspired by and steals in bulk from the films to which it’s paying homage it also features considerable swathes of that trademark Tarantino dialogue delivered in extended scenes of conversation between the film’s two groups of female protagonists as well as the man who owns the killer stunt-car upon which the film is titled, Stuntman Mike. Mike is played by the legendary Kurt Russell and the seasoned actor imbues his character with equal measures of charm, sleaze and gleefully psychotic menace. Now whilst the long dialogue scenes in films such as Reservoir Dogs, Pulp Fiction and Jackie Brown are eminently rewatchable, the same cannot be said for Death Proof’s script, written by Tarantino himself. It’s in the first 40 minutes of Death Proof where the majority of the film’s issues lie. This first act consists almost exclusively of dialogue scenes but whereas the equivalent scenes in Pulp Fiction were engaging, funny and most importantly memorable, the same doesn’t apply here. If the dialogue had been written to be purposely bad then it would be easier to give it a pass but one gets the impression that this wasn’t the case as it isn’t the absurdly bad dialogue a B-movie homage such as this would require. The round table discussion in the diner between our second group of girls would seem almost purposely uninteresting if only it hadn’t dragged on for so long at which point you have to wonder whether Tarantino actually thinks this flat and meaningless dialogue is engaging. The opening tipping scene from Reservoir Dogs this most certainly isn’t.

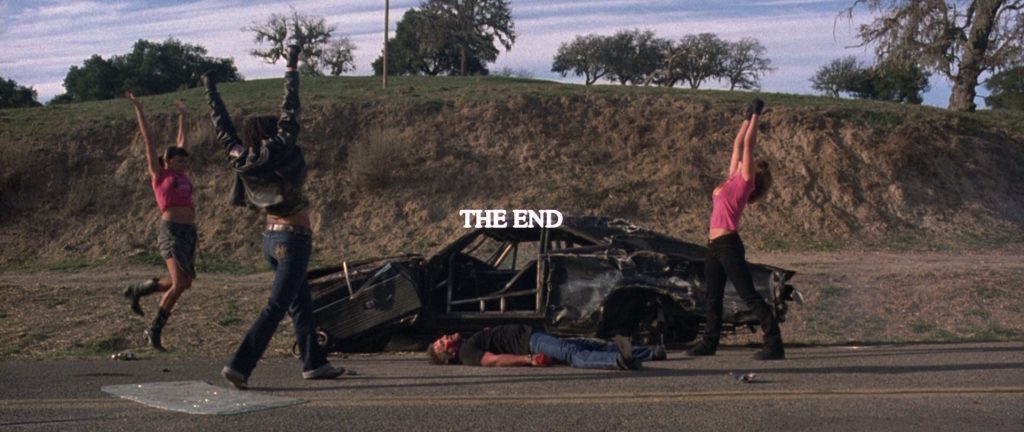

The reason there are two distinct groups of girls is that the first is stalked and then brutally killed in a staged car crash by Mike in his modified “Death Proof” stunt car. The scene is incredibly brutal and Tarantino uses multiple angles to show in exquisite detail the gory demise of the four victims. After a brief interlude where Ranger McGraw discusses his suspicions of Mike who survived the crash we are introduced to our second group of girls. As Mike first stalks them they seem just as vulnerable as the first group but these girls are in town to shoot a movie, one is an actress, the other a make-up artist and the remaining two are ass-kicking stunt women. When Mike finally engages them on the road in the last act the film kicks into high gear and doesn’t let up until the incredibly satisfying last shot. There’s nothing shoddy about the stunt work and Tarantino’s skill with the camera in this last act and coupled with Sally Menke’s sublime work in the editing suite, the film really is back-end loaded and builds to a satisfying revenge fuelled finale. The final scene with the girls laying into a badly injured but still standing Mike is a joy to behold and the perfectly abrupt ending has a cherry on top in the form of a hilarious post credits final killer blow to Mike from Rosario Dawson.

How do you fairly and objectively judge a film that’s purposely bad and intentionally amateurish against the remainder of Tarantino’s mostly incredible body of work where the opposite is the case? The other films in his oeuvre are made with a precision and attention to detail that the majority of other directors can only ever dream to attain. If Death Proof had been “so bad it’s good” then it could be seen as fully achieving its purpose and of the two films, Planet Terror seems to achieve this with far more success. That the second half feels more like the proper homage it’s trying to be after the laboriously slow first act does make up for things somewhat but aside from the first, shocking kills Mike makes, we have to wait far too long for the carnage to continue. The dialogue scenes take up the majority of the run time but simply aren’t enjoyable upon repeat viewings. Some bizarre aesthetic choices such as the perfectly clean print in the second half, make little sense and ultimately the film is nowhere near as knowingly bad as its director intends it to be. It’s as if Tarantino couldn’t make a film completely divorced from his own unique style and the schlocky B-movie he’s trying to make doesn’t befit the dialogue heavy style he’s so known for.

In a later interview Tarantino stated that, “Death Proof has to be the worst film I’ll make”. If read as intended with emphasis on the “has to be” part of that quote then it’s clear that he intended to make a bad film from the outset and when taken as part of the original two-film Grindhouse experiment, Death Proof kind of works. When taken as a standalone piece Death Proof has a lot to admire, especially in its nail-bitingly action packed last act but unfortunately the rest of the film is bogged down by a sedentary first 40 minutes and an equally uninteresting middle portion. Death Proof isn’t a bad film but ironically, and this is probably the only film to which this would ever apply, it would have been a far more satisfying experience if it actually was a genuinely bad film. Go figure.

Film ’89 Verdict – 6/10