RoboCop (1987) – Celebrating the 30th Anniversary of a Sci-Fi Classic.

In 1987 Orion Pictures produced a movie based on a script by Edward Neumeier and Michael Miner that had been bandied about and passed up on by several big name directors for some time before Orion’s Mike Medavoy passed it to Dutch Director Paul Verhoeven. Verhoeven upon seeing the script with its hokey title, RoboCop, balked at it and dismissed it as not being something he’d have any interest in directing. It was Verhoeven’s wife who read the script and saw the layers of satire and potential hidden allegories and urged him to read it. Verhoeven read the script and made an about turn and with a relatively modest budget of $13 million dollars would go on to make a film that not only firmly launched his career in Hollywood but would itself go on to be heralded as a classic of both 80’s and sci-fi cinema that acclaimed British director Ken Russell would famously describe as “The greatest science fiction film since Metropolis”.

I have a very deep, personal connection to RoboCop. It’s been my favourite movie since I first saw it in 1989 upon its rather belated UK home video release and it was also the first truly adult film I’d seen up until that point in my life. Its extreme violence shocked me and left an indelible mark. Its vile, memorable villains, breakneck pace and frenetic action were like nothing I’d ever seen before. I’ve revisited the film at various ages over the years and have regularly reappraised it, each time trying to gauge it objectively without letting the haze of nostalgia cloud my judgment. Whilst other movies I once loved in my youth now rate far less favourably with me when viewed as an adult, RoboCop is every bit as good now as it was all those years ago and in some respects even more so.

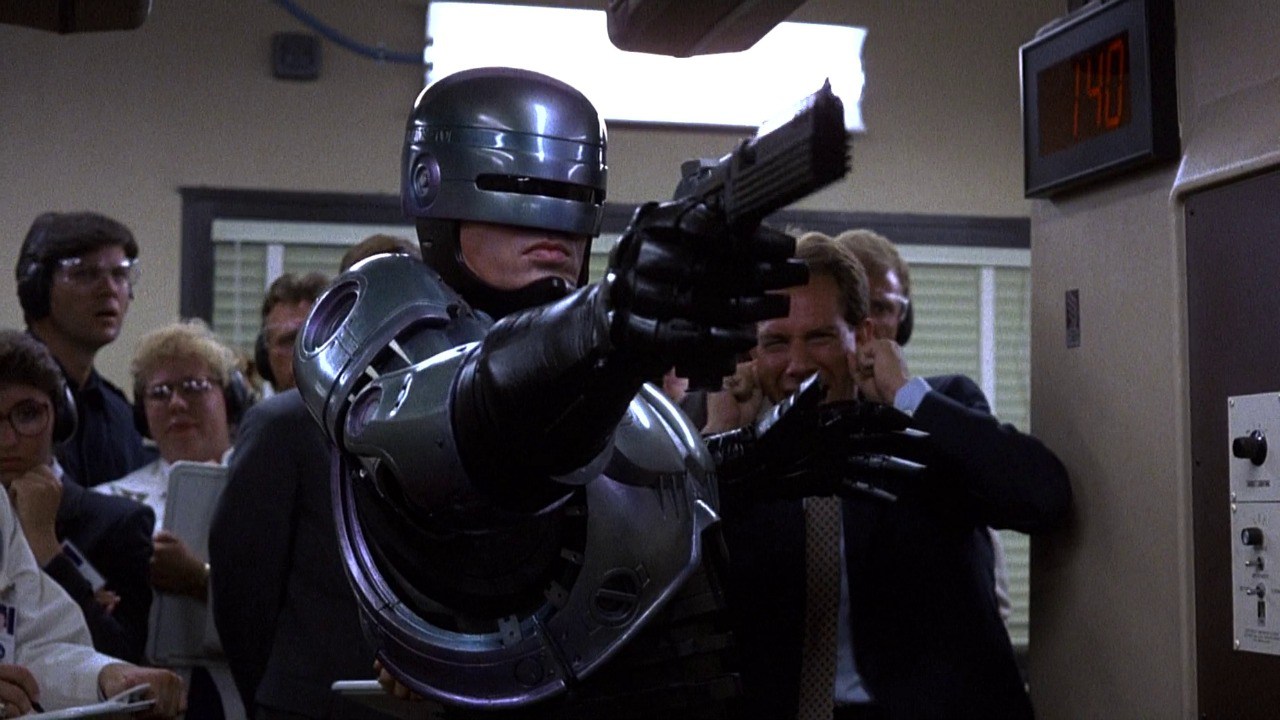

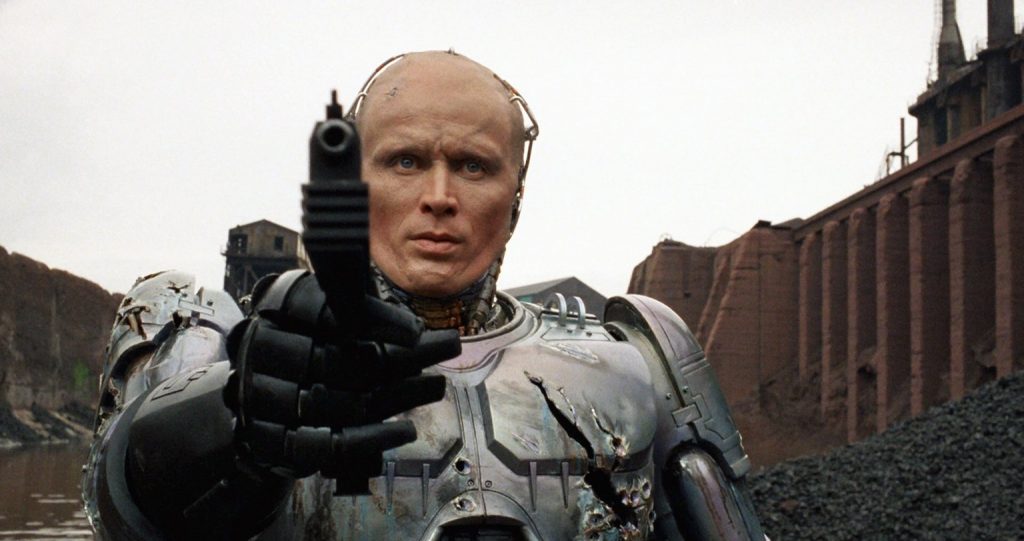

As an adult I now clearly see the deeper thematic elements which are at play such as the scathing commentary on 80’s corporate greed and Verhoeven’s Christ allegory told by way of Murphy’s own crucifixion at the hands of ruthless criminals and his subsequent resurrection at the hands of the no less ruthless Omni Consumer Products. The most powerful aspects of the movie are some of the more emotional elements, such as Murphy’s “I can feel them, but I can’t remember them” scene and Murphy returning to his abandoned family home, all played with perfectly balanced pathos by Peter Weller, who puts in a career best performance in a very difficult, unconventional acting role. What Weller does so well is subtly weave in aspects of Murphy’s regained humanity to the point where by the film’s final act his voice is far less robotic and closer to sounding almost human again.

The script and editing are second to none. RoboCop careens from one classic scene to another, yet is perfectly paced. There is no scene that feels surplus to requirements, no fat on the meat. Every scene propels the film’s narrative to its stunningly satisfying conclusion. The action scenes are flawlessly choreographed and edited with a consistent sense of geography that makes the action easy to follow. RoboCop’s tone is also very unique, due in no greater part to its director’s style. Verhoeven employs a hyper-realism, gun shot wounds look as horrific as they would in real life, the use of a non-scripted crash team to work on Murphy after he’s shot, all these things give a pleasing sheen of authenticity to the film that elevates it above its sci-fi genre trappings.

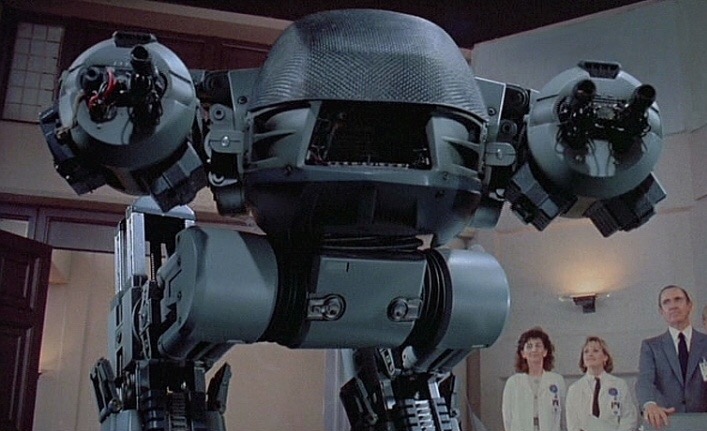

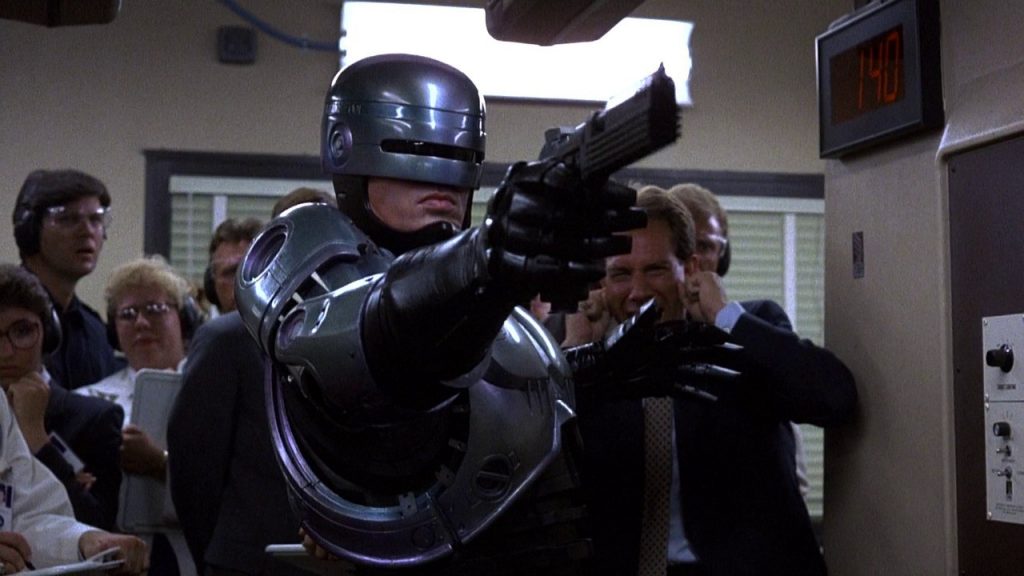

Special mention must go to the film’s technical aspects, namely the great production design and the RoboCop suit designed by Rob Bottin, who also did the film’s superb practical effects. The designs of RoboCop’s suit and Craig Davies’ imposing ED-209 have aged extremely well and have a timeless quality very much akin to the Stormtrooper designs in George Lucas’ Star Wars that have a similar timeless quality to their design aesthetic. And let’s not forget Basil Poledouris’ majestic score. The composer could have gone for a synthesised score typical of many 80’s action/sci-fi films but what he does here is take a percussive approach to much of the action and a more classical score elsewhere. Poledouris’ music perfectly complements the film and is equal parts rousing and mournfully melodic.

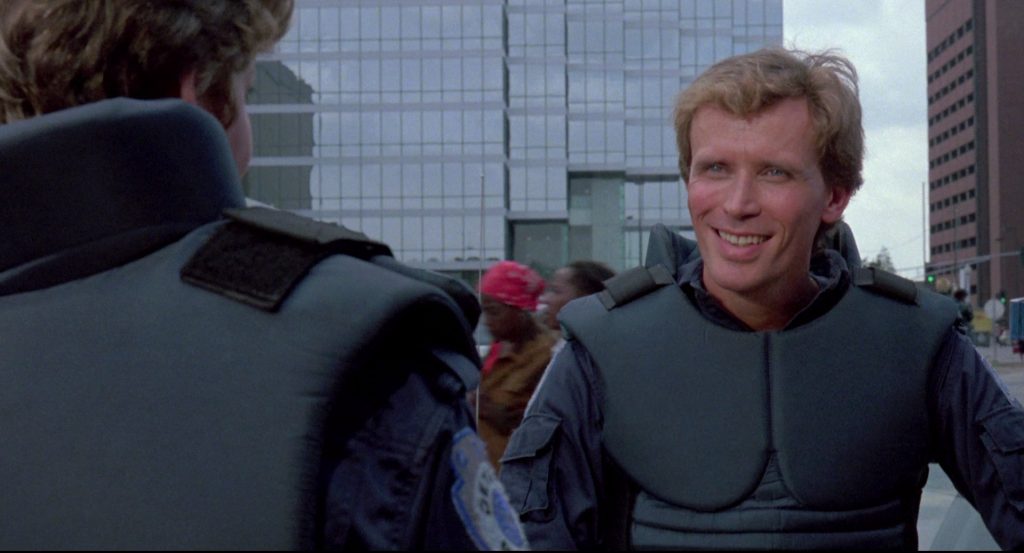

One of the things RoboCop is most famous for is the aforementioned violence, and indeed it is über violent, but the violence is an intrinsic factor that adds to the film’s unique quality and tone. Never before had such brutal, graphic, sadistic violence been portrayed in a major Hollywood movie. Again this is Verhoeven’s doing. Coming from Holland, where there was no equivalent of the MPAA, he was able to do as he wished as a film maker in his native country. He grew up during the Nazi occupation of Holland and violence was something he saw frequently and this shows in much of his work, and none more so than here where it is used to great effect to instill sympathy in Murphy’s character, who doesn’t get a great amount of screen time before being so brutally killed. The brutality also paints the film’s future Detroit as a cold, merciless place yet the violence never feels excessive when seen in context of the movie, but it is certainly not a film for the faint hearted. Whilst on the subject, special mention must go to Kurtwood Smith’s exceptionally vile and sadistic Clarence Boddiker, easily a contender for Best Movie Villain Ever. If Smith’s performance wasn’t enough we also have Ronny Cox playing against type as the equally villainous Dick Jones. Neither character seems cartoonish or overblown but both are utterly insipid individuals and incredibly effective in driving the revenge aspect that for me is the core of RoboCop’s layered narrative.

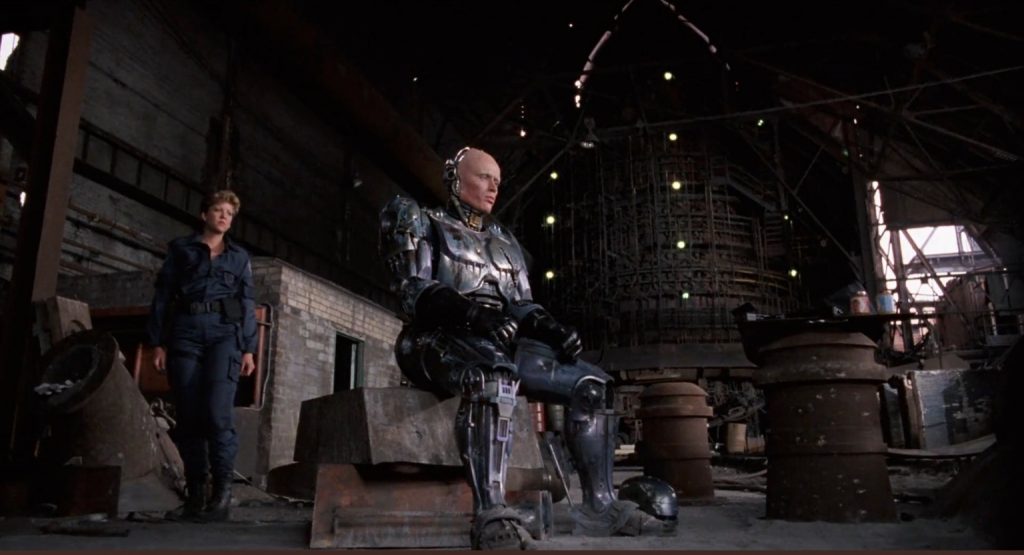

RoboCop is very much a product of the 80’s, particularly Reagan’s 80’s America and this is in no way to its detriment. Indeed as the recent neutered, generic, typically modern Hollywood remake shows, they’d struggle to get any big studio to make a film this visceral these days. It even manages to be strangely prophetic – the real city of Detroit recently filing bankruptcy and Downtown Dallas, Houston, where the bulk of RoboCop was filmed, now more than ever looks like the Old Detroit depicted in the film. RoboCop has in its arsenal, amongst other things, an incredible, almost mythical third act which is more Western than Sci-Fi. The use of a dilapidated Pittsburgh steel mill for the finale has old technology meeting new and is as perfect a use of a real world location as I’ve seen in a film. From the point where Lewis goes back to the Steel Mill to bring Murphy supplies the film starts to peak and doesn’t let up until the incredibly satisfying final scene, which scored off the chart with test audiences causing the originally planned final Media Break ending to be dropped leaving the “Nice shooting son, what’s your name?” ending we have now.

RoboCop is a movie that has it all, a great script with endlessly quotable dialogue, great performances across the board, great effects that service the film instead of acting as a distraction, a superb score, flawless editing, a classic revenge theme, The Greatest Film Location Ever™ (The Old Steel Mill), the list goes on. I’ll finish with this, don’t look beyond the original RoboCop as its greatness is only sullied by the poor sequels and dire TV series that followed. Instead see it as it should have remained, an undiluted classic, a masterpiece of modern film making with wit, brutality but also a very clearly defined soul. Nice shooting indeed!

Film ’89 Verdict – 10/10